Working Fluid for ORC Turbines: Organic Rankine Cycle is a thermodynamic cycle that is similar to the traditional Rankine cycle (used in steam turbines), but it uses an organic fluid (such as refrigerants or other hydrocarbons) instead of water or steam. This allows ORC systems to generate power from low-grade heat sources (like geothermal, industrial waste heat, or solar thermal).

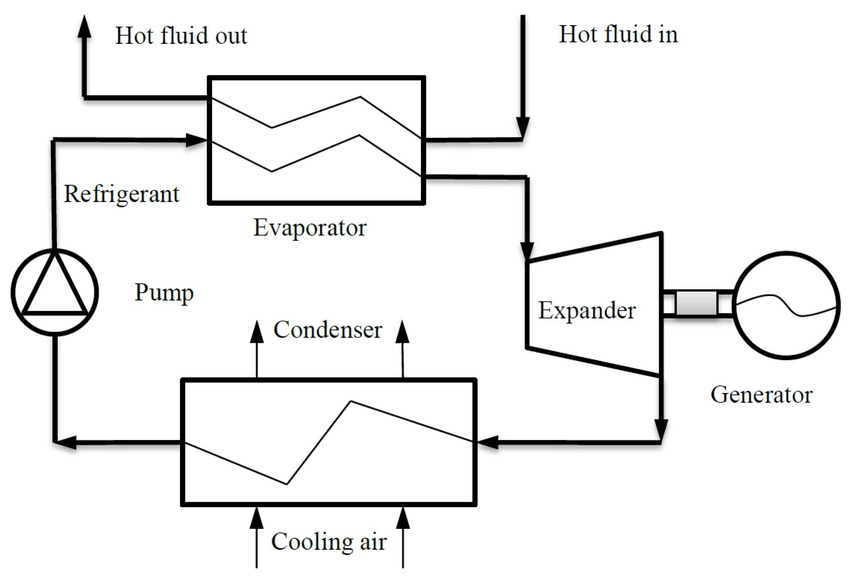

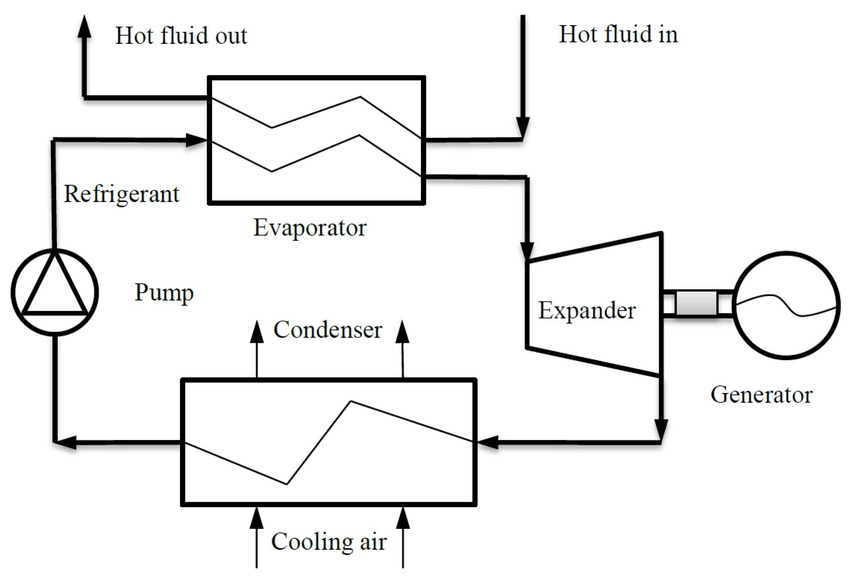

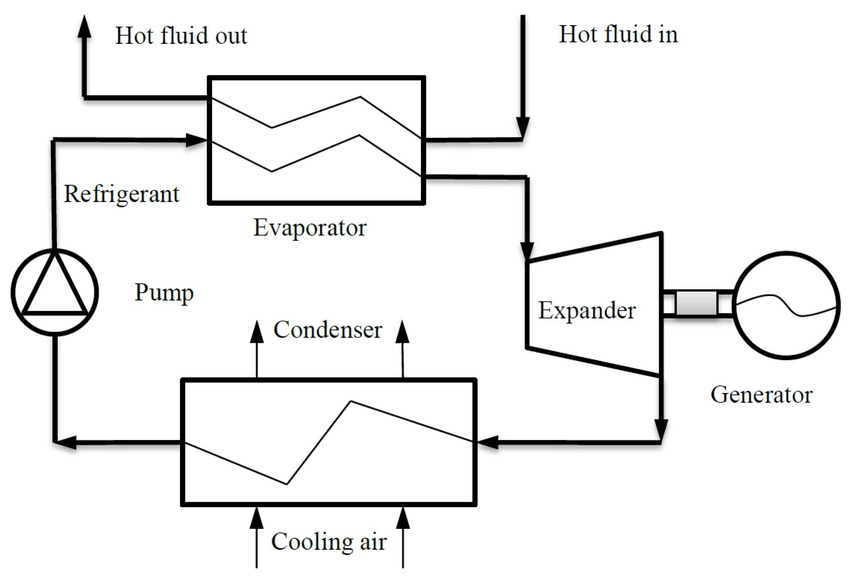

Here’s how it works in a nutshell:

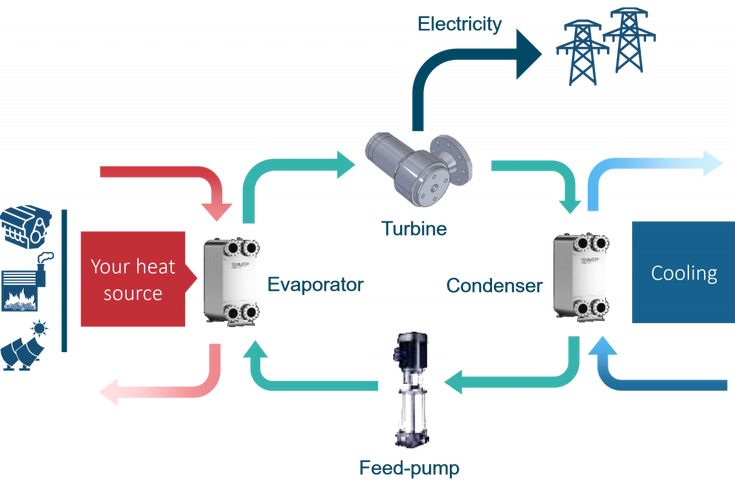

- Heat Source: The system uses a heat source, typically low-temperature heat (e.g., 80°C to 300°C), to evaporate the organic fluid.

- Evaporator: The organic fluid is pumped through a heat exchanger where it absorbs heat from the heat source. As it absorbs heat, the fluid evaporates, turning into a vapor.

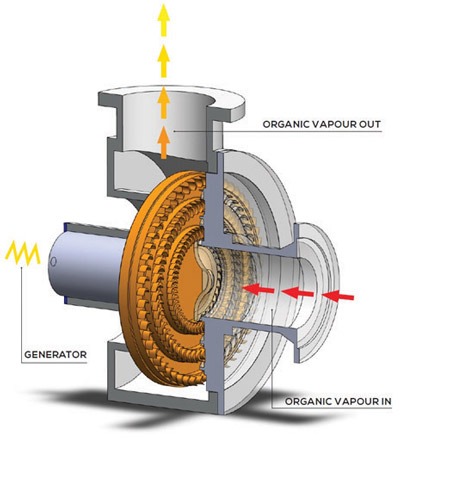

- Turbine: The vaporized organic fluid is then directed to a turbine. The vapor expands through the turbine, causing it to spin. This mechanical energy is converted into electrical energy by a generator.

- Condenser: After passing through the turbine, the vapor is then cooled in a condenser, where it releases heat and condenses back into a liquid form.

- Pump: The condensed liquid is then pumped back into the evaporator to repeat the cycle.

The main advantage of an ORC system is its ability to use lower temperature heat sources, making it useful for applications like recovering waste heat from industrial processes, geothermal energy, or even solar thermal energy.

The Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) operates by using a low-temperature heat source to heat an organic fluid, typically a refrigerant or hydrocarbon. This fluid is pumped through a heat exchanger, where it absorbs heat and vaporizes. The vapor is then directed to a turbine, where it expands and drives a generator to produce electricity. After passing through the turbine, the vapor is cooled in a condenser, where it releases its heat and turns back into a liquid. This liquid is pumped back to the heat exchanger, and the cycle repeats. ORC systems are particularly useful for harnessing waste heat or low-temperature heat sources, making them ideal for applications like geothermal energy, industrial waste heat recovery, or solar thermal energy. Their ability to operate at lower temperatures than traditional steam-based Rankine cycles makes them more versatile for specific applications.

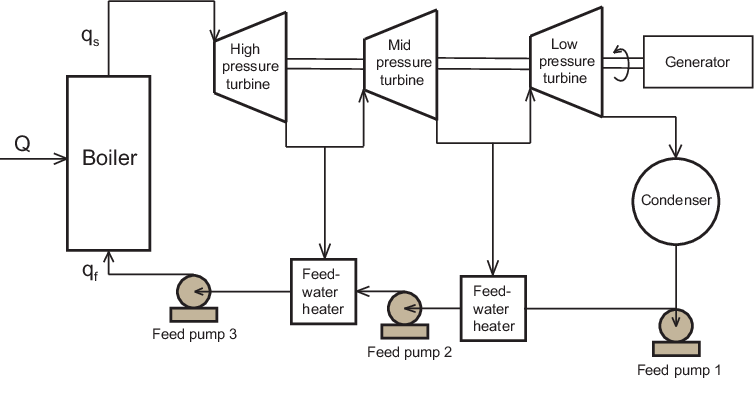

The Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) is a thermodynamic process that is similar to the conventional Rankine cycle used in steam turbine systems but employs an organic fluid instead of water or steam. This fundamental difference in the working fluid allows ORC systems to effectively utilize lower temperature heat sources to generate power, offering an advantage over traditional Rankine cycles, which typically require high-temperature steam.

