Coppus Steam Turbine: The Coppus steam turbine is a specialized industrial turbine best known for its reliability, simplicity, and long service life. It has been widely used in refineries, chemical plants, pulp and paper mills, steel plants, and other heavy industrial facilities where steam is already available as part of the process. Rather than being designed for large-scale power generation like utility turbines, Coppus turbines are primarily intended for mechanical drive applications and modest electrical generation within industrial plants.

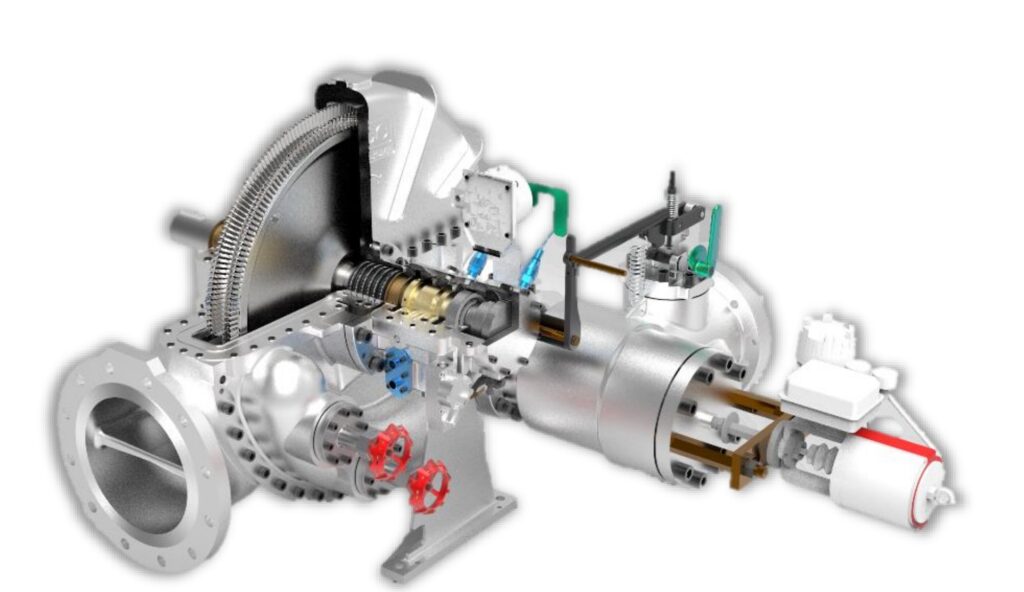

At its core, a Coppus steam turbine converts the thermal energy of steam into rotational mechanical energy. High-pressure steam enters the turbine and expands through a series of nozzles, accelerating as it does so. This high-velocity steam is directed onto turbine blades mounted on a rotating shaft. As the steam changes direction and velocity while passing over the blades, it transfers energy to the rotor, causing it to spin. The rotating shaft can then be connected directly to equipment such as pumps, compressors, blowers, fans, or generators.

One of the defining characteristics of Coppus steam turbines is their rugged mechanical design. They are typically built as single-stage or simple multi-stage impulse turbines. This design choice reduces complexity and makes the machines easier to maintain compared to large reaction turbines used in power stations. The impulse principle means that most of the pressure drop occurs in the stationary nozzles, while the moving blades primarily extract kinetic energy from the steam jet. This approach is well suited to industrial environments where steam conditions may vary and where absolute efficiency is less critical than reliability and durability.

Coppus turbines are commonly used as back-pressure or condensing turbines, depending on the needs of the process. In back-pressure operation, steam exits the turbine at a controlled pressure and is then used for heating or other process requirements. This allows plants to extract useful mechanical work from steam while still meeting downstream thermal needs. In condensing operation, the exhaust steam is routed to a condenser where it is cooled and converted back into water, allowing for greater energy extraction but requiring additional equipment.

Another important feature of Coppus turbines is their ability to operate over a wide range of steam pressures and flow rates. Industrial steam systems are often subject to fluctuations caused by changing process demands. Coppus turbines are designed to tolerate these variations without excessive wear or loss of stability. Governors and control valves regulate steam admission to maintain the desired speed or power output, even when inlet conditions change.

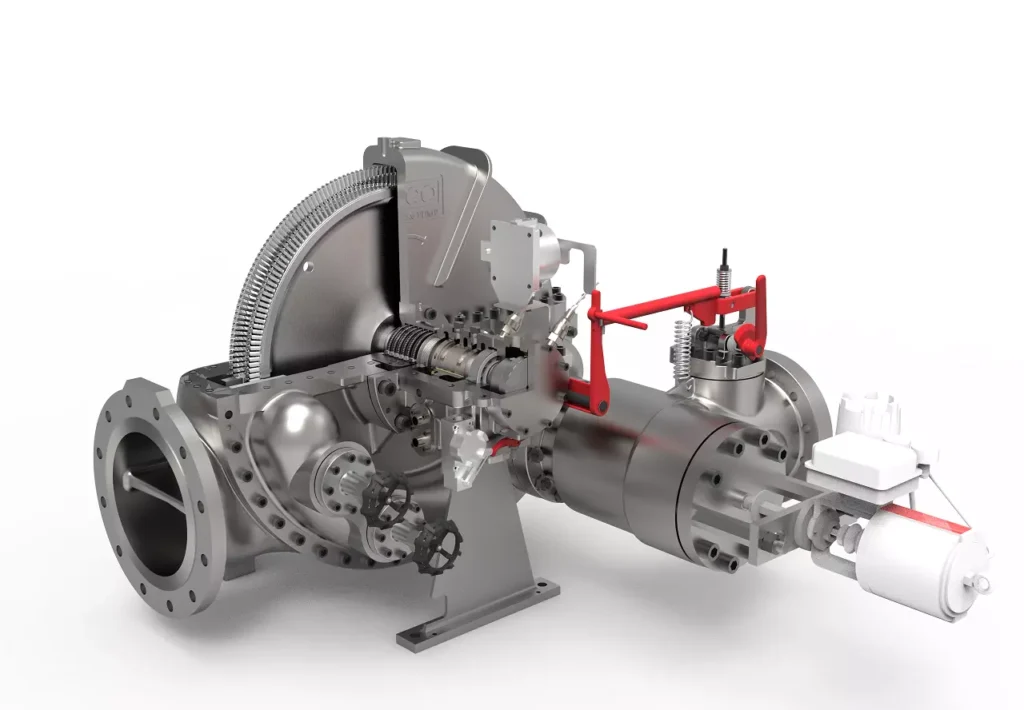

Speed control is a critical aspect of steam turbine operation, especially for mechanical drives. Coppus turbines often use mechanical or hydraulic governors that respond quickly to load changes. When the driven equipment demands more power, the governor opens the steam valve to admit more steam. When demand decreases, the valve closes accordingly. This direct and responsive control system helps protect both the turbine and the driven machinery from overspeed or sudden load loss.

From a construction standpoint, Coppus turbines are typically built with heavy casings, robust shafts, and generously sized bearings. These features contribute to their long operating life. Many Coppus turbines remain in service for decades, often outlasting the original process equipment they were installed to drive. Routine maintenance usually focuses on bearings, seals, control mechanisms, and periodic inspection of nozzles and blades.

Maintenance requirements are generally modest compared to more complex turbine systems. Because the design is relatively simple, plant maintenance personnel can often perform inspections and minor repairs without specialized tools or extensive downtime. This has made Coppus turbines particularly attractive in facilities where continuous operation is essential and shutdowns are costly.

Another reason for their continued use is their compatibility with existing steam systems. Many industrial plants generate steam as a byproduct of other operations, such as boilers used for heating or chemical reactions. Installing a Coppus steam turbine allows plants to recover energy that would otherwise be wasted through pressure reduction valves. In this role, the turbine functions as an energy recovery device, improving overall plant efficiency without requiring major changes to the steam infrastructure.

