Mechanical Efficiency of Steam Turbine: A steam turbine generator is a device that converts thermal energy from steam into mechanical energy using a steam turbine and then converts that mechanical energy into electrical energy using a generator. It is a key component in power generation systems, commonly found in power plants, industrial facilities, and cogeneration systems.

Main Components of a Steam Turbine Generator

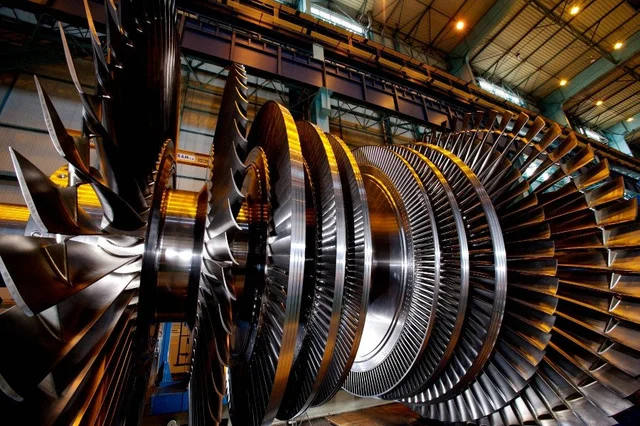

- Steam Turbine – Converts thermal energy of steam into rotational mechanical energy.

- Impulse Turbine: Uses high-velocity steam jets to rotate the blades.

- Reaction Turbine: Uses steam expansion through fixed and moving blades to generate motion.

- Generator – Converts mechanical energy from the turbine into electrical energy via electromagnetic induction.

- Condenser (for condensing turbines) – Condenses exhaust steam to improve efficiency by creating a vacuum.

- Boiler (External Component) – Generates high-pressure steam by heating water.

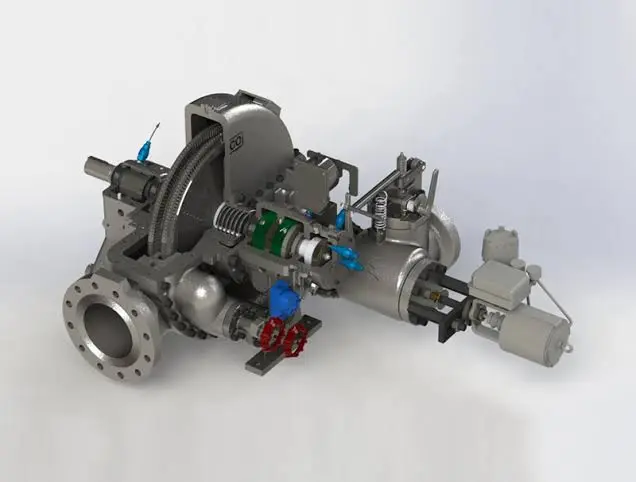

- Steam Control Valves – Regulate steam flow into the turbine.

- Lubrication System – Ensures smooth turbine operation by reducing friction.

- Cooling System – Maintains the temperature of components to prevent overheating.

Types of Steam Turbine Generators

- Condensing Steam Turbine Generator

- Utilized in power plants.

- Steam exhausts into a condenser, creating a vacuum for maximum energy extraction.

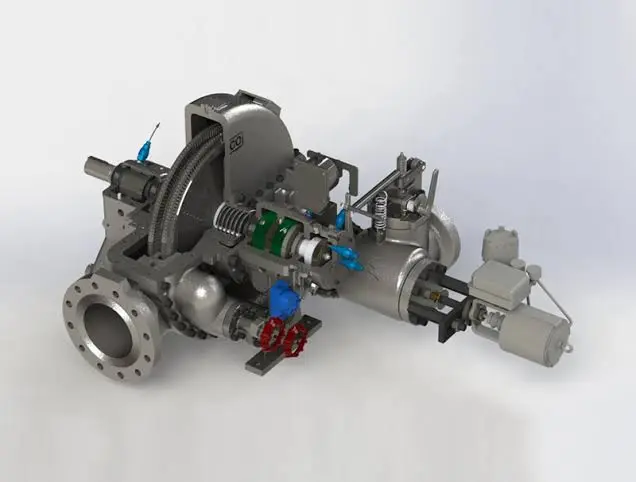

- Back-Pressure Steam Turbine Generator

- Used in industrial and cogeneration applications.

- Exhaust steam is used for heating or industrial processes.

- Extraction Steam Turbine Generator

- Allows steam extraction at different stages for industrial or heating use.

- Can be designed for partial condensing or back-pressure operation.

Working Principle of a Steam Turbine Generator

- Steam Production: High-pressure steam is generated in a boiler.

- Steam Expansion: Steam enters the turbine, expanding through nozzles and causing blades to rotate.

- Mechanical Energy Transfer: The rotating turbine shaft drives the generator.

- Electrical Power Generation: The generator converts mechanical energy into electricity through electromagnetic induction.

- Steam Exhaust: Steam exits either to a condenser (for a condensing turbine) or for industrial use (for a back-pressure turbine).

Applications of Steam Turbine Generators

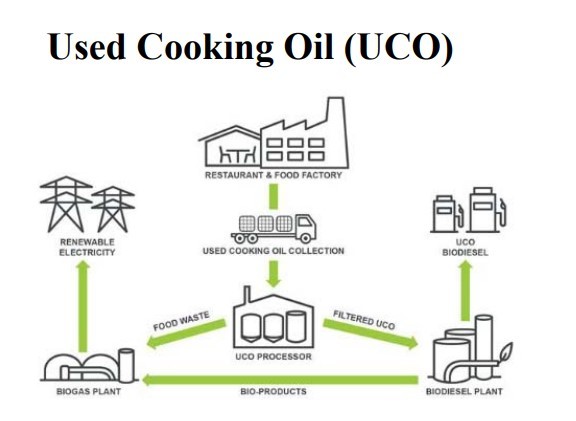

- Power Plants: Coal, nuclear, biomass, and combined cycle plants.

- Industrial Cogeneration: Paper mills, chemical plants, refineries.

- Geothermal Power Plants: Uses steam from underground reservoirs.

- Marine Propulsion: Some ships use steam turbines for power generation.

A steam turbine generator is a machine that converts steam energy into electrical power. It consists of two main parts:

- Steam Turbine – This is where high-pressure steam enters and pushes the blades, causing the rotor to spin. The turbine works by either impulse or reaction principles.

- Generator – The spinning turbine shaft connects to a generator, which produces electricity through electromagnetic induction.

How It Works

- Water is heated in a boiler to produce steam.

- High-pressure steam enters the turbine and expands, causing the blades to rotate.

- The rotating shaft drives a generator, converting mechanical energy into electrical energy.

- The steam then exits the turbine—either to a condenser (in condensing turbines) or for industrial use (in back-pressure turbines).

Types of Steam Turbine Generators

- Condensing Turbines – Used in power plants; exhaust steam is condensed to improve efficiency.

- Back-Pressure Turbines – Used in industries where the exhaust steam is needed for heating or processing.

- Extraction Turbines – Steam is extracted at intermediate stages for industrial use while still generating power.

Applications

- Power generation in thermal power plants (coal, nuclear, biomass, geothermal).

- Industrial cogeneration (paper mills, chemical plants, refineries).

- Marine propulsion (some ships use steam turbines).

Efficiency and Performance of Steam Turbine Generators

The efficiency of a steam turbine generator depends on several factors, including steam conditions, turbine design, and energy losses.

Factors Affecting Efficiency

- Steam Pressure and Temperature – Higher steam pressure and temperature increase efficiency by extracting more energy.

- Turbine Blade Design – Optimized blade profiles improve energy conversion.

- Multiple Stages – Using high, intermediate, and low-pressure stages enhances efficiency.

- Reheating and Regeneration – Preheating feedwater using extracted steam improves cycle efficiency.

- Condenser Vacuum – A lower condenser pressure (deep vacuum) increases energy extraction.

Typical Efficiency Levels

- Simple steam turbines: 30–40% thermal efficiency.

- Advanced steam cycles (with reheating and regeneration): 40–45%.

- Combined cycle power plants (steam + gas turbines): 55–60%.

Maintenance and Reliability

Regular maintenance ensures longevity and performance. Key aspects include:

- Lubrication System Checks – Prevents friction damage to bearings and rotating parts.

- Blade Inspection – Detects erosion, corrosion, or cracking.

- Steam Quality Control – Avoids deposits and corrosion inside the turbine.

- Generator Cooling System – Prevents overheating of electrical components.

- Vibration Monitoring – Identifies imbalances and potential failures early.

Advantages of Steam Turbine Generators

✔ High efficiency for large-scale power generation.

✔ Long operational lifespan with proper maintenance.

✔ Suitable for a wide range of fuels (coal, biomass, nuclear, geothermal).

✔ Can be integrated with industrial processes for cogeneration.

Types of Steam Turbines in Detail

Steam turbines can be classified based on their operating principles and applications.

1. Based on Energy Conversion Principle

- Impulse Turbine – Steam expands through nozzles, converting pressure energy into kinetic energy. The high-speed steam jets strike the blades, causing rotation. Example: De Laval Turbine.

- Reaction Turbine – Steam expands gradually through both fixed and moving blades, generating reaction forces that drive rotation. Example: Parsons Turbine.

2. Based on Exhaust Conditions

- Condensing Turbine – Common in power plants; steam exhausts into a condenser, creating a vacuum that maximizes energy extraction.

- Back-Pressure Turbine – Used in cogeneration systems; exhaust steam is utilized in industrial processes, improving overall efficiency.

- Extraction Turbine – Allows steam to be extracted at intermediate stages for heating or industrial use while still generating power.

- Bleed Turbine – Similar to an extraction turbine but with uncontrolled steam extraction for feedwater heating.

3. Based on Flow Direction

- Axial Flow Turbine – Steam moves along the shaft axis; widely used in power generation.

- Radial Flow Turbine – Steam flows radially inward or outward; used in small-scale applications.

Steam Turbine Generator Operation Modes

- Base Load Operation – The turbine runs continuously at high efficiency, supplying steady power. Used in coal, nuclear, and large-scale thermal plants.

- Peak Load Operation – The turbine is operated only when demand is high. More common in smaller or supplementary power plants.

- Cogeneration Mode – Generates electricity while supplying steam for industrial processes, maximizing efficiency.

Common Challenges in Steam Turbine Operation

- Blade Erosion and Corrosion – Caused by moisture and impurities in steam.

- Thermal Stress and Fatigue – Due to frequent start-stop cycles or temperature fluctuations.

- Steam Quality Issues – Poor steam quality leads to deposits, scaling, and reduced efficiency.

- Generator Overheating – Requires effective cooling mechanisms like hydrogen or water cooling.

- Vibration and Imbalance – Can cause mechanical failures if not monitored.

Future Trends in Steam Turbine Technology

- Supercritical and Ultra-Supercritical Steam Cycles – Operating at higher pressures and temperatures to improve efficiency.

- Integrated Renewable Hybrid Systems – Combining steam turbines with solar or biomass energy for sustainable power generation.

- Advanced Materials and Coatings – Using high-temperature-resistant alloys to enhance turbine lifespan.

- Digital Monitoring and AI-Based Predictive Maintenance – Improving reliability through real-time performance tracking and automated diagnostics.

Steam Turbine Manufacturing Process

The manufacturing of steam turbines is a complex, high-precision process that involves several stages, from material selection to final assembly and testing. Below is a detailed breakdown of the process.

