Gasification: Gasification is a thermochemical process that converts carbonaceous materials, such as biomass, coal, or organic waste, into synthesis gas (syngas) consisting mainly of hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), and methane (CH4). The process occurs in a gasifier, where the feedstock is subjected to high temperatures (>700°C) and controlled amounts of oxygen or steam in a low-oxygen environment. Gasification involves several key reactions, including pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction, leading to the production of a clean and versatile fuel gas that can be used for power generation, chemical synthesis, hydrogen production, and other industrial applications. Gasification offers advantages such as high energy efficiency, low emissions, and flexibility in feedstock selection, making it a promising technology for sustainable energy production and waste management.

Gasification

- Pyrolysis: Pyrolysis is a thermal decomposition process that converts biomass or organic materials into biochar, bio-oil, and syngas in the absence of oxygen or with limited oxygen supply. During pyrolysis, the feedstock is heated to temperatures typically ranging from 300°C to 800°C, causing the breakdown of complex organic molecules into simpler compounds. The pyrolysis products can vary depending on the temperature, heating rate, and residence time, with biochar being the solid residue, bio-oil being the liquid fraction, and syngas consisting of gaseous components such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane. Pyrolysis offers several advantages, including the production of biochar for soil amendment, bio-oil for biofuel production, and syngas for energy generation, making it a versatile technology for biomass utilization and waste valorization.

- Combustion: Combustion is a chemical reaction in which a fuel reacts with oxygen to produce heat, light, and combustion products such as carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor (H2O), and other gases. In the context of thermal conversion, combustion refers to the controlled burning of biomass, coal, or waste materials to generate heat or energy. Combustion processes typically occur in boilers, furnaces, or power plants, where the fuel is burned in the presence of air or oxygen to produce steam for electricity generation, heat for industrial processes, or hot water for heating applications. Combustion technologies range from traditional stoker-fired boilers to advanced fluidized bed combustors and gasification-combustion systems, offering efficient and reliable solutions for energy production with varying fuel types and quality.

- Incineration: Incineration is a thermal treatment process that involves the combustion of solid, liquid, or gaseous waste materials to reduce their volume, destroy hazardous components, and recover energy. In incineration plants, waste materials are combusted at high temperatures (>800°C) in specially designed furnaces or kilns equipped with pollution control devices to minimize emissions of pollutants such as particulate matter, dioxins, and heavy metals. The heat generated during incineration can be recovered in the form of steam or hot gases for electricity generation, district heating, or industrial processes, providing a sustainable and environmentally sound method for waste management and resource recovery.

- Torrefaction: Torrefaction is a mild pyrolysis process that involves the thermal treatment of biomass in the absence of oxygen at temperatures typically ranging from 200°C to 300°C. During torrefaction, biomass undergoes partial decomposition and removal of volatile compounds, resulting in a dry, brittle, and energy-dense solid fuel known as torrefied biomass or biocoal. Torrefied biomass exhibits improved properties such as higher energy density, lower moisture content, and enhanced grindability and storability compared to raw biomass, making it suitable for combustion, gasification, or co-firing with coal in power plants. Torrefaction offers benefits such as reduced transportation costs, improved biomass logistics, and increased utilization of renewable biomass resources for energy production.

- Carbonization: Carbonization is a thermal conversion process that transforms organic materials such as wood, peat, or agricultural residues into carbon-rich char or charcoal through the elimination of volatile components. The process occurs at temperatures typically ranging from 300°C to 700°C in the absence of oxygen or with limited oxygen supply, preventing complete combustion and promoting the formation of carbonaceous residues. Carbonization can be achieved through various methods, including traditional kiln carbonization, retort carbonization, or modern pyrolysis technologies. The resulting charcoal can be used as a solid fuel for cooking, heating, or metallurgical processes, as a soil amendment for agriculture, or as a precursor for activated carbon production, providing valuable products and environmental benefits through the conversion of biomass into stable carbonaceous materials.

- Biomass-to-energy: Biomass-to-energy refers to the process of converting biomass feedstocks such as wood, agricultural residues, energy crops, or organic waste into heat, electricity, or biofuels through thermal conversion technologies such as combustion, gasification, or pyrolysis. Biomass-to-energy systems utilize the energy stored in biomass materials to generate power or heat for industrial, commercial, or residential applications, offering renewable and sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels. Biomass-to-energy technologies play a crucial role in decentralized energy production, rural development, and climate change mitigation by harnessing the carbon-neutral energy potential of biomass resources while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on non-renewable energy sources.

- Waste-to-energy: Waste-to-energy involves the conversion of municipal solid waste (MSW), industrial waste, or other waste materials into heat, electricity, or fuels through thermal conversion processes such as incineration, gasification, or pyrolysis. Waste-to-energy facilities provide an environmentally sustainable solution for waste management by reducing the volume of waste, recovering energy from organic materials, and minimizing the environmental impact of landfills. Waste-to-energy technologies contribute to resource recovery, energy production, and renewable energy generation while addressing waste disposal challenges and promoting circular economy principles through the utilization of waste as a valuable resource for energy production and resource conservation.

- Biochar production: Biochar production involves the thermal conversion of biomass feedstocks into a stable carbonaceous material known as biochar through processes such as pyrolysis or carbonization. Biochar is a porous, carbon-rich material that retains nutrients, enhances soil fertility, and improves soil structure and water retention when applied to agricultural soils. Biochar production offers several benefits, including carbon sequestration, soil carbon storage, and climate change mitigation, by converting biomass into a stable form of organic carbon that can persist in the soil for centuries. Biochar also provides opportunities for sustainable agriculture, bioenergy production, and waste management through the utilization of biomass resources for soil improvement and environmental remediation.

- Thermal depolymerization: Thermal depolymerization is a thermochemical process that converts organic waste materials such as plastics, rubber, or organic sludge into liquid hydrocarbons, gases, and solid residues through the application of heat and pressure in the presence of water or steam. During thermal depolymerization, complex organic polymers are broken down into smaller hydrocarbon molecules, which can be further refined into fuels, chemicals, or feedstocks for various industrial applications. Thermal depolymerization offers a promising solution for waste valorization and resource recovery by converting non-recyclable waste materials into

Gasification:

Gasification is a thermochemical process that transforms carbonaceous materials into a mixture of gases known as synthesis gas (syngas) by subjecting them to high temperatures and controlled amounts of oxygen or steam in a low-oxygen environment. This process typically occurs in a gasifier, where solid, liquid, or gaseous feedstocks such as biomass, coal, or waste materials are converted into a combustible gas containing hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, and other hydrocarbons.

The gasification process involves several key steps. Firstly, the feedstock is introduced into the gasifier, where it undergoes drying and devolatilization, releasing volatile components such as water, tar, and organic compounds. These volatiles then undergo further decomposition through pyrolysis, resulting in the formation of char, which serves as a porous matrix for subsequent gasification reactions.

Next, the char undergoes gasification reactions, where it reacts with oxygen or steam to produce syngas. Depending on the gasification conditions, various gasification agents can be employed, including air, oxygen, steam, or a combination thereof. The choice of gasification agent influences the composition and properties of the resulting syngas, with oxygen-blown gasification typically yielding higher hydrogen content, while steam-blown gasification favors higher carbon monoxide production.

Gasification offers several advantages over traditional combustion processes. Firstly, it allows for the utilization of a wide range of feedstocks, including low-quality or waste materials that are unsuitable for direct combustion. Additionally, gasification facilitates the production of a clean and versatile fuel gas that can be used for power generation, heating, or as a feedstock for chemical synthesis processes. Furthermore, gasification can be integrated with other energy conversion technologies such as combined heat and power (CHP) systems or fuel cells to achieve higher overall efficiency and energy utilization.