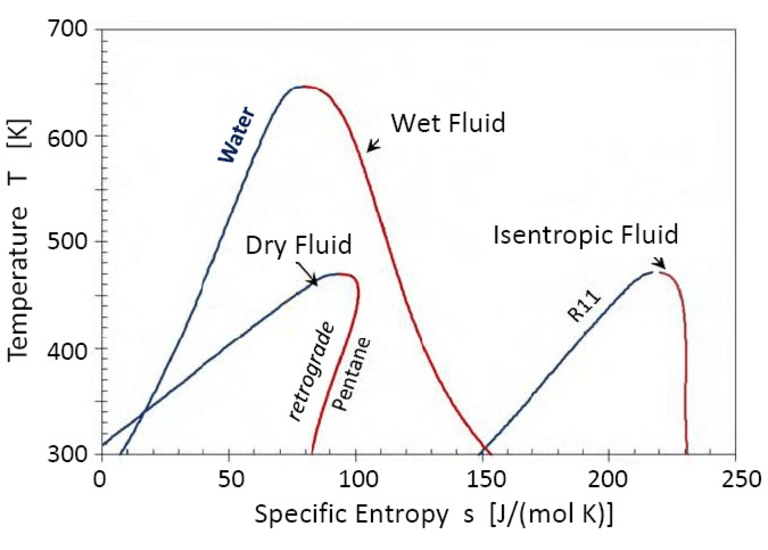

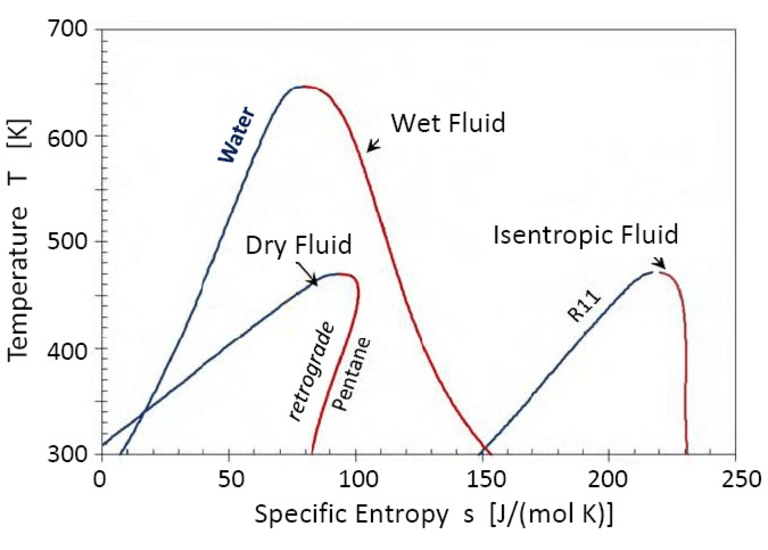

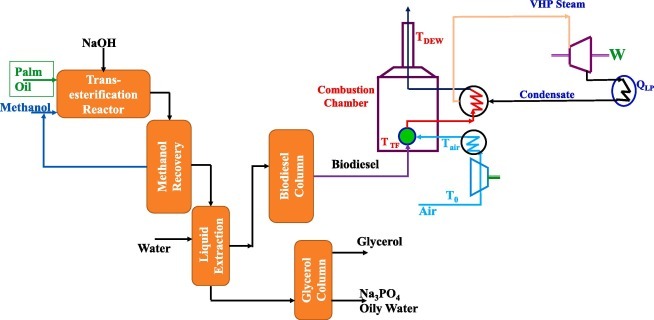

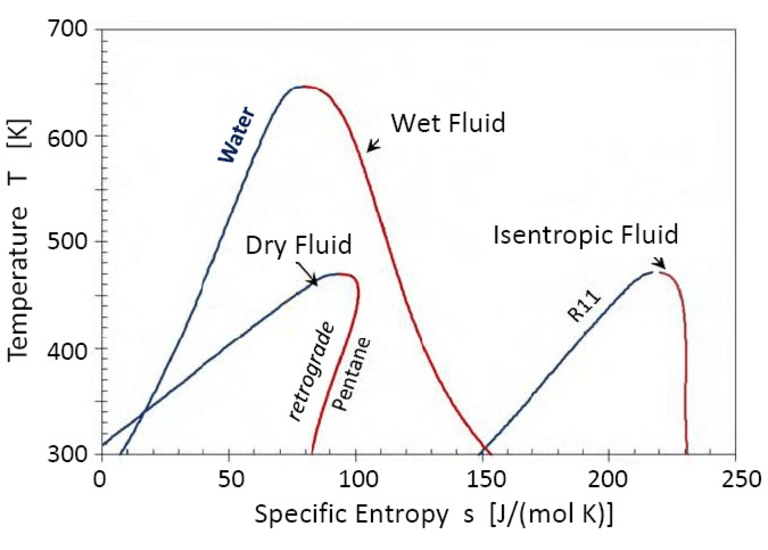

The cycle begins with a heat source, which could be anything from industrial waste heat, geothermal energy, biomass, solar thermal energy, or even heat recovered from other industrial processes. This heat is transferred to the organic fluid in the evaporator, causing it to vaporize. The organic fluid is carefully selected based on its boiling point and thermodynamic properties, which enable it to evaporate at lower temperatures than water. Some commonly used fluids in ORC systems include refrigerants like R245fa, hydrocarbons like n-pentane, or other synthetic organic fluids that have desirable characteristics such as low environmental impact, high efficiency at lower temperatures, and non-corrosiveness.

Once the organic fluid has been vaporized, it moves into a turbine, where the pressurized vapor expands and loses its pressure, causing it to spin the turbine blades. This mechanical energy from the turbine is converted into electrical energy through a connected generator. The efficiency of the turbine and the choice of organic fluid are important factors in the overall performance of the system. As the vapor passes through the turbine, it undergoes a thermodynamic expansion process, similar to steam in a traditional Rankine cycle, but because the ORC uses an organic fluid, it can operate effectively at lower temperatures and pressures.

After passing through the turbine, the now-expanded vapor enters a condenser, where it is cooled by a secondary medium such as air or water. As the vapor loses heat to the cooling medium, it condenses back into a liquid state. This liquid is then sent through a pump that raises its pressure, and the cycle repeats.

The ability to use lower temperature heat is one of the key benefits of the ORC. While conventional steam-based Rankine cycles require heat sources that can generate temperatures of around 400°C or more, ORC systems can generate power from heat sources in the range of 80°C to 300°C. This opens up many opportunities for utilizing low-grade heat sources, which are otherwise not feasible for traditional steam turbines.

The ORC is increasingly used in a wide range of applications due to its ability to convert low-temperature thermal energy into electricity efficiently. One of the most significant uses is in geothermal power generation. Geothermal energy, which is often at relatively low temperatures compared to other energy sources, is a perfect candidate for ORC systems, making it possible to harness geothermal heat even in regions with less intense geothermal activity. Similarly, in industrial settings, ORC systems can be used to recover waste heat from processes like cement manufacturing, steel production, or chemical plants, where large amounts of heat are generated as byproducts.

Another promising application of the ORC is in solar thermal power plants, particularly those that use concentrated solar power (CSP) systems. CSP systems focus sunlight onto a heat exchanger to generate high temperatures, and when paired with ORC technology, they can convert this heat into electricity efficiently. The low operating temperature range of ORC systems is well suited to the temperature levels produced in many CSP systems.

In addition to waste heat recovery and renewable energy applications, ORC systems can also be used in waste-to-energy plants, district heating, and even in mobile applications like waste heat recovery for trucks or marine vessels. The versatility of ORC technology is due to its ability to efficiently capture and convert heat at lower temperatures, which can help improve overall energy efficiency and reduce emissions by utilizing heat that would otherwise go unused.

Another noteworthy feature of ORC systems is their relatively simple operation and smaller environmental footprint compared to traditional steam-based Rankine cycle systems. Since the operating pressures and temperatures are lower, ORC systems are often more compact and less expensive to maintain. Additionally, many of the fluids used in ORC cycles have lower environmental impacts than water-steam systems, and advancements in fluid selection continue to improve the sustainability and efficiency of ORC-based systems.

The ORC technology also has the advantage of scalability. Whether for small-scale decentralized energy generation or larger, more industrial applications, ORC systems can be designed to meet a wide variety of energy demands. This scalability, combined with the ability to utilize diverse heat sources, makes the Organic Rankine Cycle an attractive solution for both developed and developing regions seeking efficient, clean energy options.

In summary, the Organic Rankine Cycle is a promising technology that allows for the efficient conversion of low-grade thermal energy into electrical power. Its ability to operate at lower temperatures, its use of environmentally friendly organic fluids, and its versatility in a wide range of applications make it a key player in the shift toward more sustainable and efficient energy systems. Whether used in geothermal plants, industrial waste heat recovery, or solar thermal power generation, ORC systems provide an important tool for optimizing energy usage and minimizing environmental impact.

Building on the previous overview, the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) continues to evolve as a key technology in the renewable energy sector and energy efficiency initiatives across various industries. Its potential is particularly valuable in addressing both energy demands and environmental concerns, making it an attractive alternative for many applications.

Advancements in Organic Fluids and System Design

One of the major areas of development within ORC technology is the improvement of the organic fluids used in the cycle. These fluids are critical because they determine the efficiency, environmental impact, and operational capabilities of the system. While earlier systems relied on a limited range of fluids, more recent research has focused on developing new fluids that are not only more efficient but also environmentally friendly. The goal is to select fluids that have low global warming potential (GWP), low toxicity, and are non-flammable, making them safer for use in a wide range of environments.

For example, fluids such as R245fa and n-pentane are commonly used due to their good thermodynamic properties, such as low boiling points and high thermal stability, which allow the ORC to operate effectively at lower temperatures. However, research continues into finding even more sustainable fluids, such as natural refrigerants like CO2 and ammonia or hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), which have a smaller environmental footprint. This ongoing innovation in fluid chemistry is helping to further improve the efficiency of ORC systems while minimizing their ecological impact.