Although newer technologies such as electric variable-speed drives and gas turbines have replaced steam turbines in some applications, Coppus turbines remain relevant in industries where steam is abundant and reliable. They are especially valued in environments where electrical power may be expensive, unreliable, or where mechanical drive offers advantages in simplicity and robustness.

In summary, the Coppus steam turbine represents a practical and proven approach to industrial energy conversion. It is not designed to achieve the highest possible thermal efficiency, but rather to deliver dependable mechanical power under demanding conditions. Its straightforward impulse design, tolerance for variable steam conditions, ease of maintenance, and long service life have made it a trusted piece of equipment in industrial plants around the world. Even in modern facilities, Coppus turbines continue to play a quiet but important role in converting steam into useful work.

Another notable aspect of Coppus steam turbines is their adaptability to different installation layouts and operating philosophies. They can be mounted horizontally or vertically, depending on space constraints and the nature of the driven equipment. In older plants, it is common to find Coppus turbines installed in tight mechanical rooms or integrated directly into process lines where space efficiency mattered as much as performance. This flexibility made them a practical choice during periods of rapid industrial expansion when plants were designed around function rather than uniform standards.

The materials used in Coppus steam turbines are selected to withstand harsh operating environments. Steam in industrial settings is not always perfectly clean or dry. It may carry small amounts of moisture, scale, or chemical contaminants. Coppus turbines are built with blade and nozzle materials that resist erosion and corrosion, helping maintain performance over long periods. While poor steam quality will still increase wear, these turbines tend to degrade gradually rather than fail suddenly, giving operators time to plan maintenance.

Sealing systems in Coppus turbines are typically straightforward, relying on labyrinth seals rather than complex mechanical seals. Labyrinth seals reduce steam leakage along the shaft while avoiding direct contact between rotating and stationary parts. This design minimizes friction and wear, which is especially important for machines expected to run continuously for years. Even as seals wear over time, performance loss is usually modest and predictable.

Bearings are another area where Coppus turbines emphasize durability over sophistication. Most units use plain journal bearings lubricated by oil systems that are simple and easy to monitor. These bearings can tolerate high loads and minor misalignment, which is valuable in industrial settings where foundations may settle or connected equipment may introduce vibration. With proper lubrication and temperature monitoring, bearing failures are relatively rare.

Coppus turbines are also known for their straightforward startup and shutdown procedures. Unlike large power-generation turbines that require long warm-up times and strict thermal management, Coppus turbines can often be brought online relatively quickly. Operators still need to follow proper procedures to avoid thermal shock, but the machines are forgiving enough to accommodate the realities of industrial operation. This makes them well suited to plants where steam availability or process demand can change on short notice.

In terms of efficiency, Coppus turbines are optimized for reliability and flexibility rather than peak performance. Their efficiency is generally lower than that of modern, high-stage turbines, especially at partial loads. However, in many applications, the steam used by the turbine would otherwise be throttled or vented. In those cases, even a modestly efficient turbine represents a net gain in energy utilization. This perspective has kept Coppus turbines relevant in energy-conscious facilities focused on reducing waste rather than achieving textbook efficiency numbers.

Noise and vibration characteristics are another practical consideration. Coppus turbines are typically quieter and smoother than many alternative prime movers, particularly large reciprocating engines. Properly maintained units operate with steady rotation and minimal vibration, which reduces stress on foundations and connected machinery. This contributes to lower long-term maintenance costs across the entire drive system.

Over time, Coppus has developed a wide range of turbine sizes and ratings to match different applications. Smaller units may produce only a few hundred horsepower, while larger industrial models can deliver several thousand horsepower. This range allows plants to standardize on a familiar technology across multiple processes, simplifying training, spare parts inventory, and maintenance practices.

Modern Coppus turbines may incorporate updated control systems while retaining the core mechanical design. Electronic governors, improved instrumentation, and enhanced safety systems can be added to meet current operational and regulatory requirements. These updates allow older turbine concepts to integrate smoothly into modern control rooms without sacrificing the robustness that made them valuable in the first place.

Safety is an essential consideration in steam turbine operation, and Coppus turbines include features to protect both equipment and personnel. Overspeed trip mechanisms are standard, ensuring that the turbine shuts down automatically if rotational speed exceeds safe limits. Relief valves, protective casings, and clear operating procedures further reduce risk in high-energy steam environments.

In many plants, Coppus steam turbines have become part of the institutional memory. Operators and maintenance technicians often trust them because they understand how they behave under stress and how they fail when problems arise. This familiarity can be just as important as technical specifications, especially in facilities where downtime has serious economic consequences.

Overall, the continued use of Coppus steam turbines reflects a broader industrial reality. In environments where steam is readily available, conditions are demanding, and simplicity matters, these turbines offer a dependable solution. They may not be flashy or cutting-edge, but they perform their role consistently and predictably. That quiet reliability is the reason Coppus steam turbines remain in service long after many newer technologies have come and gone.

The role of Coppus steam turbines in energy recovery deserves special attention. In many industrial plants, steam pressure must be reduced to meet process requirements. Traditionally, this reduction is handled by pressure-reducing valves, which dissipate excess energy as heat and noise. By replacing or supplementing these valves with a Coppus steam turbine, plants can convert otherwise wasted pressure energy into useful mechanical or electrical power. This approach improves overall plant efficiency without increasing fuel consumption in the boiler.

In these energy recovery applications, Coppus turbines often operate continuously at steady conditions. This type of service suits their design philosophy well. The turbine runs at a constant speed, driving a generator or mechanical load while exhausting steam at a pressure suitable for downstream use. Because the turbine is not required to follow rapid load changes, mechanical stress is reduced, further extending service life.

Another important application is emergency or backup power generation. In facilities where steam is available even during electrical outages, a Coppus turbine can drive an essential pump or generator to support safe shutdown procedures. This capability is especially valuable in refineries and chemical plants, where loss of circulation or cooling can quickly become hazardous. The independence from external electrical supplies adds a layer of resilience to plant operations.

From an operational standpoint, operators often appreciate the predictability of Coppus turbines. Their response to changes in steam flow, load, or pressure is gradual and easy to observe. This allows experienced personnel to diagnose developing issues by sound, vibration, or temperature trends. Subtle changes in operating behavior can signal nozzle fouling, bearing wear, or governor issues long before a serious failure occurs.

The longevity of Coppus turbines also means that many units in service today were manufactured decades ago. This creates both challenges and advantages. On the challenge side, older machines may lack modern instrumentation or safety features. On the advantage side, their simple construction makes retrofitting feasible. Temperature sensors, vibration monitors, and electronic controls can often be added without major redesign. This ability to modernize extends the useful life of existing equipment and avoids the cost of full replacement.

Spare parts availability is another practical concern. Coppus turbines are designed with standardized components wherever possible. Nozzles, blades, bearings, and seals follow established patterns rather than highly customized designs. This simplifies fabrication and repair, even when original parts are no longer readily available. In many cases, local machine shops can produce replacement components based on drawings or worn samples.

Training requirements for Coppus turbines are relatively modest. Operators do not need advanced turbine theory to run them safely and effectively. Basic understanding of steam conditions, lubrication, speed control, and safety interlocks is usually sufficient. This makes Coppus turbines suitable for plants with limited access to specialized turbine engineers.

Environmental considerations also play a role in their continued use. Steam turbines produce no direct combustion emissions at the point of use. When driven by steam generated from waste heat or byproduct fuels, the overall environmental impact can be significantly lower than that of alternative prime movers. In energy recovery installations, the turbine effectively reduces waste, aligning with modern sustainability goals even though the technology itself is not new.