Overall, gasification represents a promising pathway towards sustainable energy production and waste management, offering a flexible and efficient means of converting diverse feedstocks into valuable energy products while minimizing environmental impact and resource depletion. As research and development efforts continue to advance gasification technologies, its potential applications in both stationary and mobile energy systems are expected to expand, contributing to the transition towards a more sustainable and resilient energy future.

Pyrolysis:

Pyrolysis is a thermochemical process that decomposes organic materials in the absence of oxygen or with limited oxygen supply, resulting in the production of biochar, bio-oil, and syngas. This process involves heating the biomass feedstock to elevated temperatures (typically between 300°C and 800°C), causing it to undergo thermal degradation and break down into volatile gases, liquids, and solid char.

During pyrolysis, the biomass feedstock undergoes several stages of decomposition. Initially, the moisture content of the biomass is removed through drying, followed by the release of volatile compounds such as organic acids, aldehydes, and ketones during the pyrolysis reactions. These volatile components are then condensed to form bio-oil, a dark, viscous liquid with energy content comparable to conventional petroleum fuels.

Simultaneously, solid carbonaceous residues, known as biochar or charcoal, are formed as the non-volatile fraction of the biomass undergoes carbonization. Biochar is a stable, carbon-rich material that retains the skeletal structure of the original biomass and contains high levels of fixed carbon, making it suitable for applications such as soil amendment, carbon sequestration, and water filtration.

In addition to biochar and bio-oil, pyrolysis also produces a mixture of gases known as syngas, which typically consists of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, and other hydrocarbons. Syngas can be utilized as a renewable fuel for power generation, heating, or as a feedstock for chemical synthesis processes, offering versatility and flexibility in energy applications.

Pyrolysis technologies can be classified based on the heating rate, residence time, and operating conditions. Fast pyrolysis processes, characterized by rapid heating rates and short residence times, favor the production of bio-oil, while slow pyrolysis processes, with slower heating rates and longer residence times, result in higher biochar yields. Intermediate pyrolysis processes offer a compromise between biochar and bio-oil production, providing a balanced output of both products.

Overall, pyrolysis represents a promising pathway for converting biomass into valuable energy products and bio-based materials, offering environmental benefits such as carbon sequestration, waste reduction, and renewable energy production. As research and development efforts continue to advance, pyrolysis technologies are expected to play an increasingly important role in the transition towards a sustainable and low-carbon economy.

Combustion:

Combustion is a chemical reaction between a fuel and an oxidizing agent, typically oxygen, that results in the rapid release of heat and light energy. In the context of thermal conversion, combustion refers to the controlled burning of solid, liquid, or gaseous fuels to generate heat or produce power.

The combustion process involves several key steps. Firstly, the fuel and oxidizer are brought into contact and mixed to ensure efficient combustion. In the case of solid fuels such as biomass or coal, they are typically pulverized or shredded to increase the surface area available for combustion. Liquid fuels such as oil or ethanol are atomized into fine droplets, while gaseous fuels such as natural gas or hydrogen are mixed with air or oxygen in the proper stoichiometric ratio.

Once the fuel and oxidizer are mixed, they are ignited, initiating the combustion reaction. During combustion, the fuel molecules break apart and react with oxygen molecules to form carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor (H2O), and other combustion products such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO2), depending on the fuel composition and combustion conditions.

The heat released during combustion raises the temperature of the surrounding environment, which can be utilized for various applications such as space heating, water heating, steam generation, or electricity production. Combustion processes can be classified based on the type of fuel used (solid, liquid, or gaseous), the combustion technology employed (e.g., fluidized bed combustion, pulverized coal combustion), and the combustion system’s design and operating parameters.

Combustion technologies have been widely used for centuries to meet human energy needs, from heating and cooking to industrial processes and power generation. While combustion provides a convenient and reliable source of energy, it also produces emissions such as CO2, NOx, SO2, and particulate matter, which can have negative environmental and health impacts if not properly controlled. As a result, efforts are underway to develop cleaner and more efficient combustion technologies, such as advanced flue gas cleaning systems, low-emission burners, and integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) plants, to minimize environmental pollution and mitigate climate change.

Incineration:

Incineration is a thermal treatment process that involves the controlled combustion of waste materials to convert them into ash, flue gases, and heat. This process is typically carried out in specially designed facilities called incinerators, which are equipped with combustion chambers, flue gas treatment systems, and energy recovery units.

The incineration process begins with the collection and preparation of waste materials, which may include municipal solid waste (MSW), hazardous waste, medical waste, or industrial waste. The waste is then transported to the incineration facility, where it undergoes sorting and shredding to remove contaminants and optimize combustion efficiency.

Once prepared, the waste is fed into the combustion chamber of the incinerator, where it is burned at high temperatures (typically between 800°C and 1,200°C) in the presence of excess air or oxygen. During combustion, organic materials in the waste are oxidized to carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapor (H2O), while inorganic materials are converted into ash.

The heat generated during incineration is recovered through heat exchangers or boiler systems, where it is used to produce steam for electricity generation, district heating, or industrial processes. This process, known as waste-to-energy (WTE) or energy recovery, helps offset the energy consumption of the incineration facility and provides a renewable energy source.

In addition to energy recovery, incineration also serves to reduce the volume of waste and destroy hazardous components such as pathogens, organic pollutants, and toxic chemicals. Modern incineration facilities are equipped with advanced pollution control technologies, such as bag filters, electrostatic precipitators, and scrubbers, to capture and neutralize harmful emissions such as particulate matter, heavy metals, dioxins, and furans.

While incineration offers several benefits, including waste volume reduction, energy recovery, and pollution control, it also raises concerns about air emissions, ash disposal, and public health impacts. To address these concerns, stringent regulations and emission standards have been implemented to ensure the safe and environmentally sound operation of incineration facilities. Additionally, efforts are underway to promote waste minimization, recycling, and alternative waste treatment technologies to complement and reduce the reliance on incineration for waste management.

Gas Cleaning:

Gas cleaning is a crucial step in thermal conversion processes, particularly those involving combustion, gasification, and pyrolysis, where the generated gases may contain impurities, pollutants, and particulate matter that need to be removed before discharge or utilization. Gas cleaning technologies aim to minimize emissions, improve air quality, and ensure compliance with environmental regulations.

Several methods are employed for gas cleaning, depending on the type and concentration of contaminants present in the gas stream. Some of the common gas cleaning techniques include:

- Particulate Removal: Particulate matter, such as ash, soot, and dust, can be removed from the gas stream using devices like electrostatic precipitators, fabric filters (baghouses), cyclones, or wet scrubbers. These devices use different mechanisms, such as electrostatic forces, filtration, centrifugal force, or wet scrubbing, to capture and remove particulates from the gas stream.

- Acid Gas Removal: Acid gases, including sulfur dioxide (SO2), hydrogen chloride (HCl), and hydrogen fluoride (HF), can be removed from the gas stream through processes such as wet scrubbing, dry scrubbing, or chemical absorption. Wet scrubbers use a liquid absorbent (e.g., water, lime slurry) to chemically react with and remove acid gases, while dry scrubbers employ solid sorbents (e.g., lime, limestone) to adsorb or react with the acid gases.

- Mercury Removal: Mercury emissions from thermal conversion processes can be controlled using specialized sorbent injection systems or activated carbon injection (ACI) systems. These systems inject sorbents or activated carbon into the gas stream, where they adsorb mercury vapor and remove it from the gas phase.