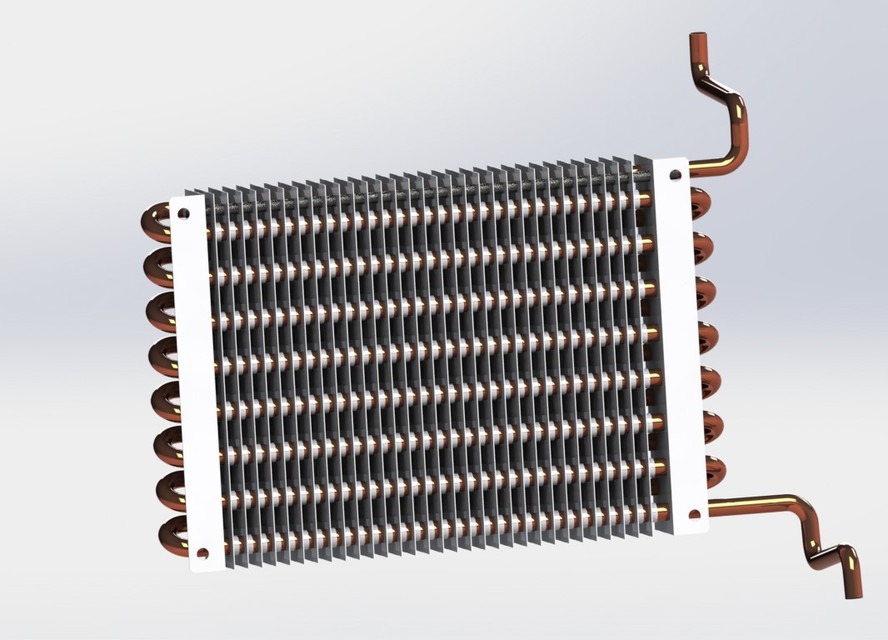

Furthermore, improvements in system design have also made ORC systems more efficient. For instance, the integration of advanced heat exchangers, more efficient turbines, and improved control systems has increased the performance and operational reliability of ORC systems. For example, the use of regenerative heat exchangers, where the working fluid is pre-heated before entering the evaporator, can significantly reduce the amount of energy required to vaporize the fluid, thus improving overall cycle efficiency.

Integration with Other Renewable Energy Sources

ORC technology is particularly well-suited for integration with other renewable energy sources. As mentioned earlier, geothermal energy is one of the most common sources paired with ORC systems, but it can also be combined with solar, biomass, and even waste heat from industrial processes. This integration allows for the creation of hybrid energy systems that can operate more continuously, even during times when one source may not be generating as much power.

For example, in solar thermal power plants, ORC systems can be integrated with concentrated solar power (CSP) technologies. CSP uses mirrors or lenses to focus sunlight onto a small area, generating high temperatures that can be used to produce steam or heat a working fluid. When ORC systems are used alongside CSP, the low boiling point of the organic fluids used in the ORC can capture the heat from CSP more efficiently, even when temperatures aren’t as high as those required for traditional steam cycles. This combination allows CSP plants to operate more efficiently and increase the overall energy output.

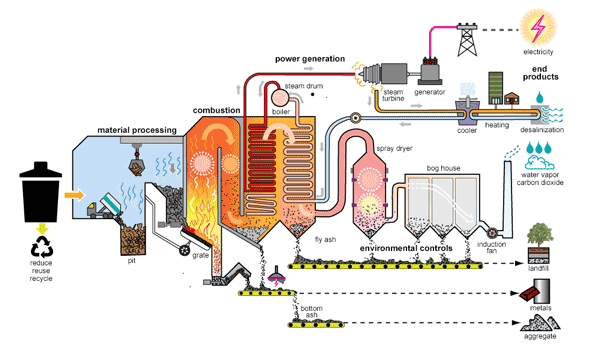

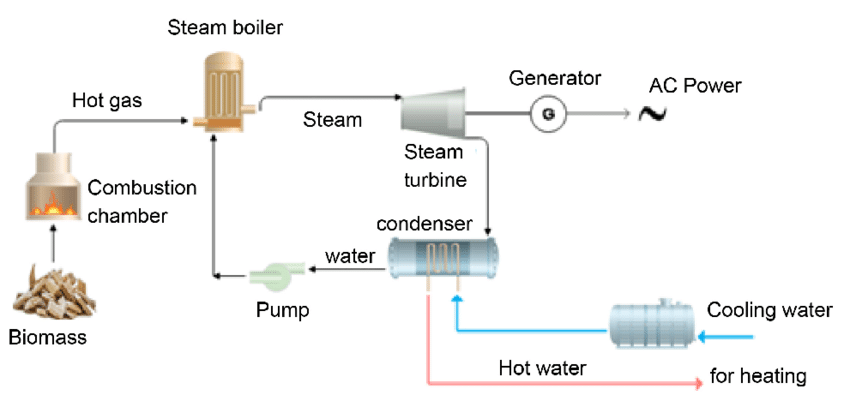

Similarly, the integration of ORC technology with biomass energy generation allows for greater flexibility and reliability. Biomass boilers generate heat by burning organic materials like wood chips or agricultural waste, and an ORC system can help convert this heat into electricity efficiently. Using an ORC system in biomass plants is advantageous because it can convert lower temperature heat into power, something that traditional steam-based turbines cannot do as efficiently.

Another example is industrial waste heat recovery. Many industries produce vast amounts of heat during manufacturing processes, and this heat is often lost to the environment. By using ORC technology to recover this waste heat and convert it into electricity, companies can significantly improve their overall energy efficiency, reduce operational costs, and lower emissions. ORC systems can be used to recover heat from a wide range of industrial processes, such as cement production, steel manufacturing, chemical plants, and even oil refineries.

Economic Benefits and Challenges

Economically, ORC systems offer both opportunities and challenges. One of the biggest advantages is the ability to utilize low-grade waste heat, which is often considered wasted energy. By recovering this waste heat, ORC systems can add value to industrial processes, reduce the energy costs of operations, and generate revenue through the sale of electricity or by providing energy to nearby facilities or grids. In areas where electricity prices are high or where there are incentives for renewable energy generation, the economic benefits of ORC systems become even more apparent.

However, there are also challenges. While ORC systems are becoming more efficient and cost-effective, their upfront costs can still be high compared to other energy systems. This includes the cost of purchasing and installing the ORC units, as well as maintaining the system over time. Additionally, the efficiency of ORC systems can be affected by the temperature and quality of the available heat source, meaning they may not be suitable for all applications, especially those where heat is not consistently available or is too low in temperature.

Moreover, while ORC systems are flexible and can be scaled to different sizes, there can be challenges related to the scalability of some technologies, particularly when adapting ORC systems to smaller or decentralized energy production scenarios. For example, in remote areas or in small-scale applications, the cost of implementing an ORC system can be prohibitive, especially when considering the infrastructure needed to harness and distribute energy.

Future Outlook

Looking ahead, the future of ORC technology appears promising. As more industries, communities, and countries look for ways to reduce their carbon footprint and improve energy efficiency, ORC systems will play a crucial role in meeting these goals. Innovations in fluid technology, turbine design, and system integration will continue to drive improvements in performance, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. In addition, the global push for renewable energy and sustainable practices will increase the demand for systems like ORC, particularly in sectors that produce large amounts of waste heat, such as manufacturing, transportation, and energy production.

With ongoing research and development, it’s likely that ORC technology will become a standard solution for waste heat recovery and renewable energy production. As the systems become more affordable, efficient, and widely adopted, we could see ORC applications expand into new areas, such as small-scale distributed energy generation and mobile energy recovery systems for transportation.

In conclusion, the Organic Rankine Cycle represents an exciting and versatile technology that harnesses low-temperature heat for power generation. By improving energy efficiency and enabling the use of renewable or waste heat sources, ORC systems offer significant potential for reducing global energy consumption and emissions. With continued advancements in fluid selection, system design, and integration with other renewable technologies, ORC is poised to become an essential component of sustainable energy solutions.

ORC Power Plant

An ORC (Organic Rankine Cycle) power plant is a type of power generation facility that uses the Organic Rankine Cycle to convert low-temperature heat into electricity. The ORC power plant is well-suited for applications where traditional steam turbines, based on the Rankine cycle, would not be efficient or feasible due to the low temperature of the available heat source. This can include waste heat recovery, geothermal energy, biomass, or solar thermal energy, among other low-grade thermal sources.

Here’s a breakdown of how an ORC power plant works:

Heat Source and Preprocessing

The first step in an ORC power plant involves sourcing the heat. This could come from a variety of low-temperature thermal sources:

- Geothermal Energy: Geothermal heat is used to heat the working fluid in the ORC system. In a geothermal application, steam or hot water from the Earth’s interior is pumped to the surface, where its heat is transferred to the organic working fluid.

- Industrial Waste Heat: Many industries generate substantial amounts of waste heat during their operations. ORC power plants can harness this waste heat and convert it into electricity, improving overall energy efficiency and reducing emissions.

- Biomass: In biomass power plants, organic material like wood chips, agricultural waste, or other biomass sources are burned to produce heat, which is then used to power the ORC system.

- Solar Thermal Energy: Concentrated solar power (CSP) systems can be paired with ORC plants to generate electricity from solar heat. CSP systems use mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight onto a small area, heating a working fluid to high temperatures. This heat can then be used in the ORC cycle to generate electricity.

The key advantage of an ORC system is its ability to operate at much lower temperatures (around 80°C to 300°C) than conventional steam Rankine cycle systems, which require much higher temperatures. This makes ORC plants ideal for utilizing these low-grade heat sources.