It is also worth noting that Coppus turbines are often conservative in their ratings. Nameplate power and speed limits typically include generous safety margins. This conservative approach reduces the likelihood of overstressing components during abnormal operation. While it may result in slightly larger or heavier machines, the trade-off favors reliability and long-term stability.

In real-world plant conditions, this conservative design philosophy pays off. Coppus turbines tend to tolerate operator error, transient upsets, and imperfect maintenance better than more tightly optimized machines. This tolerance does not eliminate the need for proper care, but it reduces the consequences of inevitable human and process variability.

In conclusion, the enduring presence of Coppus steam turbines is not accidental. They fill a specific niche where steam is available, reliability is paramount, and simplicity outweighs the pursuit of maximum efficiency. Through energy recovery, mechanical drive, and auxiliary power applications, these turbines continue to deliver value in industrial environments. Their ongoing relevance reflects a design approach grounded in practicality rather than trends, and that approach remains just as important today as it was when the first Coppus turbines were built.

Coppus Steam Turbine Type for Your Process

Choosing the correct Coppus steam turbine type for a given process starts with understanding how the turbine will fit into the overall steam and mechanical system. Coppus turbines are not one-size-fits-all machines. They are built in several configurations, each intended to serve a particular operating role. The right choice depends less on theoretical efficiency and more on how the turbine will be used day after day in real plant conditions.

The first major distinction to consider is whether the turbine will be used primarily as a mechanical drive or for power generation. In many industrial plants, Coppus steam turbines are installed to drive pumps, compressors, fans, blowers, or mills directly. In these applications, shaft speed, torque characteristics, and load stability are the main concerns. For generator service, speed regulation and electrical stability become more important. Coppus offers turbine designs suited to both roles, but the internal configuration and control approach may differ.

One of the most common Coppus turbine types is the single-stage impulse turbine. This design is often selected for simple, robust mechanical drive applications where steam conditions are relatively high and the exhaust pressure can be matched to process needs. Single-stage turbines are compact, easy to maintain, and highly tolerant of variations in steam quality. They are well suited for driving centrifugal pumps or fans that operate at a constant speed and load.

For processes that require greater power output or improved efficiency over a wider operating range, multi-stage impulse turbines may be a better fit. These turbines extract energy from the steam across multiple rows of nozzles and blades, allowing more controlled expansion. While still mechanically straightforward, multi-stage units offer smoother torque delivery and better performance at partial load. This makes them suitable for compressors or larger mechanical drives with more demanding power requirements.

Another key choice is between back-pressure and condensing turbine configurations. A back-pressure Coppus steam turbine is selected when exhaust steam is needed for downstream process use. In this case, the turbine becomes part of the steam distribution system. The exhaust pressure is carefully controlled to meet heating, drying, or chemical process requirements. Back-pressure turbines are common in plants where steam serves multiple purposes and energy recovery is a priority.

Condensing Coppus turbines are chosen when maximum energy extraction from the steam is desired and there is no need for the exhaust steam in the process. These turbines exhaust into a condenser operating below atmospheric pressure. This increases the usable energy from the steam but adds complexity in the form of cooling water systems and condensate handling. Condensing turbines are more often used for generator applications or where steam availability exceeds process demand.

Another important factor is whether the process requires constant speed or variable speed operation. Many Coppus turbines are designed for constant-speed service, especially when driving generators or fixed-speed machinery. For applications where speed variation is required, such as certain pumping or milling processes, control systems must be selected carefully. While steam turbines are not as flexible as modern electric drives in speed variation, Coppus turbines can accommodate moderate speed control within defined limits.

Steam conditions play a critical role in turbine selection. Inlet pressure, temperature, and flow rate must match the turbine’s design envelope. Coppus turbines are available for a wide range of steam pressures, from moderate industrial levels to very high pressures. If the steam supply is variable or subject to interruptions, the turbine type should be chosen for stability rather than peak output. Conservative sizing is often preferred to ensure reliable operation under less-than-ideal conditions.

The nature of the driven process also influences turbine type. Processes with steady loads, such as circulation pumps or constant-flow compressors, are ideal candidates for simpler turbine designs. Processes with frequent load changes or intermittent operation may require more responsive governing systems and more robust mechanical margins. Understanding load behavior over time is just as important as knowing the maximum power requirement.

Installation constraints should not be overlooked. Available floor space, foundation strength, shaft alignment, and connection to existing equipment can all affect turbine selection. Coppus turbines are available in horizontal and vertical configurations, allowing them to be integrated into existing layouts. In retrofit projects, selecting a turbine type that minimizes structural and piping changes can significantly reduce installation cost and downtime.

Maintenance philosophy is another deciding factor. Plants with limited maintenance resources often prefer simpler turbine types with fewer stages and mechanical controls. Plants with strong maintenance programs may opt for more complex configurations if they offer operational advantages. Coppus turbines are generally forgiving, but matching the turbine type to the plant’s maintenance capability improves long-term reliability.

Finally, safety and regulatory requirements must be considered. Overspeed protection, pressure containment, and control systems must align with plant standards and local regulations. Some processes may require redundant protection or enhanced monitoring, influencing the choice of turbine type and accessories.

In summary, selecting the right Coppus steam turbine type for a process is a practical engineering decision rooted in how the turbine will actually be used. By considering the driven equipment, steam conditions, exhaust requirements, load behavior, installation constraints, and maintenance capability, plant engineers can choose a Coppus turbine that delivers reliable service over decades. The best choice is not the most advanced or efficient design, but the one that fits the process with the least compromise and the greatest long-term stability.

Beyond the basic turbine configuration, auxiliary systems play a major role in matching a Coppus steam turbine to a specific process. These supporting systems are often as important as the turbine itself, because they determine how smoothly and safely the machine operates over time. When selecting a turbine type, it is essential to consider how these systems will integrate with existing plant infrastructure.

The steam admission system is one such consideration. Coppus turbines can be equipped with different valve arrangements depending on control requirements. Simple hand valves may be sufficient for steady, noncritical applications, while automatically controlled throttle valves are preferred for processes that experience load changes. For more sensitive applications, a turbine with a well-matched governor and responsive control valve provides better speed stability and equipment protection.

Lubrication systems also influence turbine selection. Smaller Coppus turbines may use simple ring-oiled bearings, while larger units require forced lubrication systems with pumps, coolers, and filters. The choice depends on turbine size, speed, and duty cycle. In plants where maintenance attention is limited, simpler lubrication arrangements reduce the risk of failure due to pump or filter issues. In higher-power applications, more robust oil systems improve bearing life and reliability.

Another factor is exhaust handling. In back-pressure applications, the turbine exhaust must integrate smoothly into the downstream steam header. Poorly matched exhaust conditions can lead to unstable turbine operation or process disruptions. Selecting a turbine designed for the required exhaust pressure range helps avoid these problems. In condensing applications, the condenser capacity and vacuum stability must be compatible with the turbine’s exhaust characteristics.

Process continuity requirements may also dictate turbine selection. In continuous-process plants, unplanned downtime can be extremely costly. In these cases, a slightly oversized turbine operating well below its maximum rating may be preferred. This approach reduces mechanical stress and allows the turbine to handle temporary overloads without shutdown. Coppus turbines are well suited to this conservative sizing philosophy.

Environmental and operating conditions around the turbine should not be ignored. High ambient temperatures, dusty environments, or corrosive atmospheres can affect turbine performance and maintenance needs. Coppus turbines intended for such conditions may be specified with special materials, protective coatings, or enclosures. Selecting the right turbine type upfront avoids premature wear and frequent repairs.

Integration with plant control systems is another modern consideration. While Coppus turbines are traditionally mechanical machines, many installations now require electronic monitoring and control. Turbine types that can accept electronic governors, speed sensors, and remote shutdown signals are easier to integrate into distributed control systems. This is especially important in plants with centralized control rooms and strict safety protocols.