- Particulate Matter Control: Advanced technologies such as catalytic converters and ceramic filters can be used to control particulate emissions from thermal conversion processes. Catalytic converters employ catalysts to promote the oxidation of organic pollutants, while ceramic filters utilize porous ceramic materials to capture and remove particulate matter from the gas stream.

- NOx Reduction: Nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions can be reduced using selective catalytic reduction (SCR) or selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) systems. SCR systems use a catalyst to convert NOx into nitrogen (N2) and water vapor (H2O) using ammonia as a reducing agent, while SNCR systems inject urea or ammonia directly into the flue gas stream to chemically reduce NOx emissions.

Overall, gas cleaning technologies play a crucial role in mitigating the environmental impact of thermal conversion processes by removing harmful pollutants and ensuring compliance with regulatory standards. Continued research and development efforts are focused on improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of gas cleaning technologies to address emerging environmental challenges and promote sustainable energy production.

Catalytic Conversion:

Catalytic conversion is a chemical process that involves the use of catalysts to facilitate the transformation of reactants into desired products at lower temperatures and pressures compared to traditional thermal conversion methods. This process is widely used in various industries, including petroleum refining, chemical synthesis, and environmental remediation, to produce high-value products, reduce energy consumption, and minimize environmental impact.

In catalytic conversion, a catalyst is a substance that accelerates the rate of chemical reactions by providing an alternative reaction pathway with lower activation energy. Catalysts do not undergo permanent chemical changes during the reaction and can be used repeatedly, making them highly efficient and cost-effective for large-scale industrial processes.

There are two main types of catalytic conversion processes:

- Heterogeneous Catalysis: In heterogeneous catalysis, the catalyst exists in a different phase from the reactants and products. Typically, solid catalysts are used, and the reactants are in the gas or liquid phase. The catalytic reaction occurs on the surface of the catalyst, where the reactant molecules adsorb onto active sites, undergo chemical transformations, and desorb as products. Examples of heterogeneous catalytic processes include catalytic cracking in petroleum refining, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of nitrogen oxides (NOx) in exhaust gases, and Fischer-Tropsch synthesis for producing synthetic fuels from syngas.

- Homogeneous Catalysis: In homogeneous catalysis, both the catalyst and the reactants are in the same phase, usually in solution. Homogeneous catalysis often involves transition metal complexes or organometallic compounds that can undergo reversible coordination or redox reactions with the reactants. Homogeneous catalytic processes are particularly useful for organic synthesis, where precise control over reaction conditions and selectivity is desired. Examples of homogeneous catalytic reactions include hydrogenation, oxidation, and hydroformylation reactions.

Catalytic conversion offers several advantages over traditional thermal conversion methods. Firstly, catalytic processes operate under milder conditions, resulting in lower energy consumption, reduced equipment corrosion, and improved selectivity towards desired products. Additionally, catalytic conversion enables the utilization of renewable feedstocks, such as biomass-derived sugars or oils, for the production of biofuels, chemicals, and materials, contributing to sustainability and resource conservation efforts.

Overall, catalytic conversion plays a critical role in modern industrial processes by enabling efficient and selective chemical transformations, driving innovation in energy production, environmental protection, and sustainable development. Continued research and development efforts are focused on designing novel catalysts, optimizing reaction conditions, and scaling up catalytic processes to meet the growing demand for cleaner, more efficient, and sustainable technologies.

Carbonization:

Carbonization is a thermochemical process that involves the conversion of organic materials into carbon-rich char or carbonaceous residue through heating in the absence of oxygen or with limited oxygen supply. This process is commonly used to produce charcoal from biomass feedstocks such as wood, agricultural residues, or organic waste.

During carbonization, the organic material is subjected to elevated temperatures (typically between 300°C and 700°C) in a low-oxygen environment, such as a kiln, retort, or pyrolysis reactor. As the temperature increases, volatile components such as water, tar, and other organic compounds are driven off, leaving behind a solid residue composed primarily of carbon.

The carbonization process can be divided into several stages:

- Drying: In the initial stage, moisture present in the biomass is evaporated and removed from the material. This helps reduce energy consumption during subsequent heating and prevents steam explosions or excessive pressure buildup within the carbonization vessel.

- Pyrolysis: As the temperature continues to rise, the biomass undergoes pyrolysis, a thermal decomposition process where organic compounds break down into volatile gases and liquid products. This stage is characterized by the release of tar, methane, hydrogen, and other volatile hydrocarbons, which are typically collected and used as fuel or chemical feedstock.

- Carbonization: In the final stage, the remaining solid residue is subjected to further heating, causing it to undergo carbonization. During this process, the organic material decomposes further, with the formation of char or carbonaceous residue rich in fixed carbon. The carbonization temperature and residence time influence the properties of the resulting charcoal, including its carbon content, porosity, and mechanical strength.

Carbonization is a key step in the production of charcoal, a valuable energy source and raw material used in various applications, including metallurgy, cooking, and filtration. Charcoal is prized for its high carbon content, low ash content, and long burning time, making it an efficient and versatile fuel for heating and cooking in both domestic and industrial settings.

In addition to charcoal production, carbonization also plays a role in the production of activated carbon, a highly porous form of carbon used for water purification, air filtration, and environmental remediation. Activated carbon is produced by further processing charcoal through physical or chemical activation methods, which increase its surface area and adsorption capacity.

Overall, carbonization is a fundamental process in biomass conversion, enabling the production of valuable carbonaceous materials for energy, industry, and environmental applications. Continued research and development efforts are focused on optimizing carbonization processes, improving charcoal quality, and exploring novel applications for carbonaceous materials in emerging technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and renewable energy storage.

Gasification:

Gasification is a thermochemical process that converts carbonaceous feedstocks, such as coal, biomass, or municipal solid waste, into a synthesis gas (syngas) containing hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, and other gaseous components. This process occurs in a controlled environment with a limited supply of oxygen or steam, typically at elevated temperatures ranging from 600°C to 1,500°C.

The gasification process involves several key steps:

- Feedstock Preparation: The carbonaceous feedstock, such as coal, wood chips, or agricultural residues, is first prepared by drying and grinding to a suitable particle size. This increases the surface area and facilitates the conversion process.

- Feedstock Gasification: The prepared feedstock is then fed into a gasifier, where it undergoes thermochemical reactions in the presence of a gasification agent, typically steam, oxygen, or a combination of both. The feedstock reacts with the gasification agent at high temperatures, leading to the production of syngas.

- Syngas Generation: The gasification reactions produce a mixture of gases, including hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and other trace gases. The composition of the syngas depends on factors such as the feedstock type, gasification conditions, and the choice of gasification agent.

- Tar and Particulate Removal: Gasification of biomass feedstocks can produce tar and particulate matter, which need to be removed to prevent equipment fouling and ensure downstream process efficiency. Various tar removal technologies, such as scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters, are employed to clean the syngas before it is used or further processed.

- Syngas Utilization: The syngas produced during gasification can be utilized for various applications, including power generation, heat production, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis. Syngas can be burned directly in gas turbines, boilers, or engines to generate electricity or heat. Alternatively, it can be further processed to separate and purify individual gas components for use in chemical processes or as fuel for hydrogen fuel cells.

Gasification offers several advantages over traditional combustion processes, including higher energy efficiency, lower emissions, and greater fuel flexibility. It enables the conversion of a wide range of feedstocks, including low-quality coal, biomass residues, and waste materials, into a clean and versatile energy carrier. Gasification also facilitates carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies by producing a concentrated stream of CO2, which can be captured and sequestered to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

Overall, gasification represents a promising pathway for sustainable energy production and resource utilization, offering a versatile and efficient technology for converting diverse feedstocks into valuable fuels, chemicals, and energy products. Continued research and development efforts are focused on improving gasification processes, increasing process efficiency, and expanding the range of feedstocks and applications for gasification technology.