Components of an ORC Power Plant

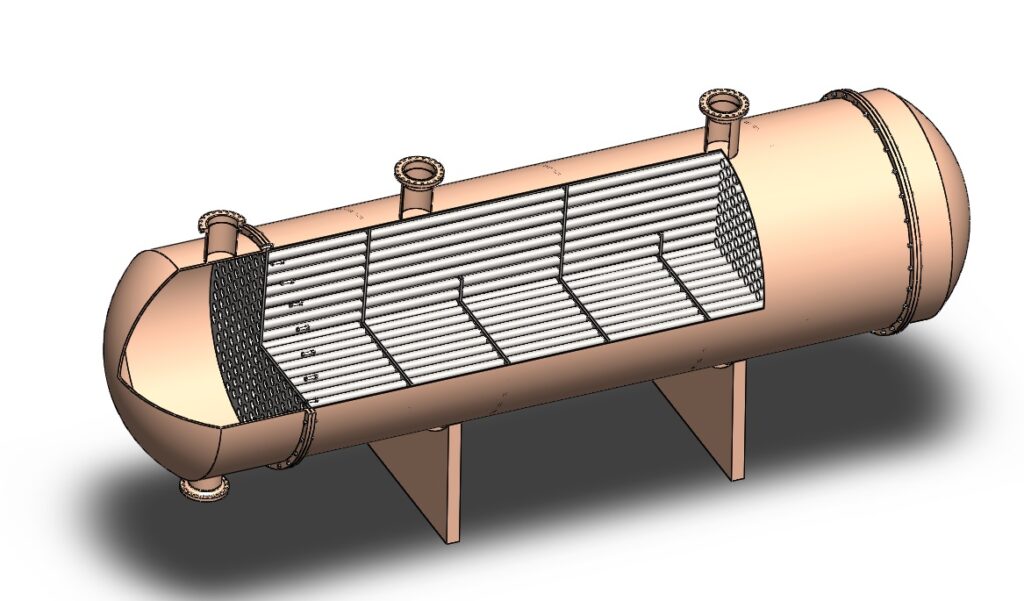

An ORC power plant consists of several key components:

- Heat Exchanger (Evaporator): The heat source is used to heat the working fluid in an evaporator. The working fluid absorbs the heat, causing it to vaporize and turn into high-pressure vapor. Unlike traditional steam-based systems, ORC plants use organic fluids with low boiling points, which allows them to operate at lower temperatures and pressures.

- Turbine: The high-pressure vapor from the evaporator enters the turbine. As it expands in the turbine, it causes the turbine blades to spin, converting the thermal energy of the vapor into mechanical energy. This mechanical energy is then used to drive a generator, which produces electricity.

- Condenser: After passing through the turbine, the vapor is cooled and condensed back into liquid form in a condenser. The condenser uses a cooling medium such as air, water, or a cooling tower to remove heat from the vapor, causing it to revert to its liquid phase.

- Pump: The liquid working fluid is then pumped from the condenser to the evaporator. The pump increases the pressure of the fluid, which is necessary for it to circulate through the cycle and absorb heat in the evaporator.

- Generator: The turbine is connected to a generator, which converts the mechanical energy into electricity. The generator produces a steady supply of electrical power, which can then be used to supply local needs or be fed into the grid.

Operational Process of an ORC Power Plant

- Heat Transfer to Working Fluid: The working fluid, typically an organic refrigerant such as R245fa, n-pentane, or other low-boiling-point substances, absorbs heat from the heat source in the evaporator. As the fluid absorbs the heat, it evaporates into a high-pressure vapor.

- Turbine Expansion: This high-pressure vapor is directed to the turbine. As the vapor expands in the turbine, it loses pressure, which drives the turbine blades, converting the thermal energy of the vapor into mechanical energy.

- Condensation: After passing through the turbine, the vapor enters the condenser, where it is cooled by a secondary fluid (usually water or air). The cooling process causes the vapor to condense back into a liquid state.

- Recirculation: The condensed liquid is pumped back into the evaporator, where it will once again absorb heat and vaporize, continuing the cycle.

Applications of ORC Power Plants

- Geothermal Power: In regions with geothermal energy resources, ORC power plants can tap into low-temperature geothermal resources, converting them into electricity. ORC plants are ideal for low-enthalpy geothermal reservoirs, where temperatures are too low for conventional steam turbines.

- Waste Heat Recovery: ORC power plants can be used to recover waste heat from industrial processes. For example, industries such as cement production, steel manufacturing, or chemical plants often generate significant amounts of waste heat that can be captured and used to generate electricity via an ORC system. This not only improves the efficiency of the process but also reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

- Biomass and Combined Heat and Power (CHP): Biomass power plants that burn organic materials like wood chips can use ORC systems to convert thermal energy into electricity. In CHP applications, the waste heat from the power generation process can also be used for district heating or industrial processes.

- Solar Thermal: CSP plants, which focus sunlight to generate high temperatures, can integrate ORC technology to efficiently convert solar energy into electricity, especially when coupled with thermal storage systems that allow for energy production even when the sun isn’t shining.

- District Heating: In some applications, ORC systems are paired with district heating networks, using excess heat to generate electricity while supplying heat to residential or commercial buildings.

Advantages of ORC Power Plants

- Efficiency at Low Temperatures: ORC systems are designed to operate at much lower temperatures than traditional steam-based Rankine cycles, making them ideal for applications involving low-grade heat sources.

- Lower Environmental Impact: ORC systems allow for the efficient conversion of waste heat into electricity, reducing emissions and improving overall energy efficiency. This can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of industrial processes and power plants.

- Compact and Modular: ORC plants are often smaller and more compact than traditional Rankine cycle systems, making them well-suited for small-scale power generation, such as decentralized energy production or remote areas where grid connection is not feasible.

- Scalability: ORC plants can be scaled to meet a wide range of energy needs, from small installations generating a few kilowatts to larger plants capable of producing several megawatts.

- Flexibility: The organic fluid used in ORC systems can be chosen based on the specific heat source and application, allowing for optimization of performance in diverse environments.

Challenges and Limitations

- Upfront Costs: While ORC plants offer many advantages, they can be expensive to set up, particularly in terms of the cost of purchasing and installing the necessary components.

- Heat Source Dependency: ORC systems rely on a consistent heat source. In applications like industrial waste heat recovery, the availability and temperature of waste heat may fluctuate, which can affect the performance of the ORC system.

- System Complexity: While ORC systems are simpler than conventional steam-based turbines, they still require careful design, especially when integrating with heat recovery or renewable energy systems. Components such as heat exchangers, turbines, and condensers need to be optimized to handle the specific working fluid and temperature conditions.

Conclusion

An ORC power plant offers a promising solution for converting low-temperature heat into electricity, with applications across a wide range of industries and renewable energy sources. Its ability to utilize low-grade heat makes it a key technology in waste heat recovery, geothermal power, biomass, and solar thermal applications. Despite its higher initial costs and reliance on a steady heat source, the advantages of increased energy efficiency, reduced emissions, and scalability make the ORC power plant a valuable asset in the transition to cleaner and more efficient energy systems.

An ORC (Organic Rankine Cycle) power plant harnesses low-grade heat sources to generate electricity. This type of plant is designed to operate efficiently with heat sources that would be too low in temperature for traditional steam-based Rankine cycles, making it a suitable option for geothermal energy, industrial waste heat, solar thermal energy, and biomass applications. The core principle of an ORC power plant is the use of an organic working fluid, typically with a low boiling point, allowing it to vaporize at lower temperatures compared to water, which is the working fluid in conventional Rankine cycles.

In an ORC power plant, the heat from a source like geothermal water or industrial waste heat is transferred to the organic fluid through a heat exchanger. The fluid absorbs this heat, vaporizes, and becomes a high-pressure vapor. This vapor is directed to a turbine, where it expands and drives a generator to produce electricity. After passing through the turbine, the vapor enters a condenser, where it is cooled and returns to its liquid form, losing the heat that was initially absorbed. The liquid is then pumped back to the heat exchanger to begin the process again. This cycle repeats continuously, converting thermal energy into mechanical energy, which is then transformed into electricity by the generator.

One of the key benefits of ORC power plants is their ability to utilize low-temperature heat, typically in the range of 80°C to 300°C, which makes them suitable for applications where traditional power generation technologies, such as steam turbines, are less effective. This allows for energy recovery from sources like industrial waste heat, which would otherwise be released into the environment without generating power, or geothermal resources that are not hot enough for conventional geothermal power plants. Similarly, ORC systems can be used in biomass power generation, where the combustion of organic materials like wood chips or agricultural waste produces heat that can be converted into electricity.

In addition to their use in industrial and renewable energy applications, ORC power plants are also well-suited for use in concentrated solar power (CSP) systems. In CSP, mirrors or lenses focus sunlight to generate high temperatures, and an ORC system can efficiently convert this thermal energy into electricity. Because of their relatively low operating temperatures, ORC plants can capture and convert energy from CSP systems more effectively than traditional steam turbines.

ORC power plants are generally more compact than traditional Rankine cycle plants, making them an attractive option for small-scale power generation or decentralized energy systems. Their smaller footprint also makes them well-suited for locations with limited space or in remote areas where grid connection may be difficult. The systems are also scalable, so they can be designed to meet a wide range of energy needs, from small installations that generate a few kilowatts to larger plants capable of producing several megawatts of power.

The economic benefits of ORC plants stem from their ability to recover waste heat and convert it into electricity, improving the energy efficiency of industrial processes and reducing operational costs. In industries that generate significant amounts of waste heat, such as cement production, steel manufacturing, or chemical plants, ORC systems can provide a continuous and reliable power source while reducing the carbon footprint of these operations. Similarly, by utilizing renewable resources like biomass or geothermal energy, ORC systems can help reduce reliance on fossil fuels and contribute to cleaner energy production.

However, there are some challenges associated with ORC power plants. The initial investment costs can be relatively high, as the system requires specialized components like turbines, heat exchangers, and pumps that are designed to handle the specific organic fluids used in the cycle. Additionally, the performance of ORC systems can be influenced by the temperature and availability of the heat source, which may fluctuate, particularly in industrial waste heat recovery applications. Furthermore, while ORC systems are generally simpler and more efficient than steam-based systems at lower temperatures, they still require careful design and optimization to achieve maximum performance.