Design and Engineering

Before manufacturing begins, engineers design the steam turbine based on the intended application, steam conditions, and efficiency requirements.

- Thermodynamic Analysis – Determines steam flow, pressure, and temperature requirements.

- Structural Design – Ensures the turbine casing, rotor, and blades can withstand operational stresses.

- Material Selection – High-strength alloys are used to resist high temperatures and pressures.

- Computer-Aided Design (CAD) & Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) – Optimize turbine blade profiles for maximum efficiency.

Material Selection and Procurement

Steam turbines operate under extreme conditions, so high-quality materials are essential.

- Rotor & Casing: Forged from high-strength steel alloys (e.g., chromium-molybdenum-vanadium steel).

- Blades: Made from stainless steel or nickel-based superalloys to resist corrosion and high temperatures.

- Bearings & Seals: High-precision alloys or composite materials ensure smooth operation.

Component Manufacturing

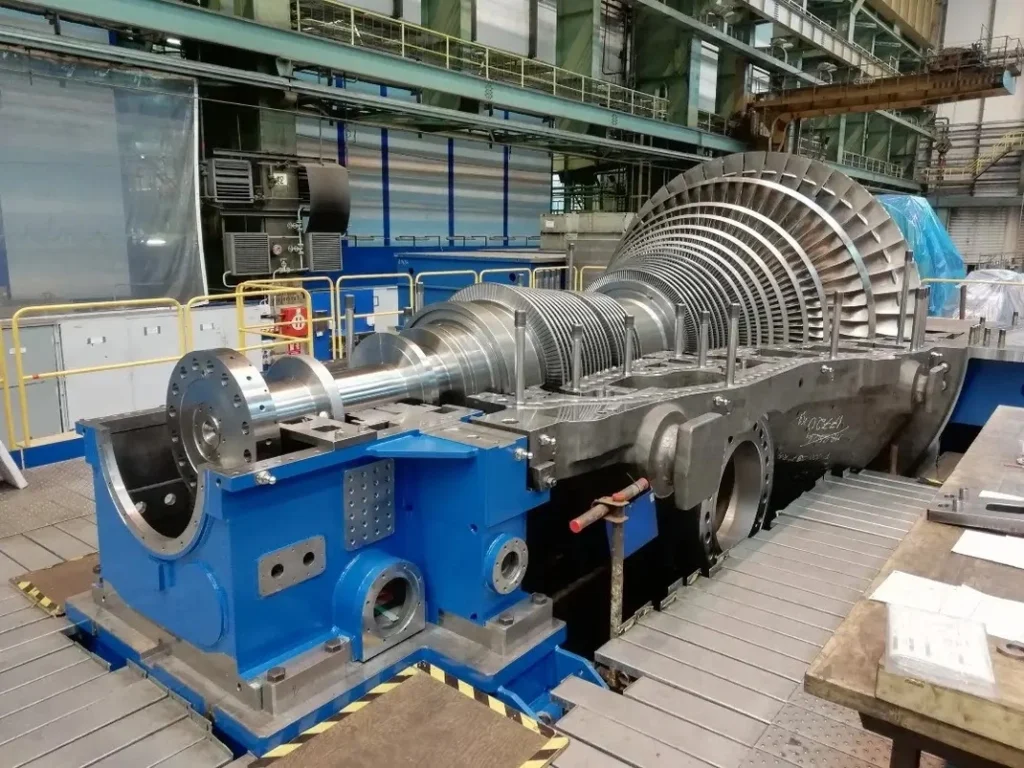

a) Rotor Manufacturing

- Forged steel billets are heated and forged into the rotor shape.

- Precision machining on CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines ensures accurate dimensions.

- Heat treatment (quenching, tempering) improves strength and toughness.

- Balancing and inspection are performed to minimize vibration.

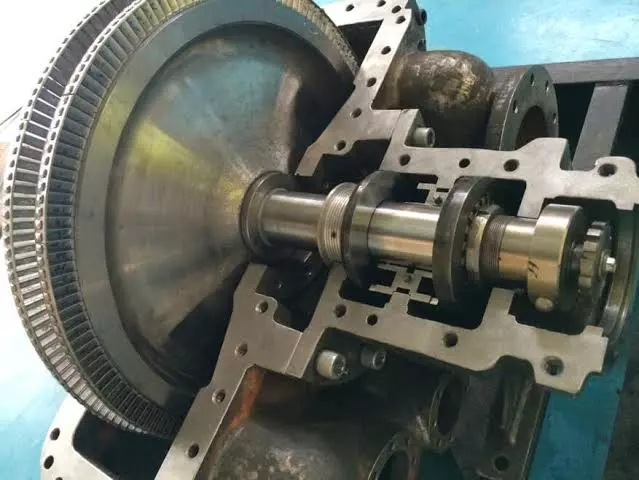

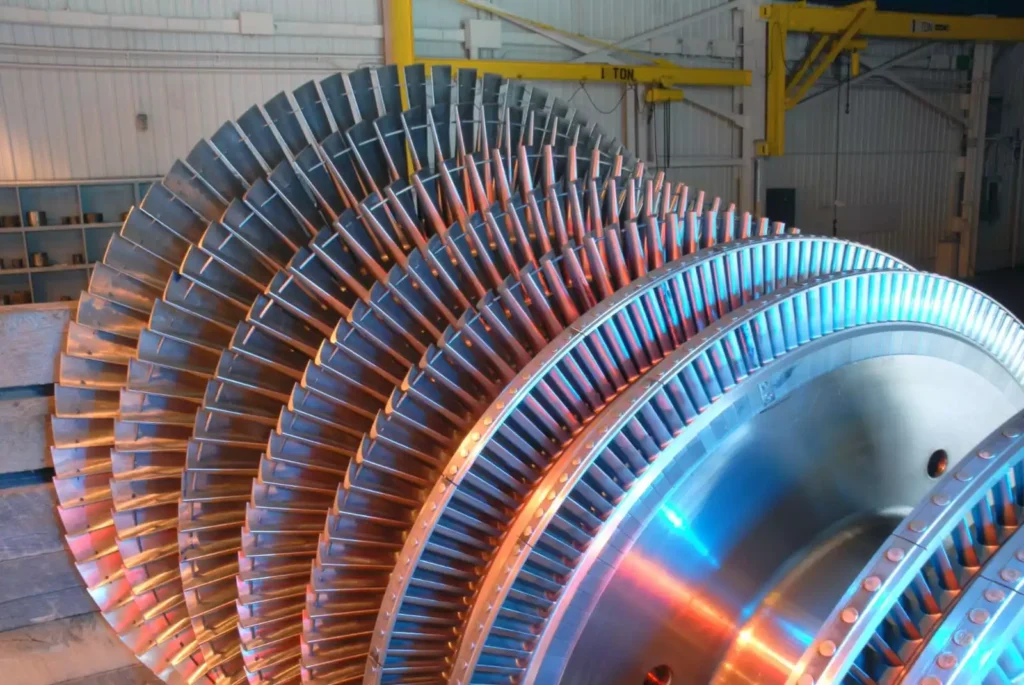

b) Blade Manufacturing

- Steam turbine blades are forged or cast depending on size and material.

- CNC machining creates the aerodynamic profile.

- Surface coatings (like thermal barrier coatings) enhance durability.

- Quality checks ensure proper fit and performance.

c) Casing and Other Structural Components

- The turbine casing is cast or fabricated from heavy-duty steel.

- Machining and drilling ensure accurate alignment with the rotor and steam inlets.

- Welding and assembly of internal components are performed with precision.

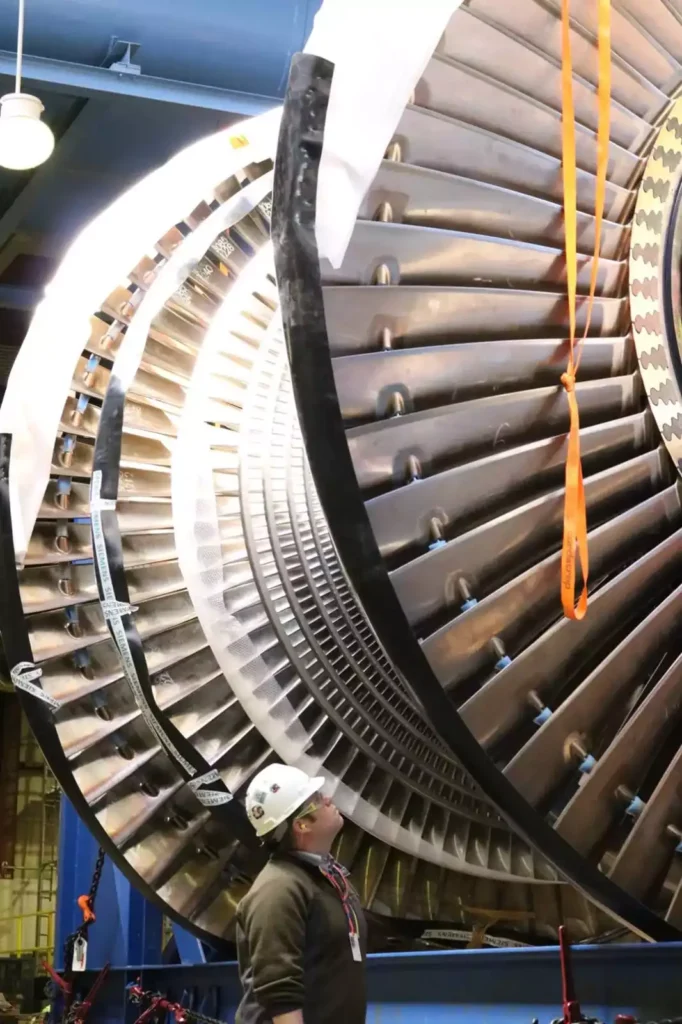

Assembly and Integration

- The rotor is mounted inside the casing with precise tolerances.

- Blades are attached using rivets or fir-tree root designs.

- Bearings, seals, and lubrication systems are installed.

- The generator is coupled to the turbine shaft for power conversion.

Quality Control and Testing

a) Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

- Ultrasonic Testing (UT): Detects internal flaws in turbine components.

- Magnetic Particle Testing (MPT): Identifies surface cracks in rotor and blades.

- X-ray and Radiographic Testing: Ensures weld integrity.

b) Mechanical and Performance Testing

- Rotor Balancing: Ensures smooth operation and minimizes vibration.

- Pressure & Leak Tests: Check for steam leakage under high pressure.

- Full Load Testing: Simulates real-world operating conditions to verify performance.

Final Assembly and Shipping

- After successful testing, the turbine is disassembled into transportable sections.

- It is packaged and shipped to the power plant or industrial facility for installation.

- On-site installation includes foundation mounting, alignment, and commissioning.

The manufacturing of steam turbines begins with the design and engineering phase, where engineers determine the turbine’s specifications based on its intended application. This includes analyzing steam pressure, temperature, and flow rates while optimizing the blade profiles for maximum efficiency using computer simulations. High-strength materials such as chromium-molybdenum-vanadium steel for the rotor and nickel-based superalloys for the blades are selected to withstand extreme conditions.

The rotor is forged from a steel billet, then precision-machined and heat-treated to improve strength. Blades are either cast or forged, shaped using CNC machines, and coated to enhance durability. The turbine casing is cast or fabricated from heavy-duty steel, then machined for precise alignment. Bearings, seals, and other critical components are also manufactured with high precision.