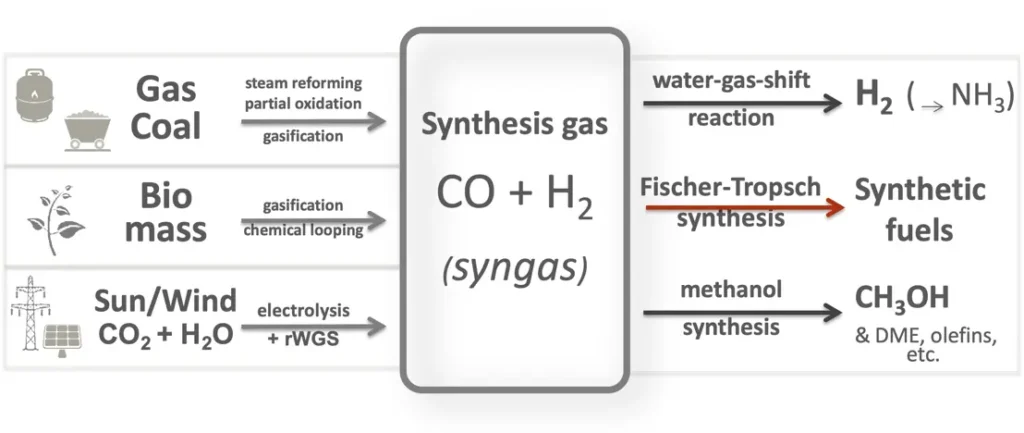

Syngas:

Syngas, short for synthesis gas, is a mixture of gases primarily composed of hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO), along with lesser amounts of methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and other trace gases. It is produced through the gasification of carbonaceous feedstocks such as coal, biomass, or municipal solid waste in a controlled environment with a limited supply of oxygen or steam.

The composition of syngas depends on several factors, including the type of feedstock, gasification conditions (temperature, pressure, residence time), and the choice of gasification agent (oxygen, steam, air). Typically, syngas has a H2/CO ratio ranging from 1:1 to 3:1, which can be adjusted depending on the desired end-use applications.

Syngas is a versatile energy carrier with a wide range of applications across various industries:

- Power Generation: Syngas can be burned directly in gas turbines, boilers, or internal combustion engines to generate electricity or heat. Combined cycle power plants utilize syngas as a fuel source to maximize energy efficiency by capturing waste heat for additional power generation.

- Hydrogen Production: Syngas can be used as a precursor for hydrogen production through a process called water-gas shift reaction. In this reaction, CO reacts with steam (H2O) to produce CO2 and H2. The resulting hydrogen-rich syngas can be further purified to produce high-purity hydrogen for fuel cells, ammonia production, or industrial processes.

- Chemical Synthesis: Syngas serves as a feedstock for the production of a wide range of chemicals and fuels through catalytic processes such as Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, methanol synthesis, and hydrocarbon synthesis. These processes utilize the H2 and CO present in syngas to produce valuable products such as methanol, ammonia, synthetic fuels, and olefins.

- Biorefining: Syngas produced from biomass gasification can be integrated into biorefinery processes for the production of biofuels and biochemicals. Biomass-derived syngas can be converted into biofuels such as ethanol, biodiesel, or synthetic diesel through thermochemical or biochemical conversion pathways.

- Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU): Syngas can be used as a feedstock for carbon capture and utilization (CCU) technologies to produce value-added products while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. CO2 captured from syngas can be utilized for the production of chemicals, polymers, or construction materials through processes such as carbonation or mineralization.

Syngas offers several advantages as an energy carrier, including its flexibility, abundance of feedstock sources, and potential for carbon capture and utilization. However, challenges such as gas cleanup, gas quality control, and process efficiency optimization need to be addressed to fully realize the potential of syngas for sustainable energy production and resource utilization. Continued research and development efforts are focused on advancing gasification technologies, improving syngas conversion processes, and exploring novel applications for syngas in the transition towards a low-carbon economy.

Biomass Gasification:

Biomass gasification is a thermochemical process that converts biomass feedstocks into a combustible gas mixture called syngas. This process occurs in a gasifier, where biomass materials such as wood chips, agricultural residues, or organic waste are subjected to high temperatures and a controlled supply of oxygen, steam, or a combination of both. The gasification reactions produce a synthesis gas (syngas) containing hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, and other gaseous components, along with tar, char, and ash residues.

The biomass gasification process involves several key steps:

- Feedstock Preparation: Biomass feedstocks are first prepared by drying and grinding to a suitable particle size. This increases the surface area and facilitates the conversion process in the gasifier.

- Gasification Reactions: The prepared biomass feedstock is fed into the gasifier, where it undergoes thermochemical reactions in a low-oxygen environment at temperatures typically ranging from 700°C to 1,200°C. The biomass reacts with the gasification agent (oxygen, steam, or a combination) to produce syngas through a series of endothermic and exothermic reactions, including pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction.

- Syngas Cleanup: The raw syngas produced from biomass gasification contains impurities such as tar, particulate matter, and contaminants that need to be removed to meet quality specifications for downstream applications. Various gas cleanup technologies, including cyclones, scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters, are employed to remove impurities and improve syngas quality.

- Syngas Utilization: The cleaned syngas can be utilized for various energy and chemical applications, including power generation, heat production, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis. Syngas can be burned directly in gas turbines, boilers, or engines to generate electricity or heat. Alternatively, it can be further processed to separate and purify individual gas components for use in chemical processes or as fuel for hydrogen fuel cells.

Biomass gasification offers several advantages over traditional combustion-based energy systems, including higher energy efficiency, lower emissions, and greater fuel flexibility. It enables the conversion of a wide range of biomass feedstocks, including agricultural residues, forestry waste, energy crops, and organic waste materials, into a clean and versatile energy carrier. Biomass gasification also promotes resource conservation and environmental sustainability by utilizing renewable feedstocks and reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Overall, biomass gasification represents a promising technology for sustainable energy production and waste management, offering a renewable and environmentally friendly pathway for generating heat, power, and fuels from biomass resources. Continued research and development efforts are focused on improving gasification processes, increasing process efficiency, and expanding the range of biomass feedstocks and applications for biomass gasification technology.

Gasifier Design:

Gasifier design refers to the engineering and configuration of gasification systems used to convert carbonaceous feedstocks into synthesis gas (syngas) through thermochemical processes. Gasifier design plays a crucial role in determining the efficiency, performance, and reliability of gasification systems for various applications, including power generation, heat production, and chemical synthesis.

Key aspects of gasifier design include:

- Reactor Configuration: Gasifiers can be classified based on their reactor configuration, including fixed-bed, fluidized-bed, entrained-flow, and downdraft gasifiers. Each type has unique characteristics and operating conditions that influence gasification performance, syngas quality, and process efficiency.

- Feedstock Handling: Gasifier design must accommodate the characteristics of the feedstock, including particle size, moisture content, and ash composition. Systems for feedstock preparation, handling, and feeding into the gasifier are designed to ensure uniform fuel distribution, efficient heating, and optimal gasification performance.

- Gasification Agent: Gasifiers can use various gasification agents, including air, oxygen, steam, or a combination, to facilitate the thermochemical reactions during gasification. The choice of gasification agent influences syngas composition, gasification efficiency, and process economics.