The startup and operating profile of the process also influences turbine choice. Processes that require frequent starts and stops may benefit from simpler turbine designs that tolerate thermal cycling. More complex turbines with tighter clearances may experience greater wear under such conditions. Understanding how often the turbine will be started, stopped, or idled helps guide the selection toward a suitable type.

Economic considerations inevitably come into play. The initial cost of the turbine, installation expense, operating efficiency, and maintenance cost must be weighed together. In many cases, the most economical choice over the turbine’s lifetime is not the lowest-cost unit upfront, but the one that offers stable operation and minimal downtime. Coppus turbines are often selected precisely because their long service life offsets modest efficiency losses.

It is also important to consider future process changes. Steam conditions, production rates, or equipment configurations may evolve over time. Selecting a turbine type with some operational flexibility allows the plant to adapt without replacing the turbine. Coppus turbines with generous design margins are particularly well suited to this approach.

In practical terms, selecting a Coppus steam turbine type is often an iterative process. Engineers evaluate process requirements, consult operating experience, and balance technical and economic factors. The final choice reflects not only calculated performance, but also confidence that the turbine will behave predictably in everyday operation.

Ultimately, the best Coppus steam turbine type for a process is one that disappears into the background of plant operations. It runs reliably, responds calmly to changes, and demands little attention beyond routine care. When properly selected and applied, a Coppus turbine becomes a stable, long-term asset rather than a source of ongoing concern.

Another layer in selecting the appropriate Coppus steam turbine type involves understanding how the turbine will interact with upstream and downstream process equipment. Steam systems in industrial plants are rarely isolated. They are interconnected networks where changes in one area can affect pressures, flows, and temperatures elsewhere. A turbine that is well matched to its immediate load but poorly matched to the broader steam system can create operational issues over time.

Upstream boiler characteristics are especially important. Boilers have limits on how quickly they can respond to changes in steam demand. If a turbine draws steam too aggressively during load increases, boiler pressure can drop and disrupt other processes. In such cases, a turbine type with smoother control characteristics and slower response may actually be preferable to a more aggressive design. Coppus turbines are often chosen for their stable, predictable steam consumption, which helps maintain system balance.

Downstream steam users also influence turbine selection. In back-pressure applications, the turbine must deliver exhaust steam at a pressure and quality that downstream equipment can accept. If downstream demand varies significantly, the turbine type and control system must accommodate those variations without causing excessive pressure swings. Some Coppus turbine configurations handle these conditions better due to their nozzle arrangement and governing style.

Mechanical coupling considerations are another practical factor. Direct-coupled turbines require precise speed matching and alignment with the driven equipment. In some processes, gearboxes or belt drives are used to match turbine speed to load requirements. The turbine type selected must be compatible with the chosen coupling method. Higher-speed turbines may require reduction gearing, while lower-speed designs can often be coupled directly, simplifying installation and maintenance.

Vibration tolerance is also relevant when selecting a turbine type. Some processes involve equipment that introduces cyclic loads or flow-induced vibration. A turbine with a heavier rotor and robust bearings may be better suited to such conditions. Coppus turbines are generally conservative in this regard, but specific models are better suited to high-inertia or pulsating loads than others.

Another consideration is steam availability during abnormal operating conditions. In some plants, steam pressure may drop during startup, shutdown, or upset conditions. A turbine that stalls or becomes unstable at reduced pressure can complicate recovery. Selecting a turbine type that can continue operating at reduced inlet pressure, even at lower output, improves overall process resilience.

The human factor also plays a role. Operators are more comfortable with equipment they understand. If a plant already has experience with a certain Coppus turbine type, choosing a similar configuration for a new process reduces training needs and operating risk. Familiar controls, startup procedures, and maintenance practices contribute to smoother long-term operation.

Documentation and standardization matter as well. Plants often develop internal standards for equipment selection. Coppus turbines that align with these standards are easier to approve, install, and support. Deviating from established turbine types should be justified by clear process benefits, not just marginal performance gains.

In facilities where safety margins are emphasized, turbine selection may intentionally favor lower operating speeds, thicker casings, and simpler control systems. These features reduce the consequences of component failure and make abnormal conditions easier to manage. Coppus turbines, with their traditionally conservative design, fit well into such safety-focused environments.

Over the life of the turbine, operational data becomes a valuable resource. Turbine types that provide clear, interpretable signals through pressure, temperature, and speed measurements help operators make informed decisions. Selecting a turbine configuration that supports straightforward monitoring improves both reliability and confidence in operation.

At a strategic level, selecting the right Coppus steam turbine type supports broader plant goals. Whether the objective is energy recovery, cost control, reliability, or operational simplicity, the turbine should reinforce that objective rather than work against it. A well-chosen turbine becomes part of the solution rather than a constraint.

In the end, Coppus steam turbine selection is less about finding an ideal theoretical match and more about choosing a practical, resilient machine that fits the realities of the process. By considering system interactions, operating behavior, human factors, and long-term plant strategy, engineers can select a turbine type that delivers steady value throughout its service life.

One final but often overlooked aspect of selecting a Coppus steam turbine type is how the turbine will age over time. No industrial process remains static for decades, yet Coppus turbines are commonly expected to operate for that long. A turbine that performs well when new but becomes difficult to operate as conditions drift is not a good long-term choice. This is why many plants favor turbine types that remain stable even as clearances open, controls wear, and steam conditions slowly change.

Wear patterns differ between turbine types. Simpler, single-stage impulse turbines tend to wear in predictable ways. Nozzle erosion, blade edge rounding, and seal leakage develop gradually and are easy to monitor. More complex, higher-performance designs may be more sensitive to wear and may show sharper drops in performance if maintenance is deferred. For plants where inspections are infrequent, this difference can be decisive.

Another long-term consideration is spare parts strategy. Turbine types that share components with other units in the plant reduce inventory and simplify logistics. Coppus turbines have historically emphasized commonality across models, but differences still exist between stages, shaft sizes, and casing designs. Selecting a turbine type that aligns with existing spare parts policies can reduce downtime when repairs are needed.

The availability of skilled support also matters. Even the most robust turbine requires occasional expert attention. Turbine types that are widely used and well understood are easier to support with in-house staff or local service providers. This practical reality often outweighs minor technical advantages offered by less common configurations.

From a lifecycle cost perspective, the chosen turbine type should minimize total ownership cost rather than just purchase price. This includes installation, fuel or steam opportunity cost, maintenance labor, spare parts, and the economic impact of downtime. Coppus turbines are often selected because their predictable behavior makes these costs easier to estimate and control.

Process safety reviews increasingly influence equipment selection. Turbine types that are easy to isolate, depressurize, and inspect fit better into modern safety management systems. Clear casing splits, accessible valves, and visible trip mechanisms reduce risk during maintenance. Coppus turbines traditionally score well in this area due to their straightforward layouts.

Another practical issue is noise and heat exposure in the turbine area. Some turbine types operate with higher exhaust velocities or casing temperatures, which can affect working conditions. Selecting a turbine configuration that minimizes these effects can improve operator comfort and reduce the need for additional shielding or insulation.

As plants modernize, digital monitoring and condition-based maintenance become more common. While Coppus turbines were not originally designed with digital systems in mind, many types adapt well to them. Turbine designs with accessible bearing housings and clear measurement points are easier to instrument with modern sensors. This adaptability extends the useful life of traditional turbine designs in modern operating environments.

It is also worth considering how the turbine will be perceived internally. Equipment that is known to be reliable tends to receive consistent care and attention. Turbine types that operators trust are more likely to be started correctly, monitored properly, and maintained on schedule. This human element reinforces the technical strengths of well-chosen Coppus turbines.