During assembly, the rotor is installed in the casing, and the blades are attached using secure mounting techniques. The generator is coupled to the turbine shaft, and all components are aligned carefully. Quality control involves rigorous non-destructive testing methods such as ultrasonic and X-ray inspections to detect flaws. Performance tests, including rotor balancing and full-load testing, ensure the turbine operates efficiently and reliably.

After final assembly, the turbine is disassembled into transportable sections, shipped to the installation site, and reassembled for commissioning. Leading manufacturers of steam turbines include Siemens, General Electric, Mitsubishi Power, Toshiba, Doosan Škoda, BHEL, and Harbin Electric. Each company specializes in different turbine types, including those used in power plants, cogeneration systems, and industrial applications.

Once the steam turbine is manufactured and assembled, it undergoes extensive quality control and performance testing before being deployed for industrial or power generation use. Testing begins with non-destructive evaluation techniques such as ultrasonic testing to detect internal defects, magnetic particle testing to identify surface cracks, and radiographic X-ray inspections to ensure weld integrity. These tests help verify that the turbine components can withstand high pressures and temperatures without failure.

Rotor balancing is a critical step to ensure smooth operation and minimize vibration. Any imbalance can cause excessive wear on bearings and reduce the lifespan of the turbine. Pressure and leak tests are also conducted to check for steam leakage and ensure that all seals and joints perform as expected under real operating conditions. Full-load performance testing is carried out by running the turbine at different speeds and loads to evaluate efficiency, power output, and thermal stability.

After passing all quality checks, the turbine is prepared for shipment. Since turbines are often too large to transport in one piece, they are disassembled into sections, securely packaged, and transported to the power plant or industrial facility. Upon arrival, installation begins with precise alignment on a reinforced foundation. Engineers reassemble the turbine, connect it to the generator and steam supply system, and conduct final inspections before commissioning.

During commissioning, engineers gradually increase the turbine’s load while monitoring parameters like temperature, pressure, rotational speed, and vibration levels. Control systems are tested, safety mechanisms are verified, and operational fine-tuning is performed to achieve optimal performance. Once everything is confirmed to be working as expected, the turbine is put into full operation, providing reliable power generation or steam for industrial processes.

Once the steam turbine is fully operational, continuous monitoring and maintenance are essential to ensure long-term reliability and efficiency. Operators use advanced monitoring systems to track critical parameters such as steam temperature, pressure, rotational speed, vibration, and lubrication conditions. Any irregularities in these readings can indicate potential issues, allowing for preventive maintenance before serious damage occurs.

Routine maintenance includes inspecting turbine blades for erosion or corrosion, checking seals and bearings for wear, and ensuring proper lubrication to reduce friction. Over time, deposits can accumulate on turbine blades due to impurities in steam, reducing efficiency. Periodic cleaning and surface treatment help restore optimal performance. The generator also requires regular maintenance, including cooling system checks and insulation testing to prevent electrical failures.

Predictive maintenance technologies, such as vibration analysis and thermal imaging, help identify early signs of mechanical stress, misalignment, or overheating. Many modern turbines are equipped with AI-driven diagnostic systems that analyze real-time data and provide predictive failure alerts, minimizing downtime and costly repairs.

Despite rigorous maintenance, some turbine components have a finite lifespan and require periodic overhauls. Major overhauls involve disassembling the turbine, replacing worn-out parts, and rebalancing the rotor. In large power plants, these overhauls are scheduled during planned outages to avoid disruption to power supply.

As steam turbine technology evolves, manufacturers are developing new materials, coatings, and digital monitoring solutions to extend turbine lifespans and improve efficiency. Ultra-supercritical steam turbines, for example, operate at higher temperatures and pressures, increasing power output while reducing fuel consumption. Advances in automation and remote monitoring also enable operators to optimize turbine performance in real time, further enhancing reliability and operational flexibility.