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Gasifier design includes provisions for controlling operating parameters such as temperature, pressure, and residence time to optimize gasification performance and syngas quality. Temperature control is critical to ensure proper biomass conversion, minimize tar formation, and maximize gasification efficiency.

- Syngas Cleanup: Gasifier design may incorporate syngas cleanup systems to remove impurities such as tar, particulate matter, and contaminants from the raw syngas. Various cleanup technologies, including cyclones, scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters, are integrated into the gasification system to improve syngas quality and meet downstream requirements.

- Heat Management: Gasifier design includes provisions for managing heat transfer within the system to maintain optimal operating temperatures and thermal efficiency. Heat recovery systems may be incorporated to capture and utilize waste heat for preheating feedstock, generating steam, or providing process heat for other applications.

- Safety and Reliability: Gasifier design prioritizes safety and reliability by incorporating features such as gas leak detection, pressure relief systems, and emergency shutdown mechanisms to prevent accidents and ensure system integrity during operation.

Gasifier design is a multidisciplinary endeavor that integrates principles of chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, materials science, and process control. Advanced computational modeling and simulation techniques are employed to optimize gasifier design, predict performance, and guide system improvements.

Overall, effective gasifier design is essential for the successful deployment of gasification technology in diverse applications, offering sustainable solutions for energy production, waste management, and resource utilization. Continued research and development efforts are focused on advancing gasifier design methodologies, enhancing system performance, and expanding the range of feedstocks and applications for gasification technology.

Biomass Conversion:

Biomass conversion refers to the process of transforming biomass feedstocks into useful energy carriers, chemicals, materials, and products through various thermochemical, biochemical, and physicochemical processes. Biomass, derived from organic sources such as plants, forestry residues, agricultural crops, and organic waste, represents a renewable and abundant resource that can be utilized to meet energy needs and reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

There are several pathways for biomass conversion, each with its own advantages, limitations, and applications:

- Thermochemical Conversion:

- Gasification: Biomass gasification converts solid biomass into synthesis gas (syngas) through thermochemical reactions in a controlled environment with limited oxygen or steam. Syngas can be used for power generation, heat production, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis.

- Pyrolysis: Biomass pyrolysis involves heating biomass in the absence of oxygen to produce bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. Bio-oil can be upgraded to produce transportation fuels, while biochar can be used as a soil amendment or carbon sequestration agent.

- Combustion: Biomass combustion involves burning biomass directly to produce heat, steam, or electricity. It is commonly used in residential, commercial, and industrial heating applications, as well as in biomass-fired power plants.

- Biochemical Conversion:

- Anaerobic Digestion: Biomass can undergo anaerobic digestion, where microorganisms break down organic matter in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas (a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide) and digestate (a nutrient-rich fertilizer).

- Fermentation: Biomass fermentation utilizes microorganisms to convert sugars and starches present in biomass feedstocks into biofuels such as ethanol and butanol. It is commonly used in the production of bioethanol from sugarcane, corn, and cellulosic biomass.

- Physicochemical Conversion:

- Hydrothermal Processing: Biomass can be converted into biofuels and chemicals through hydrothermal processing, which involves heating biomass in the presence of water at high temperatures and pressures. This process can produce bio-oil, biochar, and syngas.

- Torrefaction: Biomass torrefaction involves heating biomass in the absence of oxygen at temperatures between 200°C and 300°C to produce a dry, energy-dense solid fuel called torrefied biomass or bio-coal.

Biomass conversion technologies offer numerous environmental and economic benefits, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions, waste reduction, rural development, and energy security. However, challenges such as feedstock availability, process efficiency, product quality, and economic viability need to be addressed to realize the full potential of biomass conversion for sustainable energy production and resource utilization.

Research and development efforts are focused on advancing biomass conversion technologies, improving process efficiency, developing new feedstock sources, and exploring integrated biorefinery concepts to maximize the value and sustainability of biomass-derived products. Continued innovation and investment in biomass conversion are essential for transitioning towards a more sustainable and renewable energy future.

Biomass Gasification Plant:

A biomass gasification plant is a facility that converts biomass feedstocks into synthesis gas (syngas) through the thermochemical process of gasification. These plants play a crucial role in the utilization of renewable biomass resources for energy production, offering a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels and contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

Key components and processes of a biomass gasification plant include:

- Feedstock Handling and Preparation: Biomass feedstocks such as wood chips, agricultural residues, forestry waste, or energy crops are received, stored, and prepared for gasification. This may involve drying, grinding, and sizing the feedstock to ensure uniformity and optimize gasification performance.

- Gasification Reactor: The heart of the biomass gasification plant is the gasifier, where biomass feedstocks undergo thermochemical reactions in a controlled environment with limited oxygen or steam. Gasifiers can be of various types, including fixed-bed, fluidized-bed, entrained-flow, or downdraft gasifiers, each with its unique characteristics and operating conditions.

- Gasification Process: In the gasification reactor, biomass feedstocks are subjected to high temperatures (typically between 700°C and 1,200°C) and a controlled supply of gasification agent (oxygen, steam, or a combination) to produce syngas. The gasification process involves several chemical reactions, including pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction, leading to the conversion of biomass into syngas.

- Syngas Cleanup: The raw syngas produced from biomass gasification contains impurities such as tar, particulate matter, and contaminants that need to be removed to meet quality specifications for downstream applications. Syngas cleanup systems, including cyclones, scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters, are employed to remove impurities and improve syngas quality.

- Syngas Utilization: The cleaned syngas can be utilized for various energy and chemical applications, including power generation, heat production, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis. Syngas can be burned directly in gas turbines, boilers, or engines to generate electricity or heat. Alternatively, it can be further processed to separate and purify individual gas components for use in chemical processes or as fuel for hydrogen fuel cells.

- Waste Management: Biomass gasification plants may produce by-products such as ash, char, and wastewater during the gasification process. Proper waste management and disposal practices are implemented to handle these by-products safely and minimize environmental impacts.

Biomass gasification plants offer several advantages over conventional combustion-based energy systems, including higher energy efficiency, lower emissions, and greater fuel flexibility. They enable the utilization of a wide range of biomass feedstocks, including agricultural residues, forestry waste, energy crops, and organic waste materials, for clean and sustainable energy production.

Continued research and development efforts are focused on advancing biomass gasification technology, improving process efficiency, enhancing syngas cleanup systems, and exploring integrated biorefinery concepts to maximize the value and sustainability of biomass-derived products. Biomass gasification plants represent a promising pathway towards a more sustainable and renewable energy future, contributing to energy security, environmental protection, and rural development.

Syngas Generator:

A syngas generator, also known as a gas generator or gasifier, is a device or system that produces synthesis gas (syngas) through the gasification of carbonaceous feedstocks such as coal, biomass, or municipal solid waste. Syngas generators play a vital role in converting these feedstocks into a versatile energy carrier that can be utilized for various applications, including power generation, heat production, chemical synthesis, and hydrogen production.

Key components and processes of a syngas generator include:

- Gasification Reactor: The gasification reactor is the core component of the syngas generator, where carbonaceous feedstocks undergo thermochemical reactions in a controlled environment with a limited supply of oxygen, steam, or a combination of both. Gasification reactors can be of different designs, including fixed-bed, fluidized-bed, entrained-flow, or downdraft gasifiers, each offering unique advantages and operating characteristics.

- Feedstock Handling and Preparation: Carbonaceous feedstocks such as coal, biomass, or municipal solid waste are received, stored, and prepared for gasification. Feedstock preparation may involve drying, shredding, grinding, and sizing to optimize gasification performance and ensure uniform fuel distribution in the gasifier.