In practical terms, the “right” Coppus steam turbine type is often the one that causes the fewest discussions after installation. It does its job quietly, without frequent adjustments or surprises. Over time, it becomes part of the plant’s normal rhythm rather than a point of concern.

Ultimately, selecting a Coppus steam turbine type for your process is an exercise in realism. It requires accepting the limits of prediction and choosing a design that performs well not just under ideal conditions, but under the imperfect, changing conditions of real industrial operation. When that choice is made carefully, the turbine rewards the plant with decades of dependable service and steady performance.

Coppus Steam Turbines: Model Types for Industrial Reliability

Coppus steam turbines have earned a reputation for industrial reliability largely because of the way their model types are structured around practical operating needs rather than narrow performance targets. Each model family is designed to serve a specific range of pressures, speeds, and power outputs while maintaining a conservative mechanical design. This approach allows plants to select a turbine that fits their process with minimal compromise and predictable long-term behavior.

At the foundation of the Coppus product range are single-stage impulse turbine models. These are among the most widely installed Coppus turbines in industrial service. They are typically used for smaller to medium power applications where simplicity and durability are paramount. The single-stage design limits internal complexity, reduces the number of wear components, and makes inspection straightforward. For processes such as circulation pumps, cooling fans, or small compressors, these models provide dependable service with minimal attention.

For higher power requirements or applications where steam conditions are less favorable, Coppus offers multi-stage impulse turbine models. These models distribute the steam energy extraction across multiple stages, reducing blade loading and improving efficiency. From a reliability standpoint, this staged approach lowers mechanical stress and helps maintain stable operation across a broader load range. Multi-stage models are often chosen for larger compressors, process pumps, or generator drives where steady, continuous operation is expected.

Another important model distinction is based on exhaust configuration. Back-pressure turbine models are designed to deliver exhaust steam at a controlled pressure for downstream use. These models are common in plants that rely on steam for heating, drying, or chemical reactions. Reliability in this context means not only mechanical integrity, but also consistent exhaust pressure. Coppus back-pressure models are built with governing systems that emphasize smooth pressure control rather than aggressive load following, which supports stable plant operation.

Condensing turbine models represent another segment of the Coppus lineup. These models are used when maximum energy extraction from steam is required and when downstream steam use is limited or nonexistent. Condensing models operate with a condenser under vacuum conditions, allowing greater expansion of the steam. While this adds system complexity, Coppus condensing turbines retain the same conservative mechanical philosophy, prioritizing stable operation and long service life over peak efficiency.

Coppus also offers turbine models optimized for mechanical drive versus generator service. Mechanical drive models are configured to deliver high starting torque and stable shaft speed under load. These features are essential for equipment such as compressors and mills that impose significant inertia or resistance during startup. Generator-drive models, by contrast, emphasize precise speed regulation and compatibility with electrical control systems. Both model types are engineered with reliability as the primary objective.

Speed rating is another key differentiator among Coppus turbine models. Some models are designed for direct coupling to driven equipment at relatively low speeds, while others operate at higher speeds and require reduction gearing. Lower-speed models generally offer increased robustness and simpler maintenance, making them attractive in harsh industrial environments. Higher-speed models allow more compact designs and higher power density, but still maintain conservative stress levels compared to utility-scale turbines.

Coppus turbine models are also classified by their governing and control systems. Traditional mechanical governors are common in many installations and are valued for their simplicity and independence from electrical power. More recent models can accommodate hydraulic or electronic governors, improving speed control and integration with modern plant systems. Regardless of the control method, Coppus designs emphasize fail-safe behavior and predictable response to load changes.

From a reliability perspective, casing and rotor design are central to Coppus model differentiation. Casings are typically thick and rigid, providing structural stability and resistance to pressure and thermal distortion. Rotors are designed with generous safety margins and balanced to minimize vibration. These features reduce sensitivity to alignment issues, foundation movement, and thermal cycling, all of which are common in industrial environments.

Another factor contributing to reliability is the way Coppus turbine models handle off-design operation. Industrial processes rarely operate at a single steady point. Coppus turbines are designed to tolerate partial load operation, steam pressure fluctuations, and gradual changes in operating conditions without loss of stability. This tolerance is built into the model designs rather than added through complex controls.

Model selection also reflects maintenance philosophy. Some Coppus models are optimized for rapid inspection and servicing, with easy access to nozzles, blades, and bearings. These models are particularly valued in plants where maintenance windows are short and downtime is costly. The ability to inspect and repair a turbine quickly contributes directly to overall reliability.

In industrial practice, reliability is not defined by the absence of failures, but by the predictability of behavior and the ease of recovery when issues arise. Coppus steam turbine model types are designed with this definition in mind. When problems occur, they tend to develop slowly and provide clear warning signs, allowing planned intervention rather than emergency shutdown.

In summary, Coppus steam turbines achieve industrial reliability through thoughtful model differentiation rather than excessive complexity. By offering model types tailored to specific duties, steam conditions, and control needs, Coppus allows plants to choose turbines that align with real operating conditions. This alignment, combined with conservative mechanical design and practical controls, is the reason Coppus turbine models continue to be trusted in demanding industrial environments.

A deeper look at Coppus steam turbine model types also shows how reliability is reinforced through standardization and incremental variation rather than radical design changes. Over time, Coppus has refined its turbine families by adjusting dimensions, stage counts, and materials while keeping the basic architecture consistent. This evolutionary approach reduces unexpected behavior and allows operating experience from older units to carry forward into newer models.

One area where this consistency is especially valuable is in bearing and shaft design. Across many Coppus model types, bearing arrangements follow familiar patterns. Journal bearings are sized generously and placed to support stable rotor dynamics. Thrust bearings are designed to handle axial loads under both normal and upset conditions. Because these features are common across models, maintenance teams develop a strong understanding of how they behave, which improves diagnostic accuracy and response time.

Rotor construction also reflects a reliability-first philosophy. Coppus rotors are typically solid and relatively heavy compared to more efficiency-driven designs. While this increases inertia, it also smooths operation and dampens speed fluctuations. In mechanical drive applications, this inertia helps protect driven equipment from sudden torque changes. In generator applications, it contributes to stable frequency control.

Nozzle and blade arrangements differ between model types, but they share common design principles. Steam velocities are kept within conservative limits to reduce erosion and fatigue. Blade attachment methods emphasize mechanical security over ease of manufacture. These choices reduce the likelihood of blade failure, which is one of the most serious risks in any turbine installation.

Casing design varies by model type depending on pressure rating and exhaust configuration, but all Coppus casings are built to resist distortion and leakage. Split casings are common, allowing internal inspection without disturbing the foundation or major piping. This feature supports proactive maintenance, which is a key contributor to long-term reliability.

Another important reliability factor is how Coppus turbine models handle abnormal events. Overspeed protection systems are integral to all models, with mechanical trips that act independently of external power or control systems. This independence ensures that the turbine can protect itself even during plant-wide power failures or control system faults.

Thermal behavior is also carefully managed across model types. Clearances are designed to accommodate uneven heating during startup and shutdown. This reduces the risk of rotor rubs and casing distortion, which are common causes of damage in more tightly optimized machines. Coppus turbines tolerate slower or less precise startup procedures without serious consequences, which aligns with real-world operating practices.

Model differentiation also reflects the range of industries that use Coppus turbines. Some model types are tailored for continuous, steady-duty service typical of chemical and refining processes. Others are better suited to cyclic operation found in batch processing or auxiliary systems. By matching the model type to the duty cycle, plants can achieve higher effective reliability even if theoretical efficiency is not maximized.

Spare parts interchangeability is another advantage of the Coppus model strategy. Many internal components share dimensions or design features across multiple model types. This reduces the number of unique spares that must be stocked and shortens repair times when issues arise. In reliability-focused operations, this logistical simplicity is a major benefit.