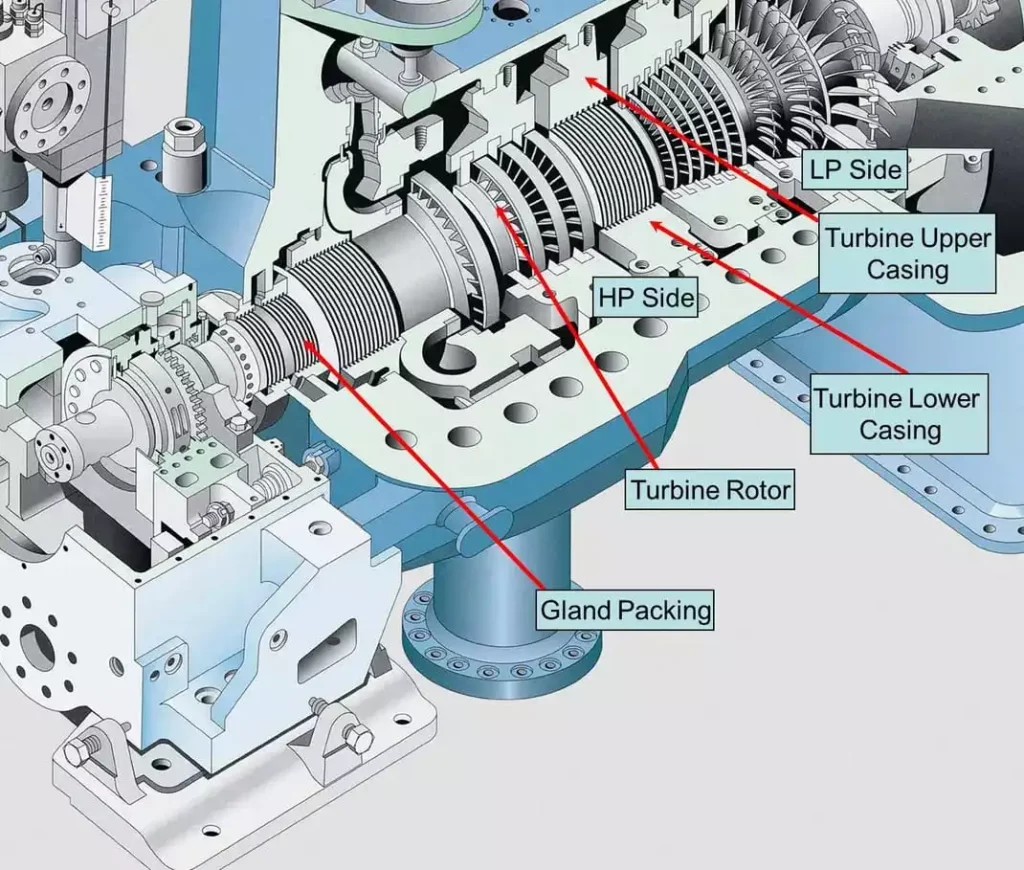

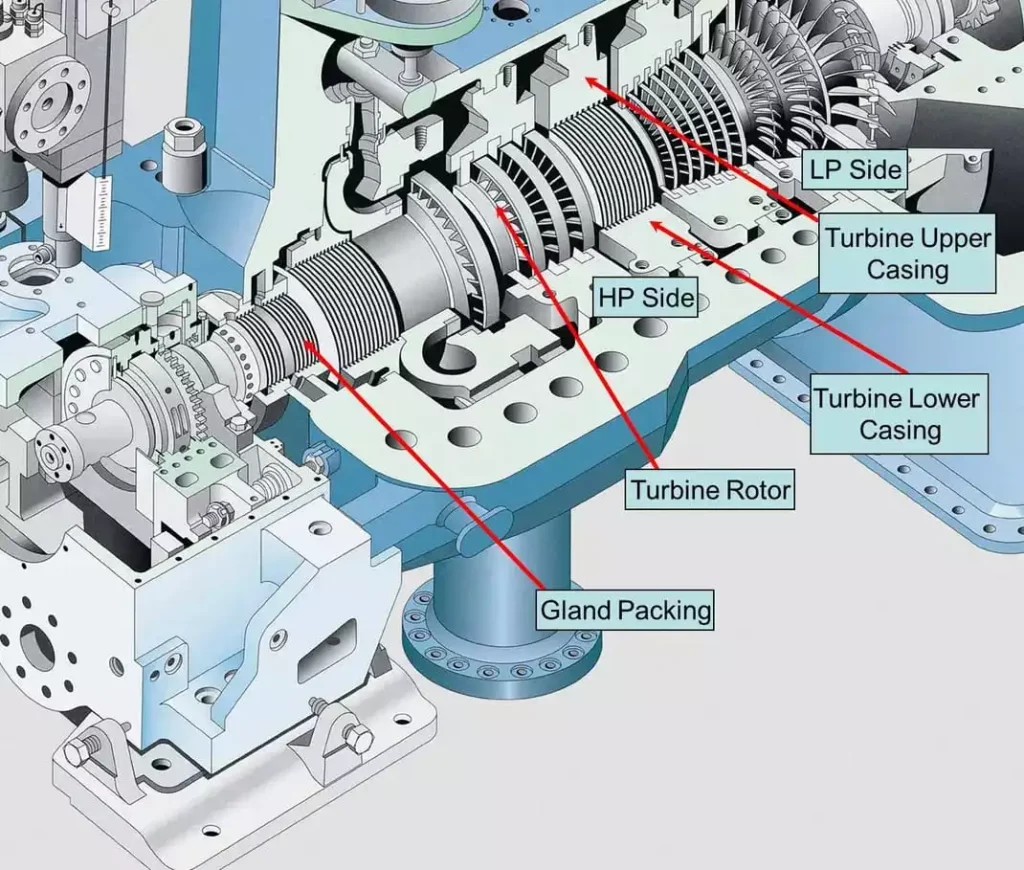

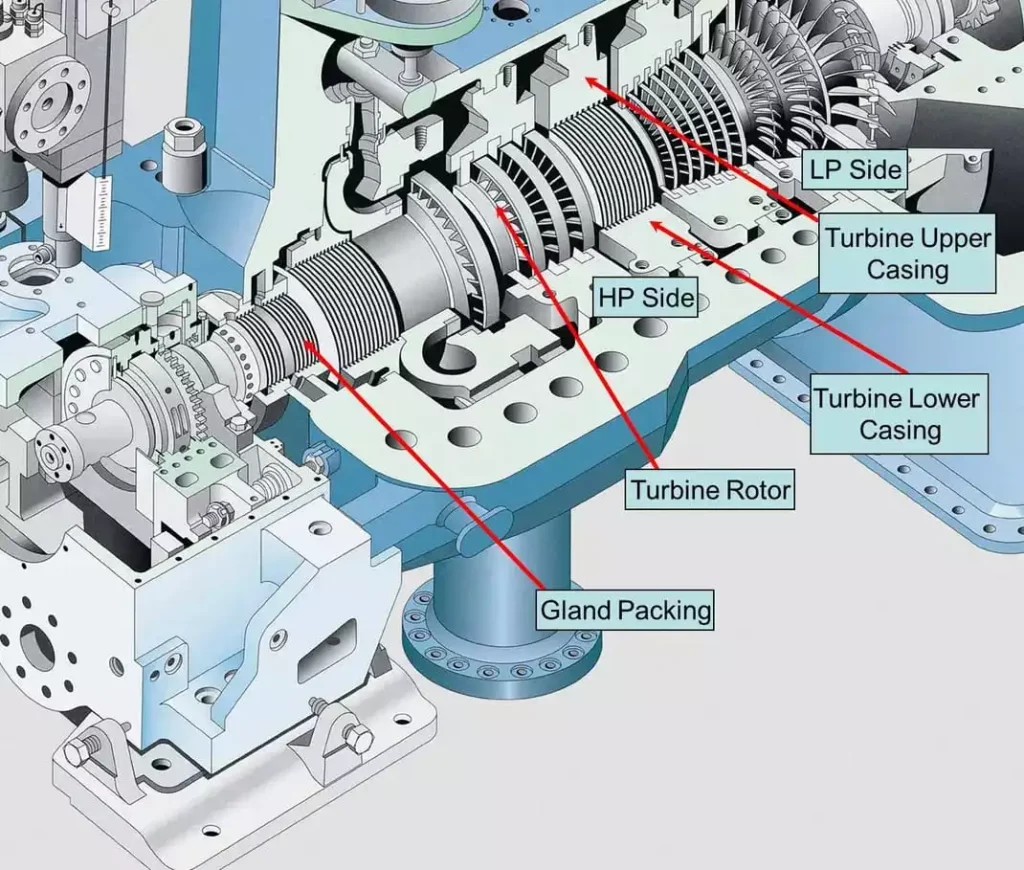

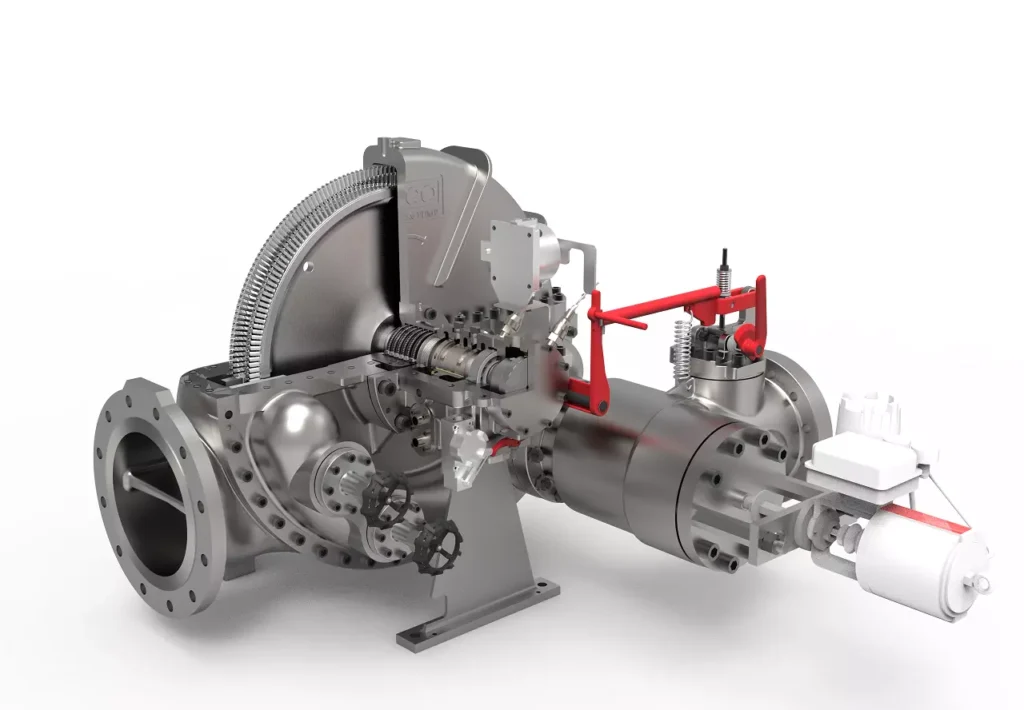

Construction of steam turbine

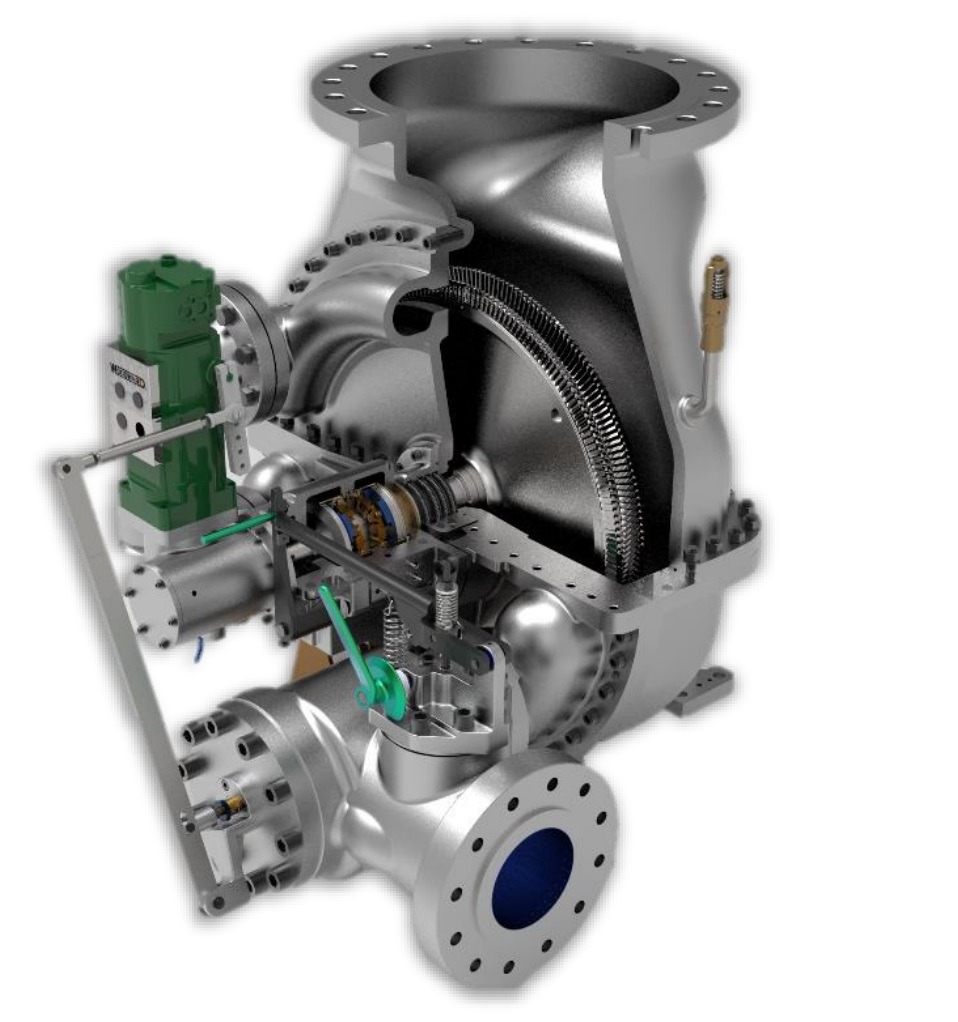

The construction of a steam turbine involves multiple high-precision components designed to efficiently convert thermal energy from steam into mechanical power. Each component is engineered to withstand extreme temperatures, pressures, and rotational forces while maintaining efficiency and durability.

Main Components of a Steam Turbine

- Rotor (Shaft) – The central rotating component that carries the blades and transmits mechanical power to the generator. It is typically made of high-strength forged steel to handle high-speed rotation and stress.

- Blades – Steam turbine blades are mounted on the rotor and are responsible for extracting energy from steam. They are made of heat-resistant alloys and designed aerodynamically to maximize efficiency. Blades can be categorized as:

- Moving blades (rotor blades): Attached to the rotating shaft and convert steam energy into rotational motion.

- Fixed blades (stator blades or nozzles): Stationary blades that direct and accelerate steam onto the moving blades.

- Casing (Housing) – The outer structure that encloses the turbine and contains the steam. It is typically made of cast steel or welded steel plates and designed to withstand high pressures.

- Steam Inlet and Control Valves – These regulate the flow of high-pressure steam entering the turbine. The valves help control power output by adjusting the steam supply.

- Bearings and Lubrication System – Bearings support the rotor and reduce friction. The lubrication system ensures smooth operation by supplying oil to bearings, preventing overheating and wear.

- Seals and Glands – Prevent steam leakage at high-speed rotating parts. These seals help maintain efficiency by ensuring steam remains in the desired flow path.

- Condenser (for condensing turbines) – In a condensing steam turbine, the exhaust steam is directed to a condenser, where it is cooled and converted back into water to improve efficiency.

- Extraction or Exhaust System – In some turbines, part of the steam is extracted at intermediate stages for industrial heating or further processing, while the remaining steam continues expansion for power generation.

Construction Process

- Material Selection – High-strength steel alloys and corrosion-resistant materials are chosen for turbine components.

- Forging and Machining – The rotor and blades are forged and precisely machined using CNC technology.

- Casting and Fabrication – The turbine casing is cast or fabricated to withstand high pressures.

- Blade Assembly – Blades are mounted on the rotor using specialized fastening techniques such as fir-tree root fixing or welding.

- Final Assembly – The rotor, bearings, seals, and other components are assembled within the casing.

- Balancing and Testing – The assembled turbine undergoes rigorous testing to ensure smooth operation, vibration control, and steam tightness.

- Installation and Commissioning – The turbine is transported, installed on-site, connected to the generator and steam system, and tested before full operation.

The construction of a steam turbine involves assembling high-precision components designed to withstand extreme pressures, temperatures, and rotational forces while ensuring maximum efficiency and durability. The central component is the rotor, a high-strength forged steel shaft that carries the turbine blades and transmits mechanical power to the generator. The blades, made from heat-resistant alloys, are mounted on the rotor and play a crucial role in extracting energy from steam. These blades are designed aerodynamically to maximize efficiency, with moving blades attached to the rotor and stationary blades directing steam flow.

The turbine casing, made of cast or welded steel, encloses the rotor and blades while containing high-pressure steam. Steam enters through control valves that regulate its flow and adjust power output. Bearings support the rotor and minimize friction, while a lubrication system ensures smooth operation and prevents overheating. Specialized seals prevent steam leakage at rotating parts, maintaining efficiency by keeping steam within the designated flow path. In condensing turbines, a condenser cools and converts exhaust steam back into water to improve the cycle’s efficiency, whereas in extraction turbines, part of the steam is extracted for industrial heating or further processing.

The manufacturing process begins with selecting high-strength steel alloys and corrosion-resistant materials. The rotor and blades are forged and precisely machined using CNC technology, while the casing is cast or fabricated to withstand operational stresses. Blades are securely mounted onto the rotor using fir-tree root fixing or welding techniques. During final assembly, the rotor, blades, bearings, seals, and auxiliary systems are integrated within the casing, ensuring proper alignment. The turbine undergoes rigorous balancing and performance testing to eliminate vibrations, check for leaks, and verify operational efficiency. After passing quality control, it is transported to the installation site, mounted on a foundation, connected to the generator and steam supply, and commissioned for operation. The entire construction process ensures long-term reliability and efficiency in power generation and industrial applications.

Once the steam turbine is installed and commissioned, its operation relies on precise coordination between various components to ensure efficient energy conversion. Steam is introduced into the turbine at high pressure and temperature through the control valves, which regulate its flow based on power demand. As the steam passes through the stationary blades, it is directed onto the rotating blades, where it expands and loses pressure while transferring kinetic energy to the rotor. This rotational energy is transmitted to the generator, converting mechanical power into electricity. The process continues across multiple turbine stages, with each stage extracting additional energy from the steam.