Despite these challenges, ORC technology continues to advance, with improvements in fluid selection, turbine efficiency, and system integration making ORC power plants more cost-effective and versatile. Ongoing research into new organic fluids that have lower environmental impact and improved thermodynamic properties will continue to enhance the efficiency of these systems. The global push for renewable energy and the growing need for energy efficiency are likely to drive further adoption of ORC technology, particularly in industries that generate waste heat or in regions where access to high-temperature heat sources is limited.

In conclusion, ORC power plants offer an effective and sustainable solution for converting low-temperature heat into electricity. Their ability to utilize a wide range of heat sources, including geothermal, industrial waste heat, biomass, and solar thermal energy, makes them a valuable technology in the transition to cleaner and more efficient energy systems. While challenges remain, particularly regarding initial costs and system optimization, the advantages of ORC plants—such as their efficiency at low temperatures, compact design, and versatility—make them an important component of the future energy landscape.

As ORC technology continues to develop, its role in global energy production is becoming increasingly important, particularly in the context of a growing demand for sustainable energy solutions. Beyond its efficiency at converting low-grade heat into electricity, the ORC system also offers opportunities to enhance the overall sustainability of energy systems in several key ways.

One significant advantage is that ORC plants can operate in distributed energy systems. These systems, which generate power at or near the point of use, are becoming more common as part of the shift away from centralized, large-scale power generation. Small ORC power plants can be deployed in a variety of settings, such as industrial sites, remote communities, or even urban areas, where they can make use of available waste heat, geothermal resources, or other renewable heat sources to produce electricity on-site. This decentralization helps to reduce transmission losses associated with long-distance power transmission, thereby increasing the overall efficiency of the energy grid.

In terms of environmental benefits, ORC systems contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by recovering waste heat and turning it into useful electricity instead of allowing it to escape into the environment. By utilizing biomass or geothermal heat, ORC plants also help reduce reliance on fossil fuels, which are major contributors to climate change. The use of organic fluids in ORC systems further minimizes environmental impact, especially as new, more eco-friendly fluids continue to be developed. Advances in fluid technology have allowed for the replacement of higher global warming potential (GWP) fluids with ones that have a significantly lower environmental impact, thus improving the overall sustainability of ORC-based power plants.

Moreover, ORC technology is also being explored for its potential in hybrid energy systems. For instance, ORC plants can be integrated with solar or wind energy systems to provide a more stable and reliable power supply. Solar energy, for example, is intermittent, meaning that it only generates electricity when sunlight is available. However, when paired with ORC technology, excess heat from concentrated solar power (CSP) systems can be stored and used to generate electricity even when the sun isn’t shining. This hybrid approach allows for greater energy security and grid stability by balancing renewable energy supply with a backup source of power from waste heat or stored energy.

In industrial settings, ORC plants provide a pathway to greater energy independence and cost savings. Many industrial processes generate substantial amounts of waste heat, and by capturing and converting this heat into electricity, companies can reduce their reliance on external electricity supplies, lowering energy costs over the long term. Furthermore, the electricity generated by ORC systems can be used internally to power the production process, making the entire system more self-sufficient. Industries that require continuous, high-temperature operations—such as cement, glass, and steel production—stand to benefit significantly from integrating ORC systems into their processes.

Despite these advantages, one of the challenges for wider adoption of ORC power plants is the optimization of the entire system to handle various types of heat sources and varying load conditions. The performance of ORC plants is directly influenced by the temperature and quality of the heat source, and in some cases, these conditions can be variable. For instance, in industrial applications where waste heat is recovered, fluctuations in production cycles can cause changes in the heat availability, potentially reducing the efficiency of the ORC system. To address this, ORC systems are increasingly being designed with more advanced control systems and energy storage solutions that can help manage these variations and improve performance under changing conditions.

Additionally, while ORC systems are becoming more cost-competitive, the initial capital investment required for installation can still be a barrier for some applications, particularly smaller-scale projects or those with less consistent heat sources. However, as the technology matures and economies of scale come into play, the cost of ORC systems is expected to decrease, making them more accessible to a wider range of industries and applications. Incentives and subsidies for renewable energy projects, as well as the growing focus on energy efficiency, may further drive adoption by making ORC systems more financially viable.

Another consideration is the ongoing research and development efforts to improve ORC performance. These efforts are focused on increasing the efficiency of heat exchangers, optimizing the design of turbines, and refining the selection of working fluids. Improvements in material science, such as the development of more durable and heat-resistant materials, also play a critical role in extending the lifespan and efficiency of ORC components. As these technologies continue to improve, the overall performance and economic feasibility of ORC power plants will only increase.

The long-term outlook for ORC power plants is positive, driven by both technological advancements and the increasing need for clean, efficient energy solutions. The combination of ORC’s ability to utilize low-temperature heat and its adaptability to various energy sources makes it an attractive option for a wide array of applications. Whether for industrial waste heat recovery, geothermal power, biomass, or solar thermal systems, ORC plants are helping to drive the transition toward a more sustainable energy future.

Looking further into the future, ORC technology may also play a key role in the development of new, decentralized energy systems that are more resilient and adaptable to climate change. As global energy infrastructure becomes increasingly decentralized, with local and regional energy systems playing a larger role, ORC systems could be integral in ensuring a reliable and stable energy supply. The ability to generate power locally, from a variety of heat sources, could provide communities with greater energy security and resilience in the face of disruptions caused by climate change, natural disasters, or geopolitical instability.

In conclusion, the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) power plant is a versatile and sustainable technology that continues to evolve, offering the potential to transform the way we generate and utilize energy. By tapping into low-temperature heat sources, ORC plants provide a unique solution for generating electricity from waste heat, geothermal resources, biomass, and solar thermal energy. As technology advances, ORC systems will become even more efficient, cost-effective, and widely adopted, contributing to a cleaner, more energy-efficient future. Whether integrated with renewable energy sources or used in industrial applications, ORC technology offers significant promise in reducing carbon emissions, improving energy efficiency, and enabling more sustainable energy systems worldwide.

As ORC technology continues to evolve, new trends and innovations are emerging that could expand its applications and improve its efficiency. One of the most exciting developments in the field of ORC systems is the integration with energy storage solutions. Combining ORC power plants with thermal energy storage can help address the intermittent nature of many renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind. This hybrid approach allows excess thermal energy generated during peak production times to be stored and used later, ensuring a continuous supply of electricity even when renewable sources are not available. By integrating ORC systems with energy storage technologies like molten salt, phase-change materials, or other advanced thermal storage systems, energy production becomes more flexible and reliable.

Another promising avenue for improving ORC systems is the use of advanced heat exchangers. Heat exchangers play a crucial role in the efficiency of the ORC cycle, as they are responsible for transferring heat from the source to the organic fluid without significant energy loss. New designs, such as compact, plate-fin heat exchangers, can help maximize heat transfer efficiency while reducing the overall size and cost of the system. The development of more efficient heat exchangers is particularly important for industrial applications, where large volumes of waste heat need to be captured and converted into electricity.

In addition to heat exchangers, innovations in turbine technology are also improving ORC systems. Researchers are focusing on enhancing the performance of turbines used in ORC plants by optimizing their design for the specific organic fluids used in the cycle. For example, micro-turbines and axial turbines designed for ORC applications offer the potential to improve efficiency while minimizing mechanical wear. Additionally, the use of variable-speed turbines could help adjust the power output in response to fluctuating heat input, improving overall system performance and making ORC plants more adaptable to changing operational conditions.

As the demand for renewable energy and energy efficiency grows, ORC power plants are increasingly being seen as a solution for hybrid power generation systems that combine multiple energy sources. One such example is the combination of ORC systems with biomass boilers or waste-to-energy plants. This combination enables the ORC plant to use heat generated from the combustion of organic materials to produce electricity. With growing concerns over waste disposal and the need to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, ORC plants paired with biomass or waste-to-energy systems could help provide a more sustainable solution for managing waste while generating renewable energy.

Another area of development is the optimization of organic fluids used in the ORC cycle. The working fluid in an ORC system plays a critical role in determining the system’s efficiency, operating range, and environmental impact. Research is ongoing to identify new organic fluids that offer better thermodynamic properties, lower environmental impacts, and greater compatibility with different heat sources. For example, new refrigerants that are less harmful to the environment and have lower global warming potential (GWP) are being developed. The use of these next-generation fluids will not only improve the efficiency of ORC systems but also help reduce their carbon footprint and make them even more sustainable in the long run.

The adoption of ORC systems is also being facilitated by growing government support for renewable energy projects. Many countries have introduced incentives, subsidies, and policies to encourage the development and deployment of renewable energy technologies, including ORC power plants. These incentives make ORC systems more financially viable, particularly in sectors like industrial waste heat recovery, where the payback period for an ORC system can be relatively short. Governments are also providing funding for research and development to improve ORC technology, making it more affordable and efficient. In addition, carbon pricing and emissions reduction goals are driving industries to adopt cleaner technologies, including ORC systems, as a way to reduce their environmental impact and meet regulatory requirements.

Furthermore, the growing trend toward sustainable and energy-efficient buildings is increasing the demand for ORC systems in the construction and real estate sectors. ORC plants can be used in combined heat and power (CHP) systems to provide both electricity and heating for buildings. In district heating systems, ORC technology can help recover waste heat from nearby industrial processes, turning it into electricity and improving the overall energy efficiency of urban areas. This makes ORC systems an attractive option for developers looking to create energy-efficient, low-carbon buildings and neighborhoods.

The expansion of the ORC market is not limited to traditional power generation and industrial applications. In remote or off-grid locations, ORC systems offer a reliable source of electricity by utilizing local heat sources such as geothermal wells, biomass, or even concentrated solar power. These systems can provide a decentralized energy solution that is particularly useful for rural communities, small industries, or remote research stations. ORC plants are already being deployed in such locations, helping to bring clean, renewable power to areas that might otherwise rely on diesel generators or other less sustainable energy sources.