The conservative rating of Coppus turbine models further supports dependable operation. Nameplate ratings typically include substantial safety margins, allowing the turbine to operate comfortably below its mechanical limits. This reduces wear rates and improves tolerance to occasional overloads or steam condition excursions.

In practice, the reliability of a Coppus turbine model is often measured by how rarely it becomes the limiting factor in plant operation. When selected correctly, these turbines run in the background, supporting the process without drawing attention. This low-profile performance is not accidental but is the result of deliberate model design choices focused on stability and longevity.

Ultimately, Coppus steam turbine model types represent a balance between standardization and customization. Each model family addresses a specific operating niche, while sharing common design principles that emphasize strength, simplicity, and predictability. This balance is what allows Coppus turbines to maintain their reputation for industrial reliability across decades of service and across a wide range of demanding applications.

Another way to understand Coppus steam turbine model types is to look at how they support long-term operational planning in industrial facilities. Reliability is not only about how a machine performs today, but also about how well it fits into maintenance schedules, upgrade paths, and plant life-cycle strategies. Coppus models are often selected because they simplify these broader planning efforts.

Many Coppus turbine model types are designed to be forgiving of alignment and foundation imperfections. In older plants, foundations may shift slightly over time, and piping loads may not be perfectly balanced. Turbine models with rigid casings and tolerant bearing arrangements are less sensitive to these realities. This reduces the frequency of alignment-related issues, which are a common source of chronic reliability problems in rotating equipment.

Another planning advantage is the predictable inspection interval associated with Coppus turbines. Because wear mechanisms develop slowly, inspection schedules can be set with confidence. Model types with easily accessible internals support visual inspection of nozzles, blades, and seals without major disassembly. This predictability allows maintenance activities to be aligned with planned outages rather than driven by unexpected failures.

Coppus turbine models also adapt well to partial modernization. Plants may choose to upgrade control systems, add monitoring, or improve lubrication without replacing the turbine itself. Model types with simple mechanical layouts and clear interfaces make these upgrades straightforward. This ability to evolve gradually supports long-term reliability by keeping the turbine compatible with changing plant standards.

The interaction between turbine model type and operating culture is another subtle but important factor. Some plants favor hands-on operation and local control, while others rely heavily on centralized automation. Coppus models can support both approaches. Turbine types with mechanical governors suit manual or semi-automatic operation, while models compatible with electronic control integrate smoothly into automated systems. Matching the model type to the plant’s operating culture reduces the risk of misuse or neglect.

Environmental exposure also influences model selection. Some Coppus turbine models are better suited to outdoor installation or harsh environments due to heavier casings, simplified sealing, and reduced reliance on sensitive electronics. In plants where environmental control is limited, these rugged models contribute directly to reliability by reducing vulnerability to heat, dust, or moisture.

Another reliability consideration is startup reliability after long idle periods. Some industrial turbines are only used during specific operating modes or seasonal demand. Coppus turbine models tend to restart reliably even after extended downtime, provided basic preservation practices are followed. This is partly due to their robust materials and conservative clearances, which reduce the risk of sticking or corrosion-related issues.

From a management perspective, Coppus turbine model types offer consistency across fleets of equipment. Plants with multiple turbines benefit from having similar operating procedures, spare parts, and training requirements. This consistency reduces complexity and the likelihood of errors, which is an often underappreciated contributor to reliability.

Documentation quality also plays a role. Coppus turbine models are typically supported by clear, practical documentation focused on operation and maintenance rather than abstract theory. This helps ensure that knowledge is retained even as personnel change over time. Reliable equipment is easier to keep reliable when the information needed to operate it correctly is accessible and understandable.

In long-running plants, equipment often becomes part of the institutional memory. Coppus turbine models that have proven themselves over decades earn a level of trust that influences future equipment choices. This trust is built on predictable behavior, manageable maintenance, and the absence of unpleasant surprises. Model types that deliver these qualities reinforce the perception of reliability year after year.

Ultimately, Coppus steam turbine model types are designed to support stability rather than optimization. They accept some efficiency trade-offs in exchange for mechanical strength, operational tolerance, and ease of care. In industrial environments where uptime matters more than theoretical performance, this trade-off is not a compromise but a deliberate and effective strategy.

For this reason, Coppus turbines continue to be specified in applications where reliability is non-negotiable. Their model types are not defined by complexity or novelty, but by how well they serve real processes over long periods. That focus on dependable service is what keeps Coppus steam turbines relevant in modern industry.

When examining Coppus steam turbine model types through the lens of industrial reliability, it becomes clear that their value lies as much in what they avoid as in what they include. Many modern machines chase higher efficiency through tighter tolerances, lighter components, and more complex control strategies. Coppus turbine models deliberately avoid pushing these limits, choosing instead to operate comfortably within proven mechanical boundaries.

This design restraint is reflected in how different model types handle thermal stress. Steam turbines experience repeated heating and cooling cycles, especially in plants with variable operating schedules. Coppus models are designed with generous clearances and robust casing structures that accommodate uneven thermal expansion. This reduces the likelihood of casing distortion or rotor rubs, which can quickly escalate into major failures.

Another area where model design supports reliability is in the treatment of steam quality. Industrial steam is rarely ideal. It may contain moisture, trace chemicals, or small particulates. Coppus turbine models are tolerant of these conditions because their blade profiles, materials, and steam velocities are chosen to resist erosion and corrosion. While clean, dry steam is always preferable, these turbines continue to operate acceptably even when steam quality is less than perfect.

Model-specific differences also address varying duty cycles. Some Coppus turbines are intended for continuous base-load operation, while others are better suited to intermittent or standby service. Base-load models emphasize steady-state stability and long wear life. Standby-oriented models focus on reliable starts and rapid availability. Selecting the correct model type for the duty cycle reduces stress on the turbine and improves overall reliability.

Another contributor to dependable operation is the straightforward fault behavior of Coppus turbine models. When problems arise, they tend to manifest as gradual changes in performance rather than sudden failures. Increased vibration, rising bearing temperatures, or reduced output typically provide ample warning. This predictability allows maintenance teams to intervene before damage becomes severe.

Coppus turbine model types also support reliability through clear separation of functions. Steam admission, speed control, lubrication, and protection systems are typically distinct and accessible. This modularity makes troubleshooting easier and reduces the risk that a single fault will cascade into a major outage.

The physical layout of many Coppus models reflects an emphasis on maintainability. Components that require periodic attention are accessible without extensive disassembly. This encourages routine inspection and preventive maintenance, which directly supports long-term reliability. Equipment that is difficult to access is often neglected, regardless of its theoretical durability.

Another practical benefit of Coppus turbine models is their compatibility with conservative operating practices. Many industrial plants prefer to run equipment below maximum ratings to extend service life. Coppus turbines are well suited to this approach because their performance remains stable at reduced loads. They do not rely on operating near design limits to remain efficient or stable.

Over decades of service, many Coppus turbine models have demonstrated the ability to survive changes in process conditions that were never anticipated at the time of installation. Increases or decreases in steam pressure, changes in exhaust requirements, or shifts in load can often be accommodated within the turbine’s design envelope. This flexibility reduces the need for costly replacements when processes evolve.

The reliability of Coppus steam turbine models is also reinforced by institutional knowledge. Because these turbines have been used for so long, best practices for their operation and maintenance are well established. This accumulated experience reduces the learning curve for new installations and helps prevent avoidable mistakes.

In the end, Coppus steam turbine model types represent a mature technology refined by decades of industrial use. Their reliability does not come from cutting-edge features, but from thoughtful design choices that prioritize durability, tolerance, and simplicity. In environments where steady operation matters more than peak performance, these qualities remain invaluable.