- Gasification Process: In the gasification reactor, carbonaceous feedstocks are subjected to high temperatures (typically between 700°C and 1,200°C) and a controlled supply of gasification agent (oxygen, steam, or air) to produce syngas. The gasification process involves several thermochemical reactions, including pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction, leading to the conversion of carbonaceous feedstocks into syngas.

- Syngas Cleanup: The raw syngas produced from the gasification process contains impurities such as tar, particulate matter, sulfur compounds, and contaminants that need to be removed to meet quality specifications for downstream applications. Syngas cleanup systems, including cyclones, scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters, are employed to remove impurities and improve syngas quality.

- Syngas Utilization: The cleaned syngas can be utilized for various energy and chemical applications, including power generation, heat production, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis. Syngas can be burned directly in gas turbines, boilers, or engines to generate electricity or heat. Alternatively, it can be further processed to separate and purify individual gas components for use in chemical processes or as fuel for hydrogen fuel cells.

Syngas generators offer several advantages over conventional combustion-based energy systems, including higher energy efficiency, lower emissions, and greater fuel flexibility. They enable the utilization of a wide range of carbonaceous feedstocks, including coal, biomass, agricultural residues, and municipal solid waste, for clean and sustainable energy production.

Continued research and development efforts are focused on advancing syngas generator technology, improving process efficiency, enhancing syngas cleanup systems, and exploring novel applications for syngas in the transition towards a low-carbon economy. Syngas generators represent a promising pathway towards a more sustainable and renewable energy future, contributing to energy security, environmental protection, and economic development.

Gasification Process:

The gasification process is a thermochemical conversion method that transforms carbonaceous feedstocks, such as coal, biomass, or municipal solid waste, into a gaseous mixture known as synthesis gas (syngas). This process occurs in a gasifier, where feedstocks are subjected to high temperatures and a controlled supply of oxygen, steam, or a combination of both, in a low-oxygen environment. The gasification process involves several key steps and reactions:

- Pyrolysis: The initial stage of the gasification process involves heating the carbonaceous feedstock in the absence of oxygen to temperatures typically ranging from 500°C to 800°C. This thermochemical decomposition, known as pyrolysis, breaks down complex organic molecules in the feedstock into smaller hydrocarbons, volatile gases, and char.

- Oxidation: Once the feedstock is heated and partially decomposed, a controlled supply of oxygen, steam, or air is introduced into the gasifier to initiate the oxidation reactions. These reactions involve the combustion of carbonaceous material with oxygen or the reaction of carbon with steam to produce carbon monoxide and hydrogen. The overall reactions can be represented as follows:

- C + O2 → CO2

- C + H2O → CO + H2

- Reduction: As the carbonaceous material reacts with oxygen or steam, the temperature in the gasifier increases, and the resulting carbon dioxide and water vapor interact with the remaining carbon to produce additional syngas components through reduction reactions:

- CO2 + C → 2CO

- H2O + C → CO + H2

- Tar and Char Formation: During the gasification process, some of the carbonaceous material may undergo incomplete conversion, leading to the formation of tar and char residues. Tar consists of complex hydrocarbons that can condense on surfaces and equipment, while char is the solid residue remaining after pyrolysis and gasification reactions.

- Syngas Composition: The composition of the syngas produced from gasification depends on factors such as the feedstock type, gasification conditions, and gasifier design. Typical syngas composition includes hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and trace amounts of other gases such as nitrogen (N2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and ammonia (NH3).

The syngas produced from the gasification process is a versatile energy carrier that can be utilized for various applications, including power generation, heat production, chemical synthesis, and hydrogen production. Syngas can be burned directly in gas turbines, boilers, or engines to generate electricity or heat, or further processed to separate and purify individual gas components for use in chemical processes or as fuel for hydrogen fuel cells.

Gasification offers several advantages over conventional combustion-based energy systems, including higher energy efficiency, lower emissions, and greater fuel flexibility. It enables the utilization of a wide range of carbonaceous feedstocks for clean and sustainable energy production, contributing to energy security, environmental protection, and economic development. Continued research and development efforts are focused on advancing gasification technology, improving process efficiency, and exploring novel applications for syngas in the transition towards a low-carbon economy.

Gasification Plant Design and Operation:

Gasification plants are complex facilities designed to efficiently convert various carbonaceous feedstocks into valuable synthesis gas (syngas) through the process of gasification. The design and operation of gasification plants involve numerous considerations to ensure optimal performance, reliability, and safety. Here are some key aspects of gasification plant design and operation:

- Feedstock Selection and Preparation: Gasification plants can utilize a wide range of feedstocks, including coal, biomass, municipal solid waste, and industrial residues. The selection of feedstock depends on factors such as availability, cost, energy content, and environmental impact. Feedstock preparation involves handling, sizing, drying, and sometimes pre-treatment to optimize gasification efficiency and feedstock utilization.

- Gasification Reactor Design: Gasification reactors are the core components of gasification plants, where feedstocks undergo thermochemical reactions to produce syngas. Reactor design considerations include reactor type (e.g., fixed-bed, fluidized-bed, entrained-flow), operating temperature and pressure, residence time, gasification agent (oxygen, air, steam), and feedstock feeding mechanism. The choice of reactor design depends on factors such as feedstock characteristics, gasification process requirements, and desired syngas composition.

- Gasification Process Control: Gasification plants require robust process control systems to monitor and regulate various parameters such as temperature, pressure, gas flow rates, feedstock feeding rates, and gas composition. Advanced control strategies, including feedback and feedforward control loops, are employed to maintain stable and efficient operation, optimize performance, and ensure safety.

- Syngas Cleanup and Conditioning: The raw syngas produced from the gasification process contains impurities such as tar, particulate matter, sulfur compounds, and contaminants that need to be removed to meet quality specifications for downstream applications. Syngas cleanup systems, including cyclones, scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters, are employed to remove impurities and improve syngas quality. Syngas conditioning processes such as cooling, drying, and compression may also be required to prepare syngas for further processing and utilization.

- Syngas Utilization and Integration: The cleaned syngas can be utilized for various energy and chemical applications, including power generation, heat production, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis. Gasification plants may be integrated with other processes such as combined heat and power (CHP) systems, gas-to-liquid (GTL) processes, or integrated biorefineries to maximize resource utilization, energy efficiency, and product value.

- Safety and Environmental Considerations: Gasification plant design and operation must comply with strict safety regulations and environmental standards to minimize risks to personnel, communities, and ecosystems. Measures such as process safety management, risk assessment, emissions monitoring, and waste management are implemented to ensure safe and environmentally responsible operation.

Overall, the successful design and operation of gasification plants require interdisciplinary expertise in engineering, chemistry, process control, and environmental science. Continued research and development efforts are focused on advancing gasification technology, improving process efficiency, and reducing environmental impacts to realize the full potential of gasification for sustainable energy production and resource utilization.

Gasification Plant Economics and Feasibility Analysis:

Gasification plants represent significant investments in capital, operation, and maintenance costs. Conducting thorough economic and feasibility analyses is crucial to evaluate the financial viability of such projects and make informed investment decisions. Here’s an overview of the key aspects involved in assessing the economics and feasibility of gasification plants:

- Cost Estimation: The first step in economic analysis is estimating the capital costs associated with designing, constructing, and commissioning the gasification plant. This includes costs for equipment, materials, labor, engineering services, permitting, and land acquisition. Operational costs, including feedstock procurement, labor, maintenance, utilities, and waste disposal, are also estimated.