The efficiency of a steam turbine depends on several factors, including the quality of steam, blade design, and operating conditions. Over time, factors like erosion, corrosion, and deposits from impurities in steam can affect performance, making regular maintenance essential. Bearings and lubrication systems are monitored continuously to prevent excessive wear and overheating, while vibration sensors detect potential misalignment or imbalance in the rotor. Advanced monitoring systems use real-time data to analyze operational efficiency and predict maintenance needs, reducing unexpected failures and improving reliability.

In condensing turbines, exhaust steam is directed to a condenser, where it is cooled and converted back into water before being pumped back to the boiler, creating a closed-loop system that enhances efficiency. In back-pressure or extraction turbines, a portion of the steam is diverted for industrial heating or other applications while the remaining steam continues expansion for power generation. This versatility makes steam turbines a critical component in power plants, cogeneration systems, and industrial processes.

As technology advances, modern steam turbines incorporate high-temperature-resistant materials, optimized blade geometries, and digital control systems to improve efficiency and extend operational life. Supercritical and ultra-supercritical turbines operate at even higher pressures and temperatures, reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Ongoing research in materials science and automation continues to enhance turbine performance, ensuring their role remains vital in energy generation and industrial applications.

As steam turbine technology continues to evolve, improvements in materials, design, and digital monitoring systems are enhancing efficiency, reliability, and sustainability. Advanced alloys and thermal coatings are being developed to withstand higher temperatures and pressures, allowing turbines to operate in ultra-supercritical conditions with increased efficiency and reduced fuel consumption. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations help optimize blade geometries to improve steam flow and energy extraction, minimizing losses and extending component lifespans.

Digitalization plays a key role in modern turbine operation, with smart sensors and AI-driven analytics enabling real-time monitoring of critical parameters such as temperature, pressure, vibration, and steam flow. Predictive maintenance systems analyze operational data to identify potential issues before they cause failures, reducing unplanned downtime and maintenance costs. Remote monitoring capabilities allow operators to make adjustments and optimize performance without direct intervention, increasing flexibility and responsiveness in power generation.

In addition to efficiency gains, environmental concerns drive advancements in steam turbine integration with renewable energy sources. Hybrid power plants combine steam turbines with solar thermal, biomass, or waste heat recovery systems to maximize energy utilization and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies are also being integrated into steam power plants to mitigate environmental impact.

Looking ahead, research in advanced manufacturing techniques, such as additive manufacturing (3D printing), could revolutionize steam turbine production by allowing for complex, high-efficiency blade designs with reduced material waste. As global energy demands continue to grow, steam turbines remain a crucial component in electricity generation, industrial processes, and combined heat and power (CHP) systems. Their adaptability, durability, and potential for further efficiency improvements ensure they will continue to play a vital role in the future of energy production.

Characteristics of steam turbine

Steam turbines have several key characteristics that define their performance, efficiency, and suitability for various applications. They are widely used in power generation, industrial processes, and cogeneration systems due to their ability to convert thermal energy from steam into mechanical power with high efficiency and reliability.

One of the primary characteristics of a steam turbine is its high thermal efficiency, especially in large-scale power plants where superheated or ultra-supercritical steam conditions are used. The efficiency of a steam turbine depends on factors such as steam pressure, temperature, expansion ratio, and blade design. Multi-stage turbines, which consist of multiple sets of rotating and stationary blades, extract energy from steam more effectively by allowing gradual expansion and pressure reduction.

Steam turbines operate with a continuous rotary motion, unlike reciprocating engines, which experience cyclic motion. This results in smoother operation, reduced mechanical stress, and lower vibration levels, contributing to longer operational life and lower maintenance requirements. Their high-speed rotation allows them to be directly coupled to electrical generators, enabling efficient power generation with minimal mechanical losses.

The power output of a steam turbine can be controlled by regulating the steam flow through inlet control valves, allowing flexible operation to match varying power demands. In condensing steam turbines, the exhaust steam is directed to a condenser, where it is cooled and converted back into water for reuse in a closed-loop system, maximizing efficiency. In back-pressure and extraction turbines, steam is partially or fully extracted at intermediate stages for industrial heating or other applications, demonstrating their versatility in combined heat and power (CHP) systems.

Steam turbines are designed to handle high pressures and temperatures, often exceeding 500°C and 100 bar in modern power plants. Advanced materials, coatings, and precision engineering ensure that components can withstand thermal stress, corrosion, and erosion over long periods. The reliability of steam turbines is one of their strongest characteristics, with many units operating continuously for years with minimal downtime. Predictive maintenance technologies, such as vibration analysis and real-time monitoring, further enhance reliability by detecting early signs of wear or misalignment.

Another important characteristic is scalability. Steam turbines can be designed for small industrial applications or large-scale power generation, with capacities ranging from a few megawatts to over 1,000 megawatts in the case of nuclear and supercritical coal power plants. Their ability to integrate with different heat sources, including fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and renewable sources like biomass and solar thermal, makes them highly adaptable in diverse energy systems.

Overall, steam turbines are characterized by high efficiency, smooth continuous operation, flexible power control, durability, and the ability to operate under extreme conditions. Their advanced design, combined with modern digital monitoring and predictive maintenance systems, ensures their continued role as a reliable and efficient solution for large-scale energy conversion and industrial applications.

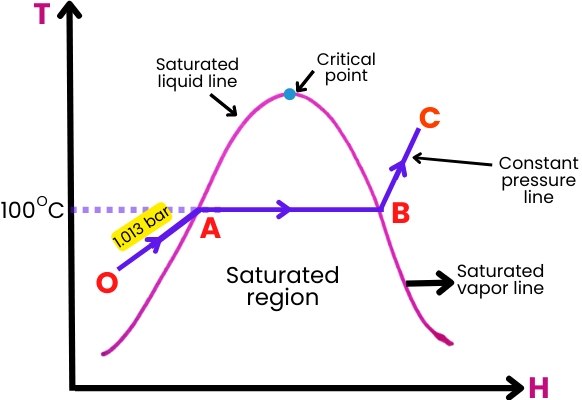

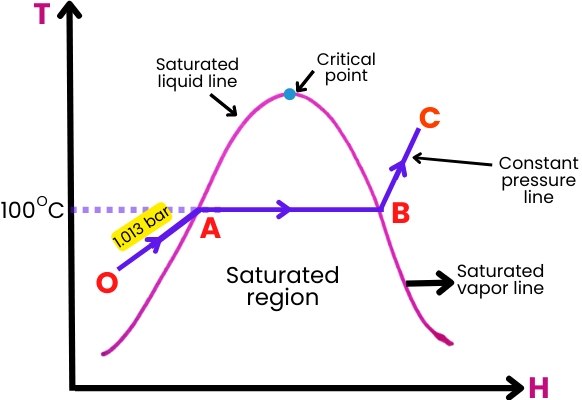

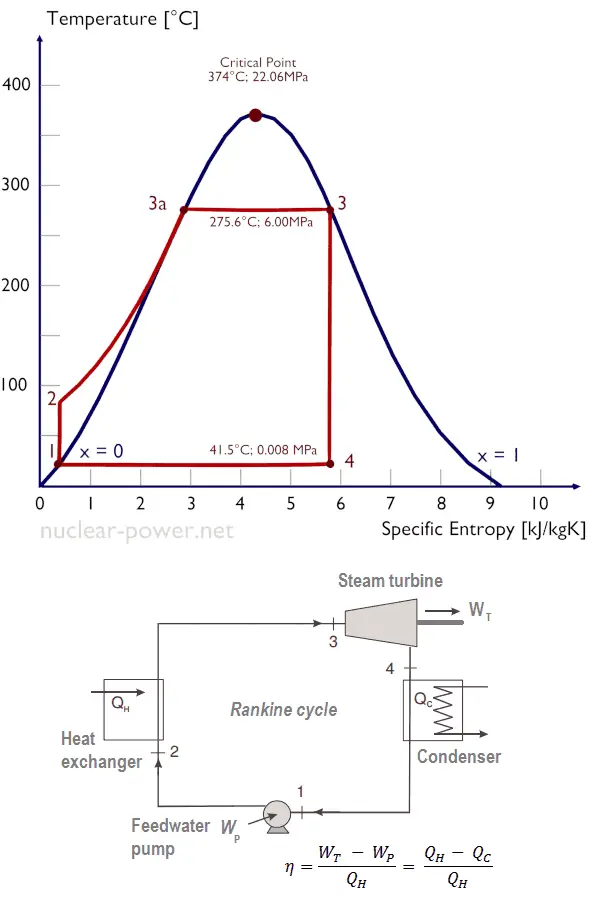

Steam turbines are known for their ability to operate at high efficiency under a wide range of conditions, making them a preferred choice for power generation and industrial applications. Their ability to extract maximum energy from steam depends on the thermodynamic cycle they operate within, typically the Rankine cycle, where high-pressure steam expands through multiple stages to convert thermal energy into mechanical work. This expansion process is optimized using multi-stage blade arrangements, where steam progressively loses pressure while transferring its kinetic energy to the rotor.

The rotational speed of a steam turbine is another defining characteristic. High-speed operation, often in the range of 3,000 to 3,600 RPM for power generation applications, allows them to be directly coupled with electrical generators, ensuring efficient energy conversion. Some turbines, particularly in specialized applications, can operate at even higher speeds, requiring reduction gears to match generator frequency. The smooth and continuous rotary motion minimizes mechanical wear and contributes to the long service life of steam turbines, often exceeding 30 years with proper maintenance.

The adaptability of steam turbines to various operating conditions is another key characteristic. They can function in condensing or non-condensing (back-pressure) configurations, depending on whether the exhaust steam is fully utilized or condensed back into water for reuse. Condensing turbines maximize efficiency by extracting the maximum possible energy from steam before it exits at low pressure, while back-pressure turbines are used where steam is needed for industrial heating or process applications. Extraction turbines further enhance flexibility by allowing steam withdrawal at intermediate stages for combined heat and power applications.

Modern steam turbines incorporate advanced materials and coatings to withstand extreme temperatures and pressures. Nickel-based superalloys, stainless steel, and thermal barrier coatings protect turbine blades from corrosion, erosion, and thermal fatigue, ensuring long-term reliability. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and finite element analysis (FEA) are used in blade design to optimize steam flow, minimize losses, and enhance performance. Digital monitoring systems equipped with smart sensors provide real-time diagnostics, predictive maintenance insights, and remote operational control, further improving efficiency and reliability.

Steam turbines continue to evolve with advancements in ultra-supercritical and high-efficiency designs, reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Their integration with renewable energy sources, such as biomass and solar thermal power, further expands their role in sustainable energy systems. As a result, they remain a cornerstone of global power generation, providing stable and efficient electricity in both traditional and modern energy infrastructure.

The ability of steam turbines to operate efficiently under varying conditions makes them highly versatile for different energy applications. Their efficiency is influenced by factors such as steam pressure, temperature, and the number of expansion stages. In modern power plants, ultra-supercritical steam turbines operate at pressures above 250 bar and temperatures exceeding 600°C, significantly increasing thermal efficiency and reducing fuel consumption. The integration of reheaters, which reheat steam after partial expansion, further improves efficiency by reducing moisture content and increasing energy extraction in later stages of the turbine.

Another key characteristic is the turbine’s durability and long operational life. Properly maintained steam turbines can operate continuously for years with minimal downtime. The robust design, use of high-quality materials, and advanced sealing technologies prevent steam leakage and ensure consistent performance. Bearings, lubrication systems, and rotor balancing play a crucial role in minimizing wear and vibration, extending the service life of the turbine. Routine inspections using non-destructive testing methods such as ultrasonic and thermal imaging help detect early signs of material fatigue, enabling proactive maintenance and preventing costly failures.