That is why Coppus turbines continue to be selected for critical industrial roles. Their model types are shaped by real-world experience, and that experience has consistently shown that conservative design, when applied intelligently, is one of the strongest foundations for industrial reliability.

A Guide to Coppus Steam Turbine Types and Capabilities

Coppus steam turbines are designed to meet the practical demands of industrial environments where reliability, longevity, and predictable performance matter more than peak efficiency. Rather than offering highly specialized machines for narrow operating points, Coppus has developed turbine types that cover broad ranges of steam conditions and duties. This guide explains the main Coppus steam turbine types and the capabilities that define their use in real industrial processes.

Core Design Philosophy

All Coppus steam turbine types share a common design philosophy. They are impulse turbines built with conservative stress levels, robust casings, and simple internal arrangements. The goal is stable, long-term operation under variable conditions. Clearances are generous, materials are selected for durability, and controls are designed to fail safely. This philosophy underpins every turbine type in the Coppus lineup.

Single-Stage Impulse Turbines

Single-stage Coppus turbines are among the simplest and most widely used types. Steam expands through a single set of nozzles and transfers energy to one row of moving blades. These turbines are compact, easy to maintain, and tolerant of changes in steam quality and pressure.

Their capabilities include reliable operation in small to medium power ranges and excellent suitability for mechanical drives such as pumps, fans, and blowers. They are especially effective where steam pressure is relatively high and exhaust pressure requirements are moderate. Because of their simplicity, they are often chosen for applications where maintenance resources are limited or where uptime is critical.

Multi-Stage Impulse Turbines

Multi-stage Coppus turbines extract energy from steam across multiple stages, allowing smoother expansion and improved efficiency over a wider operating range. While still mechanically straightforward, these turbines are capable of higher power outputs and more stable performance at partial load.

These turbines are commonly used for larger mechanical drives and generator applications. Their capabilities include better torque control, reduced blade loading, and improved tolerance of fluctuating loads. They are well suited to compressors and other equipment that demand steady power delivery over long operating periods.

Back-Pressure Turbines

Back-pressure Coppus turbines are designed to exhaust steam at a controlled pressure for downstream process use. Rather than maximizing energy extraction, their primary capability is balancing power generation or mechanical drive with process steam requirements.

These turbines are widely used in plants where steam serves multiple purposes, such as heating, drying, or chemical processing. Their strength lies in stable exhaust pressure control and predictable steam flow. This makes them ideal for energy recovery applications where steam pressure would otherwise be reduced by throttling.

Condensing Turbines

Condensing Coppus turbines are used when the goal is to extract as much energy as possible from the steam. These turbines exhaust into a condenser operating under vacuum, allowing greater expansion of the steam.

Their capabilities include higher power output from a given steam flow and suitability for generator service or standalone power generation. While condensing systems add complexity, Coppus condensing turbines retain the same conservative mechanical design and operational stability found in other types.

Mechanical Drive Turbines

Coppus mechanical drive turbines are optimized to deliver torque directly to driven equipment. They are designed to handle high starting loads and maintain stable speed under varying mechanical resistance.

Their capabilities include direct coupling to pumps, compressors, mills, and blowers, as well as compatibility with gearboxes where speed matching is required. These turbines are valued for their smooth torque delivery and resistance to load-induced vibration.

Generator Drive Turbines

Generator drive turbine types focus on speed accuracy and stability. Maintaining consistent rotational speed is critical for electrical output quality, and Coppus generator turbines are equipped with appropriate governing systems to meet this requirement.

Their capabilities include reliable operation at constant speed, compatibility with both mechanical and electronic governors, and integration into plant electrical systems. They are often used in combined heat and power installations.

Speed and Size Ranges

Coppus turbines are available across a wide range of speeds and power ratings. Lower-speed turbines emphasize mechanical robustness and simplicity, while higher-speed turbines offer greater power density. Across all ranges, ratings are conservative, allowing turbines to operate well below their mechanical limits for most of their service life.

Control and Protection Systems

Coppus turbine types can be equipped with various control systems depending on application needs. Mechanical governors provide simplicity and independence from electrical power. Hydraulic and electronic systems offer tighter control and easier integration with modern plant controls. Overspeed protection is standard across all turbine types.

Operational Capabilities

Across all types, Coppus steam turbines are capable of handling variable steam conditions, partial-load operation, and gradual process changes. They are designed to start reliably, run smoothly, and provide clear warning signs when maintenance is needed. This predictability is a key part of their industrial value.

Conclusion

Coppus steam turbine types are defined by what they reliably deliver rather than by extreme performance metrics. By offering single-stage, multi-stage, back-pressure, condensing, mechanical drive, and generator-focused designs, Coppus covers the full range of common industrial steam turbine applications. Their capabilities align with real-world operating conditions, making them a trusted choice for facilities where long-term reliability and operational stability are essential.

Application Matching and Capability Trade-Offs

Understanding Coppus steam turbine types also requires recognizing the trade-offs that come with each capability. Coppus turbines are intentionally balanced machines. Gains in efficiency, power density, or control precision are never pursued at the expense of stability or durability. This makes application matching a practical exercise rather than a theoretical one.

Single-stage turbines, for example, trade efficiency for ruggedness and ease of care. Their capability lies in dependable mechanical output with minimal internal wear points. Multi-stage turbines, while more efficient, still preserve wide operating margins and resist instability at partial load. Knowing which capability matters most in a given process helps ensure long-term success.

Steam Condition Capability

One of the strongest capabilities shared across Coppus turbine types is tolerance to real-world steam conditions. Many industrial steam supplies experience moisture carryover, pressure swings, or chemical contamination. Coppus turbines are designed to survive these conditions without rapid degradation. Blade geometry, materials, and steam velocities are chosen to minimize erosion and corrosion rather than to chase theoretical efficiency limits.

This capability is particularly important in older plants or in facilities that recover steam from waste heat sources. Coppus turbines continue to perform predictably where more sensitive machines might suffer accelerated wear or frequent trips.

Load Behavior and Process Stability

Different Coppus turbine types handle load behavior in distinct ways. Mechanical drive turbines are built to absorb load fluctuations without transmitting shock to the driven equipment. Generator turbines emphasize speed stability and smooth response to electrical load changes. Back-pressure turbines prioritize exhaust pressure consistency, sometimes accepting slower response in shaft power to protect downstream processes.

These differences highlight a key Coppus capability: prioritizing process stability over aggressive control. In most industrial settings, stable operation reduces overall risk and improves plant uptime.

Startup, Shutdown, and Cycling Capability

Coppus steam turbines are well known for their forgiving behavior during startup and shutdown. Clearances and materials are selected to handle uneven heating and cooling. This capability is especially valuable in plants with frequent cycling or irregular operating schedules.

Turbine types intended for standby or auxiliary service emphasize reliable starting after long idle periods. Base-load turbine types emphasize thermal stability during continuous operation. Selecting the correct type ensures that the turbine’s strengths align with how it will actually be used.

Maintenance and Inspection Capability

Another defining capability of Coppus turbine types is maintainability. Many models allow inspection of critical components without removing the turbine from service piping or disturbing alignment. Bearings, seals, and governing components are accessible and familiar to maintenance personnel.

This capability directly supports reliability. Equipment that can be inspected easily is more likely to be inspected regularly. Coppus turbines are designed with this reality in mind.

Integration Capability

Modern industrial plants increasingly rely on centralized control and monitoring systems. Coppus turbine types can be equipped with mechanical, hydraulic, or electronic governors depending on integration needs. While the turbine itself remains mechanically straightforward, its capability to interface with modern systems allows it to remain relevant in updated facilities.

This adaptability supports gradual modernization without forcing wholesale replacement of proven equipment.

Longevity as a Capability

Perhaps the most defining capability of Coppus steam turbines is longevity. Many units operate reliably for several decades with only routine maintenance. This is not incidental. It is the result of conservative design, moderate operating stresses, and predictable wear patterns.