- Revenue Generation: Gasification plants generate revenue through the sale of syngas and other by-products such as heat, electricity, chemicals, or biofuels. Revenue streams depend on market prices for syngas and by-products, as well as demand dynamics, regulatory incentives, and competition. Long-term contracts, off-take agreements, or feedstock supply agreements may secure revenue streams and mitigate market risks.

- Financial Modeling: Financial modeling involves projecting cash flows, revenues, expenses, and returns over the project’s lifecycle. Discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), payback period, and profitability indices are commonly used metrics to assess project economics and compare investment alternatives. Sensitivity analysis helps evaluate the impact of uncertain variables such as feedstock prices, energy prices, and regulatory changes on project returns.

- Risk Assessment: Gasification projects entail various risks that may affect their economic viability, including technical risks (e.g., technology performance, reliability, scalability), market risks (e.g., commodity prices, demand uncertainty), financial risks (e.g., capital cost overruns, financing costs), regulatory risks (e.g., environmental compliance, policy changes), and operational risks (e.g., feedstock availability, equipment downtime). Risk assessment and mitigation strategies, such as insurance, hedging, contingency planning, and diversification, are essential to manage project risks and enhance financial resilience.

- Market Analysis: Market analysis involves assessing the demand for syngas and by-products, identifying potential customers and end-users, understanding market dynamics, and evaluating competitive landscape and pricing trends. Market studies help validate revenue projections, identify market opportunities, and formulate marketing and sales strategies to maximize project profitability.

- Regulatory Compliance: Gasification projects must comply with local, state, and federal regulations governing environmental, health, safety, and land use aspects. Permitting requirements, emissions standards, waste disposal regulations, and financial incentives such as tax credits or subsidies may impact project economics and feasibility. Engaging with regulatory authorities, conducting environmental impact assessments, and obtaining necessary permits are essential steps in project development.

- Social and Environmental Impact Assessment: Gasification projects may have social and environmental impacts on local communities, ecosystems, and stakeholders. Conducting social and environmental impact assessments (SEIA) helps identify potential risks, assess mitigation measures, and incorporate sustainability considerations into project planning and decision-making. Stakeholder engagement, community consultation, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives are integral to building trust, managing reputational risks, and ensuring sustainable development outcomes.

Overall, conducting comprehensive economic and feasibility analyses is essential to evaluate the financial, technical, market, regulatory, and social aspects of gasification projects and make informed investment decisions. Collaboration with multidisciplinary teams, stakeholders, financial institutions, and industry partners can help address challenges, mitigate risks, and optimize project outcomes for successful project development and implementation.

Gasification Plant Environmental Impact:

Gasification plants offer numerous benefits in terms of energy production, resource utilization, and waste management. However, they also have environmental impacts that need to be carefully assessed, managed, and mitigated to ensure sustainable development and minimize adverse effects on ecosystems, air quality, and human health. Here are some key environmental considerations associated with gasification plants:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Gasification of carbonaceous feedstocks produces carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, although typically at lower levels compared to conventional combustion processes. However, gasification can also produce methane (CH4) emissions, particularly if not properly managed. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a higher global warming potential than CO2, so controlling methane emissions is essential to minimize the plant’s overall greenhouse gas footprint.

- Particulate Matter and Air Quality: Gasification processes can generate particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and other air pollutants, depending on the feedstock composition and gasification conditions. These pollutants can contribute to local air quality degradation, respiratory illnesses, and environmental damage. Implementing effective emissions control technologies such as electrostatic precipitators, scrubbers, and catalytic converters is essential to reduce emissions and protect air quality.

- Ash Disposal and Waste Management: Gasification produces ash and other solid residues as by-products, which require proper handling, storage, and disposal to prevent environmental contamination. Ash disposal methods include landfilling, recycling for beneficial use in construction materials or agriculture, and thermal treatment to reduce volume and toxicity. Effective waste management practices minimize the risk of soil and water contamination, groundwater pollution, and ecosystem degradation.

- Water Usage and Pollution: Gasification plants require water for cooling, steam generation, syngas cleaning, and other process-related activities. Water consumption and wastewater discharge can affect local water resources, aquatic ecosystems, and downstream water quality. Implementing water conservation measures, recycling and reusing process water, and treating wastewater to meet regulatory standards help minimize water usage and pollution impacts.

- Land Use and Habitat Impact: Gasification plants require land for site development, construction, and operation, which may result in habitat loss, ecosystem fragmentation, and biodiversity impacts. Land use planning, environmental impact assessments, and habitat restoration measures are essential to minimize land use conflicts, protect sensitive habitats, and preserve biodiversity. Incorporating green infrastructure, landscaping, and vegetation buffers can enhance site aesthetics and ecological value.

- Noise and Visual Impact: Gasification plants can generate noise and visual disturbances during construction and operation, which may affect nearby communities and wildlife habitats. Implementing noise abatement measures such as sound barriers, acoustic enclosures, and operational controls help reduce noise levels and mitigate community annoyance. Visual screening, landscaping, and aesthetic design considerations can minimize visual impacts and integrate the plant into the surrounding landscape.

- Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: Despite their environmental impacts, gasification plants can contribute to climate change mitigation by displacing fossil fuel-based energy sources, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and supporting the transition to a low-carbon economy. Implementing carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies can further enhance the plant’s climate change mitigation potential by capturing and sequestering CO2 emissions underground.

Overall, assessing and managing the environmental impacts of gasification plants require comprehensive environmental monitoring, regulatory compliance, stakeholder engagement, and continuous improvement initiatives. Integrating environmental considerations into project planning, design, and operation helps minimize adverse impacts, enhance environmental performance, and promote sustainable development of gasification projects.

Gasification Plant Safety and Risk Management:

Gasification plants are complex industrial facilities that involve high temperatures, pressures, and potentially hazardous materials. Ensuring safety and managing risks is paramount to protect personnel, communities, and the environment. Here are key aspects of gasification plant safety and risk management:

- Process Safety Management (PSM): Gasification plants implement rigorous process safety management systems to identify, evaluate, and control hazards associated with gasification processes. This includes conducting process hazard analyses (PHA), risk assessments, and safety reviews to identify potential hazards, assess their likelihood and consequences, and implement risk mitigation measures.

- Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS): Gasification plants utilize safety instrumented systems to automatically detect and respond to abnormal conditions or process upsets to prevent accidents and protect personnel and equipment. Safety systems such as emergency shutdown systems (ESD), fire and gas detection systems, and pressure relief devices are designed to activate and mitigate hazards before they escalate.

- Emergency Response Planning: Gasification plants develop comprehensive emergency response plans (ERP) to address potential accidents, spills, fires, or other emergencies. ERP includes procedures for personnel evacuation, emergency communication, first aid, firefighting, spill containment, and coordination with local emergency services. Regular emergency drills and training exercises ensure preparedness and response effectiveness.

- Occupational Health and Safety (OHS): Gasification plants prioritize occupational health and safety to protect workers from workplace hazards and ensure a safe working environment. This includes implementing safety training programs, providing personal protective equipment (PPE), conducting job hazard analyses (JHA), and promoting a culture of safety awareness and accountability among employees.

- Hazardous Materials Management: Gasification plants handle and process potentially hazardous materials such as flammable gases, toxic chemicals, and combustible dusts. Proper handling, storage, labeling, and disposal of hazardous materials are essential to prevent accidents, spills, leaks, and environmental contamination. Material safety data sheets (MSDS), chemical inventories, and spill response procedures help manage hazardous materials safely.