Steam turbines also offer flexible load-following capabilities, allowing them to adjust power output based on demand. While they are most efficient when operating at full load, modern control systems enable part-load operation with optimized steam flow regulation. In combined cycle power plants, steam turbines work alongside gas turbines, utilizing waste heat from the gas turbine to generate additional power through a heat recovery steam generator (HRSG), improving overall plant efficiency.

In industrial applications, steam turbines are widely used for mechanical drive purposes, powering compressors, pumps, and other equipment in oil refineries, chemical plants, and district heating systems. Their ability to utilize various steam sources, including waste heat from industrial processes, enhances energy efficiency and cost savings. Extraction and back-pressure turbines further increase operational flexibility by providing steam at different pressures for process heating, desalination, and other industrial uses.

As technology advances, digital monitoring and automation play an increasingly important role in steam turbine operations. Smart sensors collect real-time data on temperature, pressure, vibration, and efficiency, feeding into AI-driven predictive maintenance systems. These technologies help optimize performance, reduce maintenance costs, and extend turbine life by detecting issues before they lead to major failures. Remote monitoring and control allow operators to adjust turbine settings from centralized locations, improving operational efficiency and responsiveness.

Looking ahead, research into new materials, including ceramic-based coatings and additive manufacturing (3D printing) for turbine components, is expected to further enhance performance and efficiency. The continued development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies in steam power plants aims to reduce environmental impact, making steam turbines a crucial part of the transition to cleaner energy systems. Their proven reliability, adaptability, and efficiency ensure they will continue to play a key role in global energy production for decades to come.

Steam turbines remain a dominant technology in large-scale power generation due to their ability to provide stable and efficient energy conversion. Their adaptability to different fuel sources, including coal, natural gas, nuclear, biomass, and even concentrated solar power, makes them an integral part of the global energy mix. In nuclear power plants, steam turbines operate using high-temperature steam generated from nuclear reactors, where their long service life and high reliability are essential for continuous electricity production. Similarly, in fossil-fuel power plants, advanced steam cycles with supercritical and ultra-supercritical parameters continue to improve efficiency while reducing emissions.

One of the most significant developments in steam turbine technology is the integration of hybrid and renewable energy systems. In solar thermal power plants, steam turbines are used to convert heat energy collected from mirrors and heliostats into electricity. Biomass-fired steam turbines provide a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, utilizing organic waste materials for steam generation. Industrial cogeneration systems, which produce both electricity and usable heat, have also become increasingly popular due to their ability to achieve overall efficiencies of 80% or more by utilizing steam for both power generation and industrial processes.

Advancements in turbine design focus on improving aerodynamics, reducing energy losses, and increasing operational flexibility. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling is widely used to refine blade profiles, optimize steam flow, and minimize turbulence. The introduction of variable-pressure turbines allows for improved efficiency at part-load conditions, making them better suited for fluctuating power demands. Additionally, low-pressure last-stage blade designs are continuously evolving to reduce losses and increase the energy extracted from exhaust steam.

Automation and digitalization have transformed steam turbine operation and maintenance. Advanced control systems, utilizing machine learning algorithms and AI-driven analytics, optimize performance by adjusting steam flow, pressure, and temperature in real time. Digital twins—virtual models of turbines—are now used to simulate operating conditions, predict wear patterns, and suggest maintenance strategies before actual issues arise. This predictive approach minimizes unplanned downtime, extends equipment life, and reduces operational costs.

Looking forward, the role of steam turbines will continue to evolve as global energy priorities shift toward sustainability and efficiency. The development of advanced materials, such as ceramic matrix composites and corrosion-resistant alloys, will further enhance turbine durability and efficiency. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies are expected to become more integrated with steam power plants, reducing their carbon footprint. As energy systems modernize, steam turbines will remain a key player, whether in traditional power plants, hybrid renewable systems, or future energy innovations that demand reliable, high-efficiency power generation.

Development of steam turbine

The development of steam turbines has been a gradual process spanning several centuries, driven by advancements in engineering, materials science, and thermodynamics. From early experimental designs to the high-efficiency turbines used in modern power plants, steam turbine technology has continuously evolved to meet increasing demands for power generation, industrial applications, and efficiency improvements.

The concept of using steam to produce mechanical work dates back to the first century AD, with Hero of Alexandria’s primitive steam-powered device, the aeolipile. However, practical steam power did not emerge until the 17th and 18th centuries. The development of early steam engines by Thomas Savery and Thomas Newcomen provided the foundation for steam power, though these devices operated with low efficiency and were primarily used for pumping water. James Watt’s improvements to the steam engine in the late 18th century introduced the separate condenser, significantly increasing efficiency and making steam power more viable for industrial use.

The transition from reciprocating steam engines to rotary steam turbines was a major breakthrough in the late 19th century. In 1884, Charles Parsons invented the first practical steam turbine, using a multi-stage reaction principle to achieve continuous rotary motion with much greater efficiency than previous steam engines. Almost simultaneously, Gustaf de Laval developed an impulse turbine, which used high-velocity steam jets directed onto turbine blades. These innovations revolutionized power generation by enabling high-speed, high-efficiency energy conversion, leading to widespread adoption in electricity production and naval propulsion.

Throughout the 20th century, steam turbine technology advanced rapidly, with improvements in blade design, steam conditions, and manufacturing processes. The introduction of superheated steam significantly increased efficiency by reducing moisture content and improving energy extraction. Multi-stage turbines, reheat cycles, and condensing systems further enhanced performance, making steam turbines the dominant technology in large-scale power plants. The expansion of fossil-fuel and nuclear power plants in the mid-20th century further drove the development of high-capacity steam turbines, with units exceeding 1,000 megawatts in output.

In recent decades, research has focused on increasing efficiency and sustainability. The development of ultra-supercritical and advanced ultra-supercritical steam turbines, operating at pressures above 250 bar and temperatures over 600°C, has pushed efficiency levels beyond 45%, reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Modern computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and finite element analysis (FEA) are now used to optimize blade aerodynamics and reduce energy losses. Digital monitoring and AI-driven predictive maintenance have further improved reliability, reducing operational costs and extending turbine lifespans.

Looking ahead, future developments in steam turbine technology will focus on integrating renewable energy sources, improving materials through advanced coatings and additive manufacturing, and enhancing environmental performance through carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems. As global energy demand continues to evolve, steam turbines remain a cornerstone of efficient power generation, with continuous innovation ensuring their role in both traditional and sustainable energy systems.

The continuous development of steam turbines has been driven by the need for higher efficiency, durability, and adaptability in power generation and industrial applications. One of the key factors in this evolution has been the improvement of materials used in turbine construction. Early steam turbines relied on carbon steel, but as steam conditions became more extreme, high-strength alloys, stainless steel, and nickel-based superalloys were introduced to withstand high temperatures and pressures. Modern turbines utilize advanced coatings, such as thermal barrier coatings, to protect blades from erosion, corrosion, and thermal fatigue, extending their operational lifespan.

Another major advancement has been the refinement of blade design and steam flow optimization. The introduction of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has allowed engineers to create highly efficient blade profiles that maximize energy extraction while minimizing losses. In multi-stage turbines, carefully designed reaction and impulse blades work together to ensure a smooth and efficient transfer of kinetic energy from steam to the rotor. The development of longer last-stage blades has also improved the performance of low-pressure sections, allowing more energy to be extracted from exhaust steam before it reaches the condenser.

Reheat and regenerative cycles have played a crucial role in increasing the efficiency of steam turbines. In a reheat cycle, steam is expanded in the high-pressure turbine, reheated in the boiler, and then expanded further in the intermediate and low-pressure turbines. This process reduces moisture content in the later stages, improving efficiency and preventing blade erosion. Regenerative feedwater heating, where steam is extracted from intermediate stages to preheat the feedwater, also enhances overall plant efficiency by reducing the fuel required to generate steam.

Automation and digital monitoring systems have revolutionized steam turbine operation and maintenance. Real-time data collection through smart sensors allows for precise control of steam flow, pressure, and temperature, ensuring optimal performance under varying load conditions. Predictive maintenance techniques, enabled by machine learning and artificial intelligence, analyze operational data to detect potential failures before they occur, reducing unplanned downtime and maintenance costs. Digital twins, virtual models of steam turbines, are now used to simulate different operating scenarios, optimize performance, and improve reliability.

These continuous advancements in materials, blade design, thermodynamic cycles, and digital monitoring have made modern steam turbines more efficient and reliable than ever before. As the global energy industry shifts toward cleaner and more sustainable technologies, steam turbines are evolving to integrate with renewable energy sources, carbon capture systems, and hybrid power generation solutions. Their long history of innovation ensures they will remain a key technology in energy production for decades to come.

The efficiency improvements and technological advancements in steam turbines have also been driven by the increasing demand for sustainable and cleaner energy solutions. One of the most significant developments in recent years has been the move toward ultra-supercritical (USC) and advanced ultra-supercritical (A-USC) steam conditions. These turbines operate at pressures above 300 bar and temperatures exceeding 700°C, significantly improving thermal efficiency beyond 45%, reducing fuel consumption, and lowering carbon emissions. The materials used in these high-temperature turbines include nickel-based alloys and advanced ceramics, which can withstand extreme thermal stresses and prolong operational life.

The integration of steam turbines with renewable energy sources has expanded their role in modern power generation. In biomass and waste-to-energy plants, steam turbines convert heat from combustion into electricity, providing a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels. Similarly, in solar thermal power plants, steam turbines use heat collected from concentrated solar energy to generate electricity, improving efficiency and grid stability. Hybrid power plants, which combine steam turbines with other energy sources such as gas turbines or solar energy, offer flexible and efficient energy solutions by optimizing heat utilization across multiple systems.

Another key development in steam turbine technology is the implementation of highly flexible operational strategies to accommodate varying energy demands. Traditionally, steam turbines operate most efficiently at full load, but modern control systems allow them to adjust to partial load conditions without significant efficiency losses. This is particularly important in power grids with high levels of intermittent renewable energy, where steam turbines must ramp up or down to balance fluctuations in wind and solar power. Fast-start turbines and sliding-pressure operation techniques have been developed to enhance the load-following capabilities of steam turbines, making them more adaptable to modern energy grids.

The role of digitalization in steam turbine operation continues to expand, with advanced monitoring systems enabling real-time optimization and predictive maintenance. Digital twin technology, which creates a virtual replica of a turbine, allows engineers to simulate operating conditions, predict performance trends, and optimize maintenance schedules. AI-driven analytics assess sensor data to detect early signs of wear, misalignment, or inefficiencies, allowing operators to take corrective action before failures occur. Remote monitoring and control systems enable plant operators to manage turbine performance from centralized locations, improving efficiency and reducing the need for on-site interventions.

As global energy priorities shift toward sustainability and efficiency, steam turbines are being integrated with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil-fuel power plants. These systems capture CO₂ from flue gases before it is released into the atmosphere, allowing steam power plants to operate with a lower environmental impact. Research into closed-loop supercritical CO₂ (sCO₂) cycles, which use CO₂ instead of steam as a working fluid, is also gaining attention as a potential next-generation alternative to traditional steam cycles, offering higher efficiency and lower emissions.