Longevity reduces lifecycle cost, simplifies planning, and increases confidence in plant operations. In industrial environments where unexpected failures are unacceptable, this capability often outweighs all others.

Selecting for Capability, Not Specification

A common mistake in turbine selection is focusing too heavily on nameplate specifications. Coppus turbine types are best selected based on capability under real conditions rather than peak performance numbers. How the turbine behaves during upset conditions, partial load, or imperfect steam quality matters more than maximum efficiency at design point.

Final Perspective

Coppus steam turbine types and capabilities reflect decades of industrial experience. They are machines designed to work with processes rather than against them. By understanding what each turbine type is capable of, and just as importantly what it is designed to avoid, engineers can select equipment that supports stable, reliable operation over the long term.

Another important capability of Coppus steam turbines is how well they handle imperfect operating discipline. In real industrial environments, procedures are not always followed perfectly. Startup rates vary, valves may be adjusted manually, and operating conditions can drift. Coppus turbine types are designed with enough tolerance to absorb these variations without immediate damage. This does not eliminate the need for proper operation, but it reduces the risk that minor deviations will lead to serious failures.

Coppus turbines also demonstrate strong capability in mixed-duty roles. In some plants, a single turbine may alternate between driving equipment, supporting process steam needs, and generating power depending on operating mode. While not optimized for every scenario, many Coppus turbine types can accommodate these shifts within reasonable limits. This flexibility is especially valuable in facilities with changing production demands.

Another area where Coppus turbines perform well is mechanical robustness under long-term vibration exposure. Industrial plants often contain multiple rotating machines, piping systems, and structural elements that introduce background vibration. Coppus turbine designs, with their heavy casings and stable rotor dynamics, are less sensitive to these influences. Over time, this reduces fatigue-related issues and contributes to extended service life.

The simplicity of Coppus turbine internals also supports reliable troubleshooting. When problems arise, the cause is usually mechanical and visible. Worn bearings, eroded nozzles, or sticking valves can be identified through inspection rather than complex diagnostics. This clarity speeds up repair and reduces dependence on specialized expertise.

Coppus steam turbines are also capable of operating effectively in plants with limited utilities. Some turbine types rely minimally on external electrical power, using mechanical governors and self-contained lubrication systems. In remote or older facilities, this independence improves reliability by reducing dependence on support systems that may themselves be unreliable.

Another practical capability is tolerance to steam supply interruptions. In processes where steam flow may be reduced or temporarily lost, Coppus turbines generally coast down smoothly and restart without difficulty once steam is restored. Clearances and materials are selected to prevent damage during these transitions.

Coppus turbine types also support conservative operating strategies. Many plants choose to operate turbines well below rated output to maximize life. Coppus turbines maintain stable performance and good control under these conditions, rather than becoming unstable or inefficient at reduced load.

From a training standpoint, Coppus turbines are approachable machines. Operators can learn their behavior through experience and observation. This capability supports knowledge transfer within organizations and reduces the risk associated with personnel changes.

Another long-term benefit is adaptability to regulatory and safety updates. As safety standards evolve, Coppus turbine types can often be upgraded with additional instrumentation, interlocks, or protective devices without major redesign. This adaptability allows plants to maintain compliance while retaining proven equipment.

Over decades of service, many Coppus turbines become reference points within plants. Their steady behavior sets expectations for how rotating equipment should perform. This cultural impact reinforces reliability by promoting careful operation and maintenance practices across the facility.

In practical terms, the capabilities of Coppus steam turbine types are best measured by their absence of drama. They do not demand constant attention, do not surprise operators, and do not force frequent redesign of surrounding systems. They operate steadily, respond predictably, and wear slowly.

That combination of tolerance, simplicity, and durability defines the real capability of Coppus steam turbines. It is why they continue to be specified in demanding industrial roles and why, once installed, they are often left in place for generations of plant operation.

Another capability that distinguishes Coppus steam turbines is their predictable end-of-life behavior. Unlike highly optimized machines that can fail abruptly once clearances or materials degrade beyond narrow limits, Coppus turbine types tend to decline gradually. Output may reduce slightly, steam consumption may increase, or vibration levels may rise, but these changes usually occur over long periods. This gives operators time to plan refurbishment or replacement without emergency shutdowns.

Refurbishment capability is an important part of the Coppus value proposition. Many turbine types can be overhauled multiple times during their service life. Casings, shafts, and major structural components often remain usable after decades of operation. Refurbishment typically focuses on wear parts such as bearings, seals, nozzles, and blades. This approach extends service life and spreads capital cost over a much longer period than equipment designed for short replacement cycles.

Another strength is compatibility with incremental efficiency improvements. While Coppus turbines are not designed for maximum efficiency, some model types allow for updated nozzle designs, improved sealing, or upgraded governors during overhaul. These changes can modestly improve performance without compromising reliability. This incremental improvement capability aligns well with plants that prefer gradual optimization rather than disruptive upgrades.

Coppus turbines also show strong capability in handling asymmetric or off-axis loads. In real installations, perfect alignment is rare. Thermal growth, piping forces, and foundation movement introduce stresses that some machines cannot tolerate. Coppus turbine designs allow for a degree of misalignment and uneven loading without rapid bearing or seal failure. This tolerance reduces maintenance intervention and extends operating intervals.

Another often overlooked capability is acoustic stability. Coppus turbines generally operate with steady, consistent sound profiles. Sudden changes in noise often correlate clearly with developing issues, making auditory monitoring a useful diagnostic tool. Operators familiar with these machines can detect problems early simply by listening, an advantage rarely possible with more complex or enclosed systems.

In facilities where redundancy is limited, restart reliability becomes critical. Coppus turbine types are known for their ability to return to service after trips or shutdowns with minimal adjustment. Governors reset predictably, lubrication systems reestablish oil flow quickly, and rotors accelerate smoothly. This behavior supports rapid recovery from process upsets.

Coppus steam turbines also perform well in aging plants where documentation may be incomplete or original design assumptions are no longer fully known. Their forgiving nature allows them to continue operating safely even when precise historical data is unavailable. This capability is especially valuable in legacy industrial facilities.

Another factor is interoperability with other energy systems. Coppus turbines integrate well with boilers, pressure-reducing stations, and heat recovery systems. Their predictable steam demand and exhaust characteristics make system-level behavior easier to manage. This reduces control conflicts and improves overall plant stability.

Over time, Coppus turbine types often become benchmarks for acceptable operating behavior. Newer equipment is compared against them, and operating standards are shaped around their performance. This influence reinforces their role as reliability anchors within industrial systems.

Ultimately, the capability of Coppus steam turbine types lies in their alignment with industrial reality. They are designed not for ideal conditions, but for the imperfect, evolving, and sometimes unpredictable environments in which they operate. Their steady decline patterns, rebuildability, tolerance to misalignment, and calm response to disturbances make them uniquely suited to long-term industrial service.

That is why Coppus turbines are rarely described as impressive machines, yet are frequently described as indispensable ones.

Coppus Steam Turbine Options for Steam-Driven Equipment

Coppus steam turbines offer a range of practical options for driving equipment directly with steam in industrial environments. These turbines are chosen not for novelty or extreme performance, but for how reliably they convert available steam into steady mechanical motion. When steam is already part of the process, Coppus turbines provide a straightforward way to power rotating equipment while maintaining control, durability, and long service life.

One of the most common Coppus options for steam-driven equipment is the single-stage impulse turbine. This option is well suited for driving pumps, fans, and blowers that operate at relatively constant speed and load. The single-stage design keeps internal parts to a minimum, which reduces wear and simplifies maintenance. For equipment that runs continuously and does not demand tight speed regulation, this option provides dependable performance with minimal attention.