- Fire Protection and Prevention: Gasification plants implement fire protection and prevention measures to minimize the risk of fires and explosions. This includes installing fire detection and suppression systems, maintaining fire hydrants and extinguishers, conducting fire risk assessments, and implementing hot work permits and fire safety protocols.

- Security and Access Control: Gasification plants implement security measures to protect critical infrastructure, equipment, and personnel from unauthorized access, sabotage, terrorism, or vandalism. Security measures may include perimeter fencing, access controls, surveillance cameras, security patrols, and cybersecurity protocols to safeguard plant operations and data systems.

- Environmental Risk Management: Gasification plants assess and manage environmental risks associated with air emissions, water usage, waste disposal, and ecosystem impacts. This includes monitoring and controlling emissions, implementing spill prevention and response measures, managing waste streams, and conducting environmental impact assessments (EIA) to minimize environmental liabilities and comply with regulatory requirements.

By implementing robust safety management systems, risk assessment methodologies, and emergency response procedures, gasification plants can effectively mitigate hazards, protect personnel and assets, and ensure safe and sustainable operation throughout the plant lifecycle. Continuous monitoring, evaluation, and improvement of safety performance are essential to maintain a high level of safety culture and resilience in the face of evolving risks and challenges.

Gasification Plant Commissioning and Operations:

Gasification plant commissioning and operations involve a series of critical steps and ongoing activities to ensure the efficient and reliable production of syngas while maintaining safety, environmental compliance, and economic performance. Here’s an overview of key aspects of gasification plant commissioning and operations:

- Commissioning Planning: Prior to startup, a comprehensive commissioning plan is developed to systematically test and verify the performance of all plant systems and equipment. This includes pre-commissioning activities such as equipment inspections, system flushing, and mechanical integrity testing, followed by functional testing, performance testing, and final acceptance testing.

- Startup Procedures: Gasification plant startup involves gradually bringing the plant online, starting with non-critical systems and gradually ramping up to full operation. Startup procedures include equipment warm-up, system pressurization, fuel feeding, ignition, and synchronization of auxiliary systems such as air and steam supply. Startup is conducted in accordance with established procedures and under close supervision to ensure safe and controlled operation.

- Process Optimization: Once the plant is operational, ongoing process optimization efforts are undertaken to maximize efficiency, productivity, and product quality while minimizing energy consumption, emissions, and operating costs. This may involve adjusting operating parameters such as temperature, pressure, feedstock composition, and gasification agent flow rates to optimize syngas yield and composition.

- Maintenance and Reliability: Gasification plant maintenance programs are implemented to ensure the reliability and availability of critical equipment and systems. This includes preventive maintenance activities such as equipment inspections, lubrication, cleaning, and replacement of worn components, as well as predictive maintenance techniques such as condition monitoring, vibration analysis, and thermography to identify and address potential issues before they lead to downtime or failure.

- Safety Management: Safety remains a top priority during plant operations, with stringent safety protocols, procedures, and training programs in place to protect personnel, equipment, and the environment. Safety audits, inspections, and incident investigations are conducted regularly to identify hazards, assess risks, and implement corrective actions to prevent accidents and ensure compliance with regulatory requirements.

- Environmental Compliance: Gasification plant operations are subject to environmental regulations governing air emissions, water discharge, waste management, and other environmental aspects. Continuous emissions monitoring, effluent testing, and environmental reporting are conducted to ensure compliance with permit limits and regulatory standards. Pollution control technologies such as scrubbers, filters, and catalytic converters are employed to minimize emissions and mitigate environmental impacts.

- Quality Control: Syngas quality is monitored and controlled to meet specified product specifications and end-user requirements. Analytical instrumentation and process control systems are utilized to measure key parameters such as gas composition, heating value, sulfur content, and particulate emissions. Quality assurance measures are implemented to ensure consistent product quality and performance.

- Training and Skills Development: Gasification plant personnel receive comprehensive training and skills development to operate and maintain the plant safely and efficiently. Training programs cover plant operations, safety procedures, emergency response protocols, environmental compliance, and equipment maintenance. Ongoing skills development initiatives ensure that operators and maintenance personnel remain proficient in their roles and capable of adapting to evolving technologies and operational challenges.

By implementing effective commissioning, startup, and operational practices, gasification plants can achieve reliable, safe, and environmentally responsible production of syngas for various energy and chemical applications. Continuous monitoring, optimization, and improvement efforts are essential to maximize plant performance, minimize risks, and ensure long-term viability and competitiveness in the evolving energy landscape.

Biomass to Energy

Biomass Feedstock:

Biomass feedstock refers to the organic materials used as raw inputs for biomass-to-energy processes. These materials are derived from various renewable sources such as agricultural residues, forestry residues, energy crops, animal waste, municipal solid waste, and organic industrial waste. Biomass feedstock can be classified into different categories based on their origin, composition, and physical properties.

Agricultural residues, including crop residues (such as straw, husks, and stalks) and processing residues (such as bagasse and pomace), are abundant sources of biomass feedstock. Forestry residues, such as logging residues, sawdust, and wood chips, are generated during forest harvesting and processing activities. Energy crops, such as switchgrass, miscanthus, and willow, are cultivated specifically for biomass production and can be harvested annually or on a rotational basis.

Animal waste, including manure from livestock operations and poultry farms, contains organic matter that can be converted into biogas through anaerobic digestion processes. Municipal solid waste (MSW) and organic industrial waste, such as food processing residues and paper mill sludge, represent urban biomass resources that can be diverted from landfills and incinerators for energy recovery.

The selection of biomass feedstock depends on various factors, including availability, cost, energy content, moisture content, ash content, and sustainability considerations. Feedstock preprocessing may be required to remove impurities, reduce particle size, and enhance energy density for efficient handling, storage, and conversion. Biomass feedstock sustainability involves assessing its environmental, social, and economic impacts throughout its lifecycle, including land use, water use, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity, and socioeconomic benefits.

Overall, biomass feedstock plays a critical role in biomass-to-energy processes, providing renewable and sustainable sources of fuel and energy for power generation, heat production, biofuels production, and other applications. Effective management of biomass feedstock resources is essential to ensure efficient, reliable, and environmentally responsible utilization of biomass for energy purposes.

Anaerobic Digestion:

Anaerobic digestion is a biological process that converts organic materials into biogas and organic residues in the absence of oxygen. It is a natural process that occurs in anaerobic environments, such as landfills, wetlands, and the digestive systems of animals. In controlled environments, anaerobic digestion is widely used to treat organic waste and produce renewable energy in the form of biogas.

The anaerobic digestion process involves a series of biochemical reactions carried out by a diverse community of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, and fungi. These microorganisms break down complex organic compounds present in the feedstock into simpler molecules, such as volatile fatty acids, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide. Methanogenic archaea then metabolize these intermediate products to produce methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) through a process known as methanogenesis.

Anaerobic digestion can be divided into four main stages: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis. During hydrolysis, complex organic molecules are broken down into soluble compounds by hydrolytic enzymes. In the acidogenesis stage, acid-forming bacteria further break down these compounds into volatile fatty acids, alcohols, and other organic acids. Acetogenic bacteria then convert these compounds into acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide during acetogenesis. Finally, methanogenic archaea convert acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide into methane and carbon dioxide during methanogenesis.

Biogas produced through anaerobic digestion typically consists of 50-70% methane (CH4) and 30-50% carbon dioxide (CO2), along with trace amounts of other gases such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and ammonia (NH3). Biogas can be used as a renewable fuel for electricity generation, heat production, vehicle fuel, or upgraded to biomethane for injection into natural gas pipelines or use as a transportation fuel.