With ongoing innovations in materials, digital technologies, and hybrid energy systems, steam turbines continue to evolve to meet the demands of a changing energy landscape. Their ability to integrate with renewable sources, operate under extreme conditions, and provide reliable power generation ensures that they will remain a critical component of global energy infrastructure for decades to come.

The future of steam turbine technology is centered around continued advancements in efficiency, flexibility, and environmental sustainability. One of the key areas of development is in supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO₂) cycles, which offer a potential breakthrough in energy conversion efficiency. Unlike traditional steam cycles, sCO₂ operates at high pressures and densities, allowing for more compact and efficient turbine designs. These systems have the potential to increase efficiency by 5–10% compared to conventional Rankine cycles, while also reducing water consumption—a major advantage in arid regions where water-intensive cooling systems are a concern.

In addition to sCO₂, hydrogen co-firing and ammonia-based combustion systems are being explored as low-carbon alternatives for steam generation. By integrating hydrogen or ammonia as fuels in power plants, steam turbines can operate with significantly reduced CO₂ emissions while maintaining high efficiency. These developments align with global decarbonization efforts and the transition toward cleaner energy sources. Hybrid power plants, where steam turbines work in tandem with renewable energy sources like solar thermal and geothermal, further enhance their role in sustainable energy systems.

The evolution of steam turbine materials and manufacturing techniques is another major area of innovation. Advanced ceramic coatings, additive manufacturing (3D printing), and new high-temperature alloys are being developed to extend turbine lifespan and improve resistance to wear, erosion, and thermal fatigue. 3D printing enables the production of complex turbine blade geometries that optimize aerodynamics and heat resistance, allowing for higher efficiency and lower maintenance costs.

Automation and AI-driven optimization are also transforming how steam turbines operate. Real-time performance monitoring, powered by digital twins and IoT-connected sensors, enables predictive maintenance and continuous efficiency improvements. AI algorithms analyze operating conditions and suggest adjustments to optimize steam flow, load distribution, and temperature control, reducing energy losses and extending component life. These technologies are making steam turbines more adaptable to dynamic power grid demands, ensuring their continued relevance in modern energy systems.

Looking further into the future, research into closed-loop high-efficiency energy systems, such as combined Brayton-Rankine cycles and waste heat recovery solutions, is gaining momentum. These systems aim to recover and utilize as much waste heat as possible, maximizing overall plant efficiency. Coupled with carbon capture technologies, steam turbines will play a crucial role in bridging the gap between current energy infrastructure and a low-carbon future.

As global energy needs evolve, steam turbines remain at the forefront of power generation innovation. Whether through advanced thermodynamic cycles, improved materials, or AI-driven optimization, these machines will continue to adapt to new challenges and play a vital role in providing reliable, efficient, and sustainable energy worldwide.

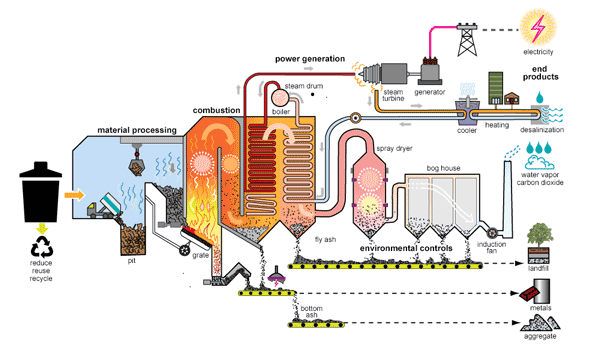

How do steam power plants work

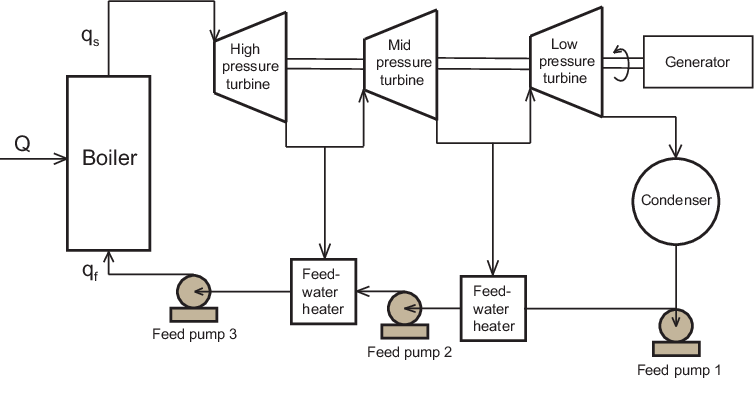

Steam power plants generate electricity by converting thermal energy from fuel combustion into mechanical energy using steam turbines. The process follows the Rankine cycle, a thermodynamic cycle that efficiently converts heat into work. The key components and working principles of a steam power plant are as follows:

1. Fuel Combustion and Steam Generation

The process begins with a boiler or steam generator, where fuel (coal, natural gas, biomass, or nuclear energy) is burned to produce heat. In nuclear power plants, heat is generated by nuclear fission rather than combustion. The heat converts water into high-pressure, high-temperature steam. Superheaters may be used to further increase steam temperature, improving efficiency and reducing moisture content in later stages.

2. Expansion in the Steam Turbine

The high-pressure steam is directed to a steam turbine, where it expands and pushes turbine blades, causing the rotor to spin. This conversion of thermal energy into mechanical work is highly efficient in multi-stage turbines, where steam passes through high-pressure (HP), intermediate-pressure (IP), and low-pressure (LP) turbine stages before exiting. The rotational motion of the turbine shaft is used to drive a generator to produce electricity.

3. Electricity Generation

The turbine is connected to an electric generator, which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy using electromagnetic induction. The spinning turbine shaft rotates a coil of wire within a magnetic field, generating alternating current (AC) electricity, which is then sent to a transformer for voltage regulation and distribution.

4. Steam Condensation and Recycling

After passing through the turbine, the low-pressure steam enters a condenser, where it is cooled using a cooling system (air-cooled or water-cooled). The steam condenses back into water and is collected in a hot well. This condensate is then pumped back to the boiler by a feedwater pump, completing the closed-loop cycle. In many power plants, feedwater heaters improve efficiency by preheating the water using steam extracted from the turbine.

5. Waste Heat Management and Environmental Controls

Steam power plants generate waste heat, which is either released into the atmosphere or utilized in cogeneration (CHP) systems, where excess heat is used for district heating, desalination, or industrial processes. Modern power plants also employ pollution control technologies, such as electrostatic precipitators, scrubbers, and carbon capture systems, to reduce emissions and improve environmental performance.

Efficiency Enhancements

Modern steam power plants implement several strategies to increase efficiency:

- Supercritical and ultra-supercritical steam cycles operate at extremely high pressures and temperatures to maximize thermal efficiency.

- Reheating and regenerative feedwater heating reduce steam moisture content and improve heat utilization.

- Digital monitoring and automation optimize plant operations, enabling real-time performance adjustments and predictive maintenance.

Applications and Importance

Steam power plants play a crucial role in global electricity generation, providing reliable base-load power for grids. They are used in fossil-fuel, biomass, geothermal, solar thermal, and nuclear power stations. As technology advances, steam power plants are being integrated with renewable energy and carbon capture systems to enhance sustainability and reduce their environmental impact.

The efficiency and reliability of steam power plants have been continuously improved through advancements in technology, thermodynamic cycle enhancements, and material innovations. One of the most significant developments in modern steam power plants is the use of supercritical and ultra-supercritical (USC) steam conditions. Unlike conventional subcritical power plants, where steam exists as a mixture of liquid and gas, supercritical power plants operate at pressures above 22.1 MPa (the critical point of water), where steam directly transitions into a high-energy gas phase. Ultra-supercritical plants push these limits even further, with operating temperatures exceeding 600°C. These advancements significantly increase thermal efficiency, reducing fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions.

Reheat and regenerative cycles also play a crucial role in improving efficiency. In a reheat cycle, steam is expanded in the high-pressure turbine, reheated in the boiler, and then sent to the intermediate and low-pressure turbines for further expansion. This reduces steam moisture content and prevents blade erosion while improving overall energy extraction. Regenerative feedwater heating, where some steam is extracted from intermediate turbine stages to preheat the feedwater before it enters the boiler, further enhances efficiency by reducing the energy required for steam generation.

Material advancements have been critical to enabling these high-efficiency power plants. Nickel-based superalloys, high-chromium steels, and ceramic coatings have been developed to withstand extreme temperatures and pressures, increasing the durability and reliability of turbine components. Advanced blade design and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling allow for optimized steam flow, reducing aerodynamic losses and increasing overall turbine performance. Longer last-stage blades have also been introduced in low-pressure sections to improve energy extraction from exhaust steam.

Automation and digital monitoring systems have transformed steam power plant operation and maintenance. Internet of Things (IoT) sensors continuously monitor critical parameters such as steam temperature, pressure, and turbine vibration, providing real-time data to plant operators. AI-driven predictive maintenance detects early signs of wear and inefficiencies, reducing downtime and maintenance costs. The use of digital twins—virtual models of steam power plants—allows engineers to simulate operating conditions and optimize performance before making real-world adjustments.

In terms of environmental impact, modern steam power plants are increasingly adopting carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to reduce CO₂ emissions. By capturing and storing carbon emissions from flue gases, these plants can continue to provide reliable electricity while minimizing their contribution to climate change. Integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) technology, which converts coal into synthetic gas before combustion, further enhances efficiency and reduces pollutant emissions.

Looking ahead, the integration of steam turbines with renewable energy sources such as biomass, solar thermal, and geothermal power is expanding their role in sustainable energy generation. Hybrid systems, where steam turbines operate alongside gas turbines or renewable energy sources, allow for greater flexibility in power generation, improving grid stability. Additionally, emerging technologies like supercritical CO₂ (sCO₂) cycles promise to further enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impact by using CO₂ instead of water as the working fluid.

With continuous advancements in thermodynamics, materials science, and digitalization, steam power plants remain a cornerstone of global energy infrastructure. As new technologies emerge, their efficiency, flexibility, and environmental performance will continue to improve, ensuring their relevance in the evolving energy landscape.

The future of steam power plants is being shaped by cutting-edge advancements in efficiency, sustainability, and flexibility. One of the most promising developments is the adoption of supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO₂) power cycles, which offer significant advantages over traditional steam cycles. Unlike water-based steam cycles, sCO₂ operates at higher densities and pressures, allowing for more compact turbine designs and higher thermal efficiency. This technology reduces energy losses, enhances power plant flexibility, and minimizes water consumption, making it particularly valuable in regions with water scarcity. Research is ongoing to integrate sCO₂ cycles into next-generation power plants, including nuclear and solar thermal applications.

The use of hydrogen as a fuel source is also gaining attention in steam power generation. Hydrogen can be co-fired with fossil fuels or used as a primary fuel in modified boilers, producing steam with little to no carbon emissions. Hydrogen-based steam power plants could become a key component of decarbonized energy systems, particularly in conjunction with renewable hydrogen production via electrolysis. Ammonia-fueled power plants are another emerging concept, as ammonia can be used as a hydrogen carrier and combusted to generate heat for steam production while minimizing carbon emissions.

Hybrid power plants, which combine steam turbines with other energy sources, are becoming more common as energy grids transition toward renewable energy. In solar thermal power plants, steam turbines convert heat from concentrated solar energy into electricity, allowing for energy storage and grid stability. Geothermal power plants use naturally occurring steam or hot water from deep underground reservoirs to drive turbines, providing a continuous and renewable energy source. Hybrid gas-steam plants, utilizing combined-cycle configurations, optimize fuel usage by running both gas and steam turbines from a single fuel source, improving overall efficiency.