The future of ORC power plants is also being shaped by their potential role in the global transition to a circular economy. In a circular economy, materials and resources are reused, and waste is minimized. ORC systems can contribute to this model by recovering waste heat from industrial processes and converting it into electricity, thus reducing the need for additional energy inputs and minimizing waste. By enabling industries to extract value from waste heat, ORC systems help close the loop in energy-intensive sectors and promote more sustainable industrial practices.

Looking ahead, ORC power plants will continue to play a crucial role in the global energy landscape. As the world increasingly shifts toward renewable energy and energy efficiency, ORC systems offer a flexible and cost-effective solution for harnessing low-temperature heat and turning it into valuable electricity. Their ability to integrate with various energy sources, improve energy efficiency, and reduce emissions positions them as a key technology in addressing the challenges of climate change and the need for sustainable development.

In conclusion, the ongoing advancements in ORC technology, coupled with the growing demand for clean, efficient energy, suggest a bright future for ORC power plants. As they evolve, these systems will continue to offer new opportunities for integrating renewable energy, recovering waste heat, and providing distributed energy solutions. Whether used in industrial applications, renewable energy projects, or off-grid power generation, ORC systems are becoming an integral part of the transition to a more sustainable, low-carbon energy future.

Micro Orc Generator

A micro ORC (Organic Rankine Cycle) generator is a small-scale version of a traditional ORC power plant, designed to convert low-grade waste heat into electricity in compact and efficient systems. These generators are typically used for power generation in smaller, decentralized applications, making them an ideal solution for industries, remote locations, and off-grid systems where electricity demand is relatively low.

Key Features of Micro ORC Generators:

- Size and Scalability: Micro ORC generators are designed to be small and modular, with power outputs typically ranging from a few kilowatts (kW) to around 100 kW. This makes them suitable for applications like small industrial sites, remote communities, or for backup power in off-grid systems. The compact nature of these generators allows them to be installed in spaces where traditional power generation systems would be impractical.

- Energy Source: These systems utilize low-temperature heat sources that are generally not efficient for conventional power generation. Typical heat sources include industrial waste heat (from processes like cement production, steel manufacturing, and chemical processing), geothermal energy, biomass, or even heat recovered from vehicle engines or solar thermal systems. The micro ORC system captures this heat, converts it into electricity, and helps reduce energy costs.

- Organic Working Fluid: Like larger ORC systems, micro ORC generators use organic fluids with lower boiling points compared to water. These fluids allow the cycle to operate at lower temperatures (typically in the range of 80°C to 300°C), making them ideal for recovering waste heat or utilizing renewable heat sources. The specific fluid used depends on the operating conditions and the heat source.

- Efficiency: Micro ORC generators are highly efficient for converting low-temperature heat into electricity. Although the efficiency of any ORC system is lower than that of traditional high-temperature systems (such as steam turbines), the advantage of micro ORC is its ability to use heat sources that would otherwise go to waste. The efficiency can vary depending on the temperature of the heat source and the specific design of the system, but modern micro ORC generators can achieve efficiencies of 10-20%.

- Applications: Micro ORC generators are used in a variety of applications, including:

- Industrial waste heat recovery: Micro ORCs are used to capture heat from industrial processes and convert it into electricity, helping companies reduce their reliance on grid power and lower operational costs.

- Remote/off-grid power generation: In off-grid locations, where conventional power grids are not available, micro ORC systems can provide reliable electricity by using locally available heat sources like biomass, waste heat, or geothermal.

- Backup power: Micro ORC generators can serve as backup power in places where a consistent electricity supply is needed but is not always available from the grid, such as in remote facilities or on islands.

- Renewable energy systems: Micro ORC technology can be integrated with renewable energy sources like concentrated solar power (CSP) to create hybrid systems that generate electricity from both thermal energy and solar power.

- Environmental Benefits: Micro ORC systems contribute to sustainability by recovering otherwise wasted energy and converting it into useful electricity. This reduces the consumption of fossil fuels, lowers greenhouse gas emissions, and improves overall energy efficiency. Additionally, the organic fluids used in micro ORC systems are designed to be more environmentally friendly compared to traditional refrigerants used in other thermal systems.

- Cost and Economic Feasibility: The initial cost of micro ORC generators can be a barrier for some users, as they require specialized components like turbines, heat exchangers, and pumps to handle the organic working fluids. However, the long-term economic benefits of reduced energy costs and increased energy efficiency can offset the upfront investment. The payback period depends on the amount of waste heat available, energy prices, and the scale of the system. For industries with abundant waste heat, the payback period can be relatively short.

Advantages of Micro ORC Generators:

- Flexibility: Micro ORC systems can be adapted to a wide variety of heat sources, including industrial waste, geothermal, solar, and biomass, making them highly versatile.

- Energy Recovery: They help recover heat that would otherwise be wasted, improving the overall energy efficiency of industrial and commercial processes.

- Reduced Environmental Impact: By converting waste heat into electricity, micro ORC systems reduce the need for external electricity, which may be generated from fossil fuels, thus decreasing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Decentralized Power: Micro ORC generators enable decentralized, on-site power generation, which can be a more reliable and cost-effective solution for remote or off-grid applications.

Challenges and Considerations:

- Capital Cost: The initial investment for a micro ORC system can be significant, although costs are coming down as technology advances and production scales up.

- Variable Heat Source: The performance of micro ORC generators depends on the availability and temperature of the heat source, which may fluctuate, especially in industrial waste heat recovery applications. The system needs to be designed to handle these variations effectively.

- Maintenance and Reliability: Although micro ORC systems are relatively low-maintenance, the specialized components—such as turbines and heat exchangers—require regular checks and servicing to ensure long-term reliability and optimal performance.

Future Outlook:

As the demand for energy efficiency and clean energy solutions increases, the role of micro ORC generators is expected to grow. Research and development efforts are focusing on improving system efficiency, reducing costs, and expanding the range of heat sources that can be used. In particular, advances in working fluids, turbine technology, and heat exchanger designs are expected to make micro ORC systems even more efficient and cost-effective. Furthermore, the integration of micro ORC generators with renewable energy systems like solar and biomass could open new opportunities for decentralized, clean energy production.

In conclusion, micro ORC generators offer a promising solution for utilizing waste heat and renewable energy sources to generate electricity in smaller-scale applications. Their versatility, efficiency, and environmental benefits make them an attractive option for industries, remote locations, and off-grid power systems. With ongoing technological improvements, micro ORC systems have the potential to become an increasingly important component of the global energy mix.

Micro ORC generators are becoming an increasingly popular solution for converting low-grade heat into electricity in a wide range of small-scale applications. Their flexibility and efficiency make them ideal for capturing energy that would otherwise go to waste, especially in industries and locations that generate excess heat as a byproduct of their processes. These generators are highly adaptable, capable of utilizing various heat sources such as industrial waste heat, geothermal energy, biomass, and even concentrated solar power.

One of the key benefits of micro ORC generators is their ability to provide localized power generation. This decentralized approach reduces the reliance on the electrical grid, which can be especially beneficial in remote or off-grid locations where access to conventional power infrastructure is limited or unreliable. For example, in rural areas, islands, or isolated industrial plants, micro ORC systems can be used to provide continuous and reliable electricity by tapping into locally available heat sources. This not only ensures energy security but also helps reduce the cost of electricity by minimizing transmission losses and dependency on imported fuels.

Micro ORC systems also provide a sustainable solution to the challenge of waste heat management. Industries such as cement, steel, glass manufacturing, and chemical production typically generate significant amounts of waste heat during their operations. Without recovery, this heat is often released into the environment, contributing to wasted energy and potential environmental harm. Micro ORC generators enable these industries to capture and convert this heat into useful electricity, reducing their reliance on external energy sources and improving overall operational efficiency. Over time, the energy recovered can offset a portion of the operational costs, leading to cost savings and a faster return on investment.

The environmental benefits of micro ORC systems are significant. By utilizing waste heat and renewable energy sources like biomass and geothermal, they help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, supporting the transition to a more sustainable energy landscape. Micro ORC systems also reduce the need for fossil fuel-based electricity generation, further minimizing environmental impact. Additionally, the use of organic fluids in ORC cycles, which have lower boiling points compared to water, ensures that the systems can operate efficiently at lower temperatures. This makes them particularly effective at harnessing energy from sources that are otherwise underutilized by traditional power generation technologies.

Despite the advantages, micro ORC generators face certain challenges. The initial cost of these systems can be a barrier to widespread adoption, particularly for smaller businesses or industries with limited budgets. The technology requires specialized components, such as turbines, heat exchangers, and pumps, which can be expensive. However, the cost of micro ORC systems is expected to decrease as technology improves and the market for these systems grows, driven by the increasing demand for energy efficiency and sustainable power solutions.

Another challenge is the variability of the heat source. In industrial applications, waste heat can fluctuate depending on production schedules and operational conditions. This variation can affect the performance of the micro ORC system. To address this, modern systems are being designed with more advanced control mechanisms and energy storage solutions that help balance fluctuations in heat availability. These systems ensure that the micro ORC generator can continue to operate efficiently, even when the heat source is not constant.

Looking forward, advancements in technology will likely make micro ORC systems even more effective and cost-efficient. Research into new organic fluids with better thermodynamic properties, along with improved turbine and heat exchanger designs, will continue to enhance the performance of micro ORC generators. As the demand for renewable energy grows, these systems could become an integral part of hybrid power generation solutions, where they are combined with solar, wind, or other renewable sources to provide a more reliable and stable power supply.

The potential for micro ORC generators extends beyond industrial applications. They can also be utilized in small-scale residential or commercial energy systems, where they could complement renewable energy technologies. In combination with solar thermal or geothermal systems, micro ORC generators could provide a continuous and reliable source of electricity, reducing energy costs and enhancing the overall sustainability of buildings and communities.

