Power Machines – Generators, Steam Engines and Steam Turbines, Electric, and Vibration Motors, Pumps

EMS, which began in a small factory of electric motors, vibration motors, diesel generators, and steam turbines has become a leading global supplier of electronic products for different segments. The search for excellence has resulted in the diversification of the business, adding to the electric motors products which provide from power generation to more efficient means of use.

EMS Power Machines

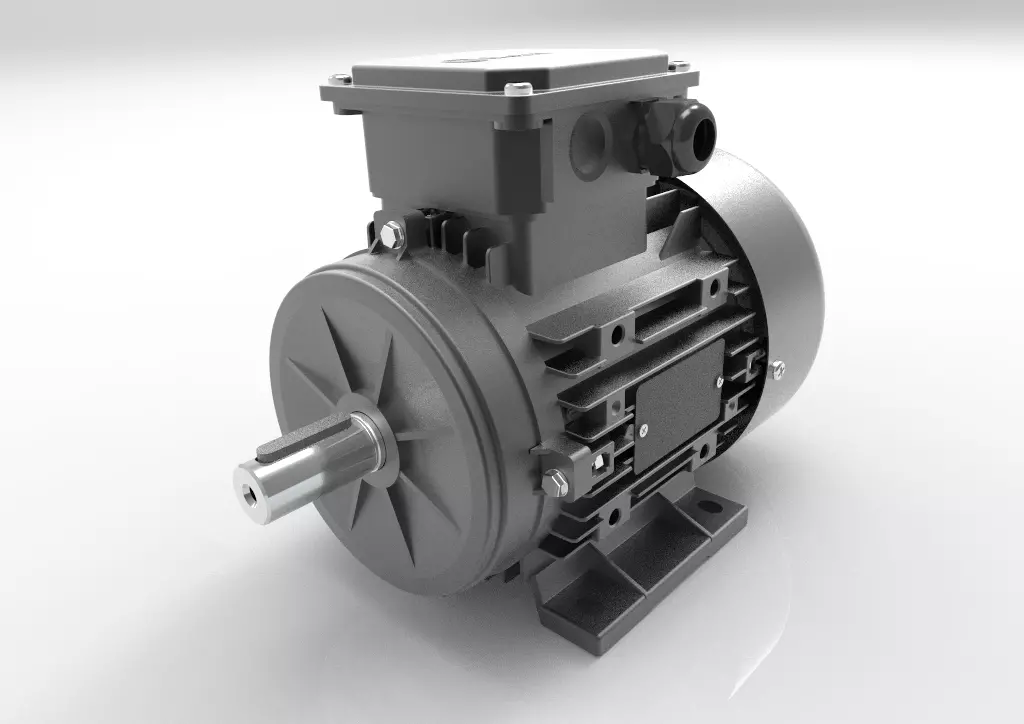

This diversification has been a solid foundation for the growth of the company which, for offering more complete solutions, currently serves its customers in a dedicated manner. Even after more than 50 years of history and continued growth, electric motors remain one of EMS’s main products. Aligned with the market, EMS develops its portfolio of products always thinking about the special features of each application.

To provide the basis for the success of EMS Motors, this simple and objective guide was created to help those who buy, sell, and work with such equipment. It brings important information for the operation of various types of motors.