Another key area of innovation is advanced waste heat recovery systems. Many industrial processes produce large amounts of unused heat, which can be captured and used to generate steam for power production. Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) systems allow low-temperature waste heat to be converted into electricity using organic working fluids instead of water, enabling power generation from sources that were previously considered inefficient. Waste heat recovery is especially valuable in industries such as steel manufacturing, cement production, and chemical processing, where excess heat is abundant.

As energy demand fluctuates due to increased renewable energy integration, modern steam power plants are adopting flexible operating strategies to enhance grid reliability. Sliding pressure operation, fast-start technologies, and variable load adjustments allow steam turbines to ramp up or down quickly in response to changing energy demands. This adaptability makes steam power plants crucial for balancing renewable energy fluctuations, ensuring a stable power supply even when solar or wind generation varies.

The role of digitalization and artificial intelligence (AI) in optimizing steam power plant performance continues to grow. AI-driven control systems analyze real-time data from IoT-connected sensors to optimize fuel combustion, steam flow, and turbine efficiency. Digital twins simulate plant operations, allowing engineers to test different scenarios, predict maintenance needs, and improve overall performance without disrupting actual plant operations. These technologies help reduce downtime, lower maintenance costs, and extend the lifespan of critical components.

Looking ahead, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies will play an essential role in making steam power plants more sustainable. By capturing CO₂ emissions from flue gases and either storing it underground or converting it into useful products, CCUS can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of fossil-fuel-based steam power plants. The combination of CCUS with biomass power generation (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage, or BECCS) even has the potential to create carbon-negative power plants, removing more CO₂ from the atmosphere than they emit.

With continuous advancements in high-efficiency materials, hybrid energy systems, digital monitoring, and carbon reduction technologies, steam power plants are evolving to meet the needs of a cleaner and more flexible energy future. While traditional coal-fired plants are being phased out in many regions, next-generation steam power technologies will remain a critical part of the global energy mix, ensuring efficiency, reliability, and sustainability in an increasingly decarbonized world.

As steam power plants continue to evolve, several emerging technologies and research areas are shaping their future. One of the most promising developments is closed-loop supercritical CO₂ (sCO₂) power cycles, which can operate at much higher efficiencies than traditional Rankine cycles. These systems use CO₂ instead of water as the working fluid, allowing for more compact turbines, reduced water usage, and improved thermal efficiency. Research is ongoing to integrate sCO₂ cycles into both fossil-fuel and renewable energy systems, particularly in nuclear power plants, solar thermal plants, and waste heat recovery applications.

Another transformative advancement is the integration of advanced energy storage technologies with steam power plants. Thermal energy storage (TES) systems allow excess heat to be stored in materials such as molten salts or phase-change materials, which can later be used to generate steam when electricity demand is high. This makes steam power plants more flexible and better suited for balancing intermittent renewable energy sources like solar and wind. Pumped heat energy storage (PHES) is also being explored, where excess electricity is converted into heat and stored in solid materials before being converted back into steam-based electricity when needed.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are playing an increasing role in improving steam power plant performance. AI-driven algorithms analyze real-time data from turbines, boilers, and condensers to optimize energy efficiency, predict equipment failures, and automate operational adjustments. Self-learning control systems can dynamically optimize steam pressure, temperature, and fuel combustion, ensuring that power plants run at peak efficiency under varying load conditions. Digital twin technology, which creates virtual models of power plants, allows operators to test different scenarios, optimize performance, and predict maintenance needs without disrupting actual plant operations.

In the pursuit of sustainability, zero-emission steam power plants are being explored using hydrogen combustion, ammonia-based fuels, and biomass gasification. Hydrogen-fueled steam turbines are gaining attention due to their ability to produce steam without carbon emissions. Similarly, ammonia—a hydrogen carrier—can be burned in high-temperature steam boilers with minimal greenhouse gas emissions. Biomass-based steam power plants, when combined with carbon capture technologies (BECCS), offer the potential for negative carbon emissions, meaning they can remove CO₂ from the atmosphere while generating electricity.

Hybridization with renewable energy sources is also expanding. Geothermal and solar thermal power plants use steam turbines in conjunction with naturally occurring heat sources, providing low-carbon and continuous power generation. Hybrid gas-steam combined cycle plants maximize efficiency by utilizing waste heat from gas turbines to generate steam for additional power generation. These hybrid approaches are being designed to work with renewable hydrogen, waste heat recovery, and concentrated solar power (CSP) systems to create fully decarbonized energy solutions.

Advancements in steam turbine materials and manufacturing techniques are further pushing efficiency boundaries. The use of nickel-based superalloys, advanced ceramic coatings, and additive manufacturing (3D printing) enables turbine components to withstand extreme temperatures and pressures, extending their operational lifespan and reducing maintenance costs. Aerodynamic blade design improvements, made possible through computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, are optimizing steam flow and reducing energy losses.

As power grids continue to evolve, flexible steam turbine operation is becoming increasingly important. Traditionally, steam turbines operated best at full load, but modern designs now allow for fast start-up, sliding pressure operation, and rapid load changes to accommodate variable renewable energy generation. These features make steam power plants more adaptable to modern grid requirements, improving overall system stability.

With ongoing innovations in advanced thermodynamic cycles, energy storage, digitalization, and clean energy integration, steam power plants are positioned to remain a key player in the global energy transition. As new technologies continue to emerge, the next generation of steam power plants will be more efficient, environmentally sustainable, and better suited for a flexible and decarbonized energy landscape.

Main parts of turbine

A steam turbine consists of several key components, each playing a critical role in converting thermal energy from steam into mechanical power. The main parts of a steam turbine include:

1. Rotor

The rotor is the rotating component of the turbine that carries the turbine blades and is connected to the generator shaft. It converts the kinetic energy of steam into rotational mechanical energy. The rotor must be precisely balanced to ensure smooth operation and minimize vibration.

2. Blades (Buckets)

Turbine blades, also called buckets, are mounted on the rotor and are responsible for extracting energy from high-pressure steam. They come in two main types:

- Impulse blades: Used in impulse turbines, these blades change the direction of high-velocity steam jets, causing the rotor to spin.

- Reaction blades: Used in reaction turbines, these blades experience both steam pressure and velocity changes, producing additional rotational force.

3. Casing (Cylinder)

The casing encloses the rotor and blades, directing steam flow through the turbine. It is typically divided into high-pressure, intermediate-pressure, and low-pressure sections. The casing must withstand high temperatures and pressures while minimizing heat losses.

4. Nozzles

Nozzles are responsible for directing and accelerating the steam onto the turbine blades. They convert thermal energy into kinetic energy by reducing the steam pressure and increasing velocity before it reaches the rotor. Nozzles are used mainly in impulse turbines.

5. Bearings

Bearings support the turbine rotor and allow it to rotate smoothly. There are two main types:

- Journal bearings: Support radial loads and help maintain shaft alignment.

- Thrust bearings: Absorb axial forces and prevent the rotor from moving along its axis.

6. Shaft

The shaft transmits rotational energy from the rotor to the generator or mechanical load. It must be precisely machined to ensure efficient power transfer with minimal friction losses.

7. Steam Chest and Control Valves

The steam chest is the section where steam enters the turbine. It contains control valves, which regulate steam flow and pressure to ensure optimal turbine performance. Control valves include stop valves, which shut off steam flow, and governor valves, which adjust steam input based on load demand.

8. Glands and Seals

To prevent steam leakage and maintain efficiency, turbines use gland seals at shaft entry and exit points. These seals prevent high-pressure steam from escaping while also keeping air from entering low-pressure sections. Labyrinth seals and carbon ring seals are commonly used in steam turbines.

9. Exhaust System and Condenser

After expanding through the turbine, low-pressure steam exits through the exhaust system and enters the condenser, where it is cooled and converted back into water. The condenser improves efficiency by maintaining a low back-pressure at the turbine exhaust.

10. Governor System

The governor system automatically controls the steam flow to maintain a constant turbine speed, adjusting for load variations. It prevents overspeed conditions and ensures stable operation by modulating the control valves.

11. Coupling

The coupling connects the turbine shaft to the generator or driven equipment, transmitting mechanical power. It must be flexible enough to accommodate slight misalignments while maintaining efficient power transfer.

Each of these components plays a crucial role in the operation and efficiency of a steam turbine, ensuring reliable power generation in various industrial and power plant applications.

The performance and reliability of a steam turbine depend on the precise design, material selection, and maintenance of its key components. Each part undergoes significant mechanical, thermal, and aerodynamic stresses during operation, requiring careful engineering and monitoring.

Rotor and Blades

The rotor is typically made from high-strength alloy steels to withstand the immense rotational forces and thermal stresses. It is machined to extremely tight tolerances to ensure balance and smooth operation. The blades, often made from nickel-based superalloys or titanium alloys, must endure high temperatures and steam velocities without deformation or fatigue. To enhance performance, modern turbines use shrouded blades (connected at the tips) or free-standing blades depending on efficiency requirements. Last-stage blades (LSBs) in low-pressure turbines are the longest and most crucial, designed aerodynamically to handle high-speed exhaust steam while minimizing energy losses.

Casing and Sealing Systems

The casing, usually constructed from cast steel or welded steel plates, contains steam at different pressure levels. It is insulated to reduce heat losses and maintain efficiency. The casing also incorporates expansion joints to accommodate thermal expansion and contraction during load variations. Sealing systems, such as labyrinth seals and brush seals, prevent steam leakage along the rotor shaft. In high-performance turbines, advanced sealing materials, such as carbon fiber composites, improve efficiency by minimizing leakage losses.

Bearings and Shaft

Bearings support the rotor’s weight and maintain alignment. Hydrodynamic bearings, lubricated with oil, reduce friction and dissipate heat generated during operation. Magnetic bearings are being explored in modern designs for even lower friction and improved performance. The shaft, made from forged steel, must be perfectly aligned with the generator to prevent excessive vibrations and ensure smooth power transmission.

Steam Chest and Control Valves

The steam chest directs incoming steam to the turbine through precisely controlled stop valves and governor valves. These components regulate steam pressure and flow, ensuring stable turbine speed under varying load conditions. Fast-acting emergency stop valves (ESVs) are critical safety features that shut off steam supply in case of an overspeed event or system failure.

Condenser and Exhaust System

The exhaust system directs low-pressure steam to the condenser, where it is cooled and converted back into water for reuse in the boiler. The condenser operates under vacuum conditions, created by air ejectors or vacuum pumps, to maximize turbine efficiency. Cooling water circulation systems maintain optimal condensation temperatures, using either natural water sources (once-through cooling) or cooling towers for recirculated cooling.

Governor System and Automation

The governor system is an essential control mechanism that adjusts steam flow to match electrical load demand. Modern turbines use electronic and hydraulic governors integrated with programmable logic controllers (PLCs) for precise speed and load control. Advanced power plants use AI-driven predictive analytics to optimize governor responses, reducing fluctuations and improving grid stability.

Maintenance and Performance Optimization

Regular maintenance is crucial to ensure long-term turbine efficiency. Condition monitoring systems (CMS) use vibration analysis, temperature sensors, and acoustic emissions to detect early signs of wear or misalignment. Remote monitoring technologies, connected through Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) platforms, provide real-time data on turbine health, allowing predictive maintenance and minimizing unplanned downtime.

Future Innovations