In conclusion, micro ORC generators offer a promising and sustainable solution for generating electricity from low-grade heat. Their ability to recover waste heat and convert it into useful energy makes them valuable for industries, remote locations, and off-grid systems. As technology advances and costs decrease, micro ORC systems are likely to become an increasingly viable option for small-scale power generation, contributing to a cleaner, more efficient energy future.

As the technology behind micro ORC generators continues to evolve, their potential applications are expanding into new areas. For instance, the integration of micro ORC systems with emerging technologies such as smart grids and Internet of Things (IoT) systems is opening up new possibilities. In smart grid applications, micro ORC generators can be part of a decentralized, distributed energy system, where small power generators supply energy locally, reduce strain on the central grid, and enhance energy security. By connecting these systems to smart meters and IoT devices, operators can monitor real-time performance, adjust operations dynamically, and ensure efficient energy distribution and usage.

In remote regions or off-grid environments, micro ORC systems can be further optimized by coupling them with battery storage systems. This combination enables excess energy generated during periods of high heat availability to be stored and used when the heat source is not present, such as at night or during fluctuating industrial operations. The ability to store energy for later use not only improves the reliability of the power supply but also enhances the overall efficiency of the micro ORC system.

In the transportation sector, there is growing interest in integrating micro ORC technology with electric vehicles (EVs), especially in hybrid or plug-in hybrid vehicles. In these applications, micro ORC generators could recover heat generated by the engine or exhaust system and convert it into electricity to recharge the vehicle’s battery. This would increase the vehicle’s energy efficiency and range while reducing the reliance on external charging infrastructure. This application of micro ORC systems in the automotive industry could contribute to the development of more sustainable transportation options.

Micro ORC technology also has a promising future in the field of district heating and cooling systems. These systems, which provide centralized heating and cooling to a community or large building complex, can integrate micro ORC generators to harness waste heat and generate electricity, reducing the overall energy consumption of the system. By using micro ORC generators to convert excess heat into electricity, the system becomes more energy-efficient, helping to lower operating costs and reducing the environmental impact of heating and cooling operations.

The ability of micro ORC generators to work efficiently with low-temperature heat sources has led to a growing interest in their use alongside solar thermal and concentrated solar power (CSP) systems. In solar thermal applications, micro ORC systems can convert the heat captured by solar collectors into electricity, enabling continuous power generation even when the sun is not shining. Similarly, CSP systems that use mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight and generate heat can be paired with micro ORC generators to enhance their energy production. This synergy between solar technologies and micro ORC systems could increase the overall efficiency of solar power plants and provide a more consistent and reliable energy source.

The growth of the biogas and waste-to-energy industries also presents opportunities for micro ORC generators. By converting biogas from agricultural waste, landfills, or wastewater treatment plants into electricity, micro ORC systems can contribute to the development of circular economy solutions that reduce waste, lower emissions, and generate clean energy. The ability to generate power from organic waste and waste heat allows industries and municipalities to turn previously discarded materials into valuable resources, contributing to environmental sustainability.

Moreover, micro ORC generators are also well-suited for use in remote research stations or military installations, where reliable, off-grid power generation is essential. In these situations, micro ORC systems can provide a stable and sustainable power supply, utilizing locally available waste heat or renewable resources to generate electricity. This is particularly important in harsh environments, such as arctic regions, where access to the grid is non-existent or unreliable. The ability to operate autonomously and efficiently is a significant advantage in such remote and critical applications.

Despite the wide range of promising applications, the continued adoption of micro ORC systems will depend on overcoming certain technical and economic challenges. One of the key factors influencing their widespread deployment is the cost of integration, which includes both the initial capital investment and the ongoing maintenance. While micro ORC technology is becoming more affordable as manufacturing processes improve and production scales up, the high upfront cost for small-scale systems still poses a hurdle for some potential users, particularly in developing regions or small businesses. However, with increasing support for renewable energy technologies and energy efficiency, government incentives and subsidies could play a significant role in making micro ORC systems more accessible.

The ongoing research into optimizing working fluids and turbine technology is also crucial to improving the performance of micro ORC generators. As new materials and fluids are developed, the efficiency of the systems can be further enhanced, reducing operational costs and expanding the range of heat sources that can be effectively used. Additionally, innovations in heat exchanger designs and advanced control systems will make these systems more efficient and responsive to fluctuations in heat input, which is especially important in dynamic industrial environments.

In terms of scalability, micro ORC systems can be expanded or combined with other energy generation technologies to meet varying power needs. For example, small-scale micro ORC generators can be clustered together in a modular fashion, increasing their output as demand grows. This scalability allows micro ORC systems to serve a broad range of applications, from small-scale residential needs to large industrial operations.

As awareness of the importance of energy efficiency, waste heat recovery, and sustainable energy solutions grows, micro ORC technology will continue to gain traction. Their ability to provide low-carbon electricity from low-temperature heat sources, their adaptability to different applications, and the growing demand for energy-efficient solutions make them an attractive option for businesses and communities seeking to reduce energy costs and minimize their environmental impact.

In summary, the future of micro ORC generators is promising, driven by ongoing technological advancements, a growing focus on energy efficiency, and increasing support for renewable and decentralized energy systems. Their ability to recover waste heat and generate electricity in a wide range of applications—from industrial processes to remote off-grid systems—positions them as a key player in the transition to a more sustainable energy future. As the technology matures, micro ORC generators will likely become more affordable, efficient, and widely deployed, further contributing to the global push for clean and renewable energy solutions.

As micro ORC generators continue to evolve, there is growing interest in their potential for contributing to the global energy transition. With the push toward decarbonizing energy production and improving energy efficiency, micro ORC systems provide a solution that can complement a variety of renewable energy sources. In particular, the ability to harness low-temperature heat from a wide range of sources makes micro ORC technology especially valuable in the context of the circular economy, where the goal is to minimize waste, optimize resource usage, and reduce environmental impact.

One area where micro ORC systems are likely to play a pivotal role is in industrial decarbonization. Many industries, such as cement, steel, and chemical manufacturing, produce vast amounts of waste heat. By recovering and converting this waste heat into electricity through micro ORC systems, industries can reduce their reliance on grid electricity, lower energy costs, and contribute to emissions reduction. This shift not only helps businesses meet increasing regulatory pressure to cut carbon emissions but also improves the overall efficiency of their operations. Moreover, micro ORC systems enable industries to become more energy independent by utilizing locally available waste heat or renewable sources, further reducing their carbon footprint.

Micro ORC technology is also poised to make a significant impact in developing countries, where access to electricity is still limited in rural and remote areas. In these regions, micro ORC generators can provide a reliable and cost-effective solution for off-grid power generation. Utilizing locally available waste heat from biomass, solar thermal systems, or even waste-to-energy processes, micro ORCs can deliver clean and affordable electricity where it is needed most. This decentralization of energy production helps reduce the need for expensive grid infrastructure and can improve the livelihoods of people living in remote communities. Additionally, micro ORC systems can contribute to local economic development by providing power for small businesses, healthcare facilities, schools, and agricultural operations.

The integration of micro ORC systems with advanced digital technologies is also expected to drive further advancements. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning can help optimize the performance of micro ORC systems by predicting and adapting to fluctuations in heat availability, improving energy recovery, and reducing downtime. Predictive maintenance algorithms can monitor the health of key system components, such as turbines and heat exchangers, identifying issues before they lead to costly repairs. This integration can significantly improve the reliability and longevity of micro ORC systems, making them even more attractive for industries and remote applications.

One of the key areas of innovation in micro ORC technology is the development of hybrid systems. These systems combine micro ORC technology with other renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind, to enhance overall efficiency and energy production. For example, in regions with high solar radiation, a micro ORC system can work alongside a solar thermal system, converting excess heat during the day into electricity. Similarly, micro ORCs can be integrated with biomass or waste-to-energy systems, where the heat generated by combustion processes can be captured and used for power generation. Hybrid systems offer a more continuous and stable power supply by balancing intermittent energy sources like solar and wind with the consistent heat supply that micro ORC systems can use.

As the world moves toward smart cities, micro ORC generators will be part of a broader effort to create energy-efficient, low-carbon urban environments. In smart cities, waste heat recovery and decentralized power generation will become integral components of energy management systems. Micro ORC systems, when integrated with building management systems or district energy networks, can help optimize energy use by recovering waste heat from buildings, industrial processes, or even urban transportation systems, such as buses or trains. In this context, micro ORC systems are seen as a solution that can help cities meet their sustainability goals while improving the resilience of urban infrastructure.

The integration of energy storage with micro ORC systems is another promising development. By combining micro ORC generators with thermal energy storage or battery storage technologies, excess heat energy can be stored for later use, ensuring a more consistent power supply. This is particularly useful in applications where the heat source is variable or intermittent, such as waste heat from industrial processes that may fluctuate depending on production schedules. Energy storage also enables micro ORC systems to supply power during periods when the heat source is not available, further improving their versatility and reliability.

Furthermore, the circular economy model can be enhanced by integrating micro ORC technology with waste recycling and resource recovery systems. In municipal waste management, for instance, micro ORC systems can be used to capture the heat generated during the incineration of waste materials and convert it into electricity. This not only helps generate clean energy from waste but also reduces the need for landfill space and lowers the environmental impact of waste disposal. Micro ORC systems, therefore, offer an efficient way to close the loop in waste management, contributing to a more sustainable approach to urban development.

The financial viability of micro ORC systems is expected to improve as the technology matures and market demand grows. Advances in manufacturing techniques, system design, and economies of scale will reduce the cost of these systems, making them more accessible to a wider range of users. Additionally, the availability of government incentives, subsidies, and carbon credit programs for renewable energy technologies will further incentivize the adoption of micro ORC systems, particularly in sectors that generate substantial amounts of waste heat. As more industries and communities realize the benefits of waste heat recovery and decentralized energy production, the global market for micro ORC generators will likely expand.

Public awareness and policy support are crucial to the broader adoption of micro ORC systems. Governments and policymakers play a key role in creating favorable conditions for the development and deployment of these systems. By introducing regulations that encourage energy efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, and support the use of renewable energy, governments can help drive the adoption of micro ORC technology across industries and communities. Public awareness campaigns can also educate businesses, industries, and consumers about the benefits of micro ORC systems, from energy savings to environmental impact reduction.

In conclusion, micro ORC generators represent a promising technology for recovering waste heat and converting it into clean, reliable electricity. As the demand for energy efficiency, renewable energy, and sustainability grows, micro ORC systems are likely to play an increasingly important role in industries, remote locations, and off-grid applications. With ongoing technological advancements, cost reductions, and growing support for renewable energy solutions, micro ORC generators will become more widely adopted, helping to create a more sustainable, decentralized, and energy-efficient future. As part of the broader energy transition, micro ORC technology will continue to drive innovation, improve energy efficiency, and contribute to global efforts to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change.

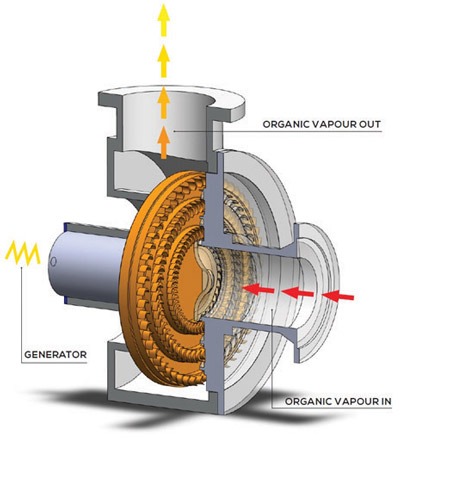

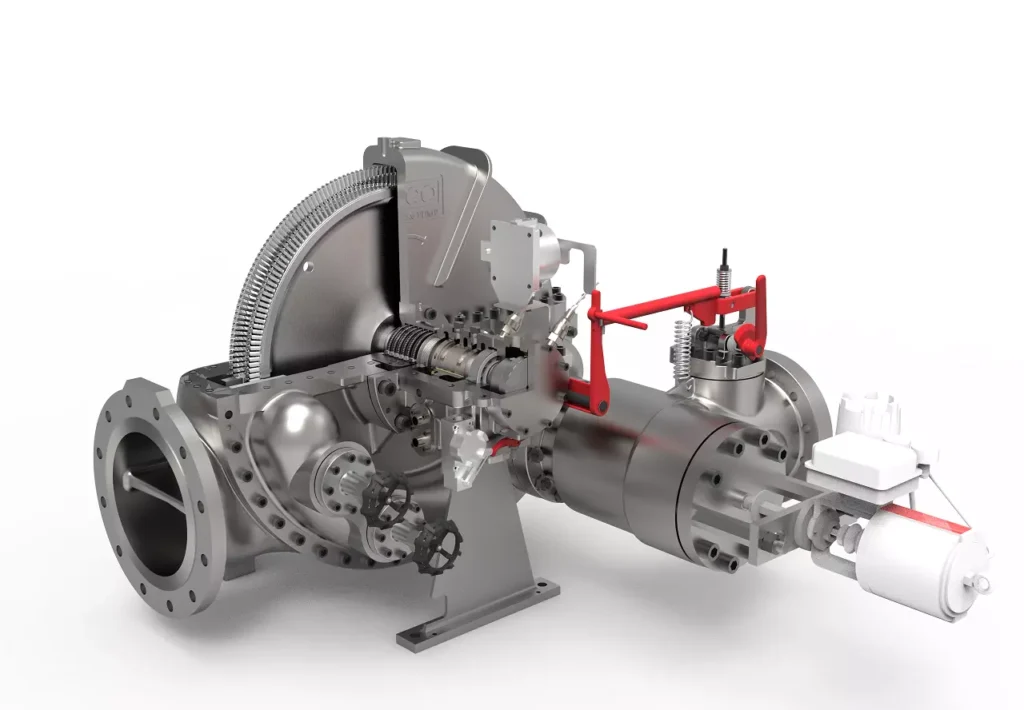

Micro ORC Turbine

A micro ORC turbine is a key component in a micro Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system. It is a small-scale turbine designed to convert thermal energy, typically in the form of low-grade heat, into mechanical power, which is then used to generate electricity. The turbine works within the ORC process, which is similar to the conventional Rankine Cycle used in large-scale power plants, but optimized for smaller, lower-temperature applications.

How a Micro ORC Turbine Works:

- Heat Input: The process begins with a heat source, which could be industrial waste heat, geothermal energy, biomass, or solar thermal energy. This heat is used to vaporize an organic working fluid with a low boiling point.

- Expansion in the Turbine: The organic fluid, now in a high-pressure vapor state, enters the micro ORC turbine. Inside the turbine, the high-pressure vapor expands, causing the turbine blades to spin. The spinning turbine converts the thermal energy from the organic fluid into mechanical energy.

- Mechanical Power to Electricity: The mechanical energy generated by the turbine is then used to drive a generator, which converts the rotational energy into electrical power. The electrical output can range from a few kilowatts (kW) to several hundred kW, depending on the size and design of the turbine and ORC system.

- Condensation and Recirculation: After passing through the turbine, the working fluid is cooled in a condenser, returning it to a liquid state. The condensed fluid is then pumped back into the evaporator to begin the cycle again.

Characteristics of Micro ORC Turbines:

- Size: Micro ORC turbines are much smaller than traditional steam turbines, typically designed for smaller-scale applications like industrial waste heat recovery, off-grid energy generation, and renewable energy applications.

- Working Fluid: The organic fluid used in a micro ORC turbine has a low boiling point, which allows the system to operate effectively at lower temperatures (80°C to 300°C). This makes the system suitable for recovering waste heat from various sources that would not be effective for traditional steam turbines.

- Compact Design: Micro ORC turbines are designed to be compact and efficient, capable of fitting into smaller installations where space is limited.

- Efficiency: While the efficiency of micro ORC turbines is generally lower than larger turbines in high-temperature systems, they are particularly useful for converting low-grade heat that would otherwise be wasted. The efficiency varies based on factors like the temperature of the heat source and the turbine’s design.

Advantages of Micro ORC Turbines:

- Utilization of Waste Heat: Micro ORC turbines are ideal for capturing and converting waste heat from industrial processes or other low-temperature sources into useful electrical power. This increases the overall energy efficiency of a system and helps reduce dependence on external electricity sources.

- Compact and Scalable: These turbines are small and modular, allowing them to be scaled up or down based on the specific power requirements of the application. They can be used in a wide range of settings, from small industrial plants to remote, off-grid locations.

- Environmentally Friendly: Since micro ORC turbines can operate with renewable and waste heat sources, they offer an environmentally friendly alternative to fossil fuel-based power generation, helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

- Cost-Effective: Although the upfront cost of a micro ORC system can be high, over time, the recovery of waste heat and reduced energy costs can lead to a positive return on investment. For industries with consistent waste heat, the payback period can be relatively short.

Applications:

- Industrial Waste Heat Recovery: Industries that produce heat as a byproduct, such as cement, steel, and chemical manufacturing, can benefit from micro ORC turbines. By recovering waste heat and converting it into electricity, these industries can reduce their energy costs and improve the overall efficiency of their operations.

- Geothermal Energy: Micro ORC turbines are also used in geothermal power generation, where they convert the heat from geothermal wells into electricity, particularly in areas where geothermal resources are not hot enough to be harnessed by conventional steam turbines.

- Biomass and Waste-to-Energy: In biomass power plants or waste-to-energy facilities, micro ORC turbines can convert heat from burning organic materials into electricity, supporting renewable energy generation and waste management.

- Off-Grid and Remote Power Generation: Micro ORC turbines are useful in remote or off-grid locations where other forms of electricity generation might not be feasible. They can be powered by local waste heat, biomass, or solar thermal energy, providing a sustainable and reliable power source.

Challenges:

- Initial Cost: The initial investment in a micro ORC turbine system can be high, although it may be offset by long-term savings in energy costs and operational efficiencies. Advances in technology and economies of scale may reduce these costs over time.

- Heat Source Dependency: The performance of the turbine is directly tied to the availability and consistency of the heat source. Systems relying on industrial waste heat, for example, may face fluctuations in heat availability based on production schedules, which can impact the turbine’s output.

- Maintenance: Although micro ORC turbines are relatively low-maintenance compared to larger turbines, they still require periodic maintenance, particularly to ensure the efficiency of the turbine blades, seals, and working fluid. Regular maintenance is essential to maximize their lifespan and performance.

Future Developments:

Ongoing advancements in turbine design and organic working fluids are expected to improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of micro ORC turbines. New turbine materials, for instance, could increase durability and performance, allowing these systems to operate at higher efficiencies. Additionally, the development of advanced control systems and smart monitoring technologies will enable better optimization of turbine performance, particularly in applications where the heat source is variable.

As industries and communities continue to focus on sustainability and energy efficiency, micro ORC turbines are likely to play a growing role in converting waste heat into valuable electricity. Their compact size, versatility, and ability to operate with low-temperature heat sources make them an ideal solution for small-scale, decentralized power generation systems, contributing to a cleaner, more sustainable energy future.

Micro ORC turbines continue to evolve as an essential technology for energy recovery and small-scale power generation. They provide an efficient way to harness energy from low-temperature heat sources that would otherwise be wasted. As the world moves toward greater energy efficiency and sustainability, the role of micro ORC turbines in reducing energy consumption and lowering carbon emissions becomes increasingly important.

These turbines not only offer a method for waste heat recovery but also help in reducing the reliance on traditional energy sources, especially fossil fuels. Their integration into various sectors, from manufacturing plants to remote locations, brings the possibility of decentralized energy generation, which improves energy resilience and security. Additionally, since micro ORC turbines can operate off-grid, they present a promising solution for areas lacking reliable access to centralized power infrastructure, particularly in developing countries or isolated regions.