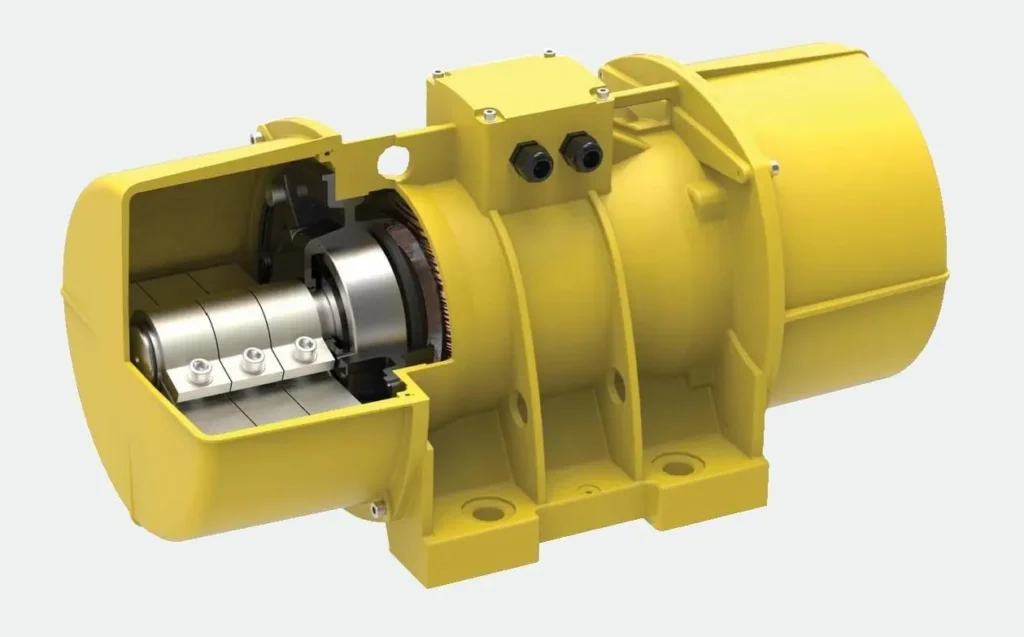

As a manufacturer, we design and manufacture diesel generators, small-size steam turbines and marine steam engines, vibration motors, and AC & DC Electric motors.

Diesel Generators as Power Machines

A diesel generator is a generator that is powered by a diesel engine. Diesel generators are used in a variety of applications, including:

- Backup power: Diesel generators are often used as backup power sources in case of a power outage. They are also used in remote areas where there is no access to the electrical grid.

- Primary power: Diesel generators can also be used as primary power sources in areas where there is no access to the electrical grid, such as construction sites and mining camps.

- Mobile power: Diesel generators can be mounted on trailers or trucks, making them ideal for mobile power applications, such as disaster relief and emergency response.

Diesel generators are available in a variety of sizes, from small portable generators that can power a few appliances to large industrial generators that can power entire buildings.

Diesel generators are a reliable and efficient source of power. They are also relatively easy to maintain.

Here are some of the benefits of using diesel generators:

- Reliability: Diesel generators are very reliable machines. They can operate for long periods of time without any problems.

- Efficiency: Diesel generators are very efficient machines. They can convert a high percentage of the fuel’s energy into electricity.

- Durability: Diesel generators are very durable machines. They can withstand harsh operating conditions.

- Versatility: Diesel generators can be used in a variety of applications, from backup power to primary power to mobile power.

Diesel generators are an essential tool for many businesses and organizations. They provide a reliable and efficient source of power in a variety of situations.

Here are some examples of diesel generator applications:

- Hospitals: Hospitals use diesel generators as backup power sources in case of a power outage. This ensures that critical medical equipment can continue to operate.

- Data centers: Data centers use diesel generators as backup power sources to protect sensitive data.

- Construction sites: Construction sites use diesel generators to provide power for tools and equipment.

- Mining camps: Mining camps use diesel generators to provide power for lights, heating, and other equipment.

- Emergency response: Emergency response teams use diesel generators to provide power for lighting, communication equipment, and other life-saving equipment.

Diesel generators play an important role in our society. They provide a reliable and efficient source of power in a variety of situations.

We manufacture diesel generators starting from 15 kVa up to 2250 Kva with the following engine options:

- Perkins Engines

- Cummins Engines

- Ricardo Engines

- Baudoin Engines

- Shanghai Dongfeng Engines

- Volvo Engines

- Yangdong Engines

Diesel generators are a type of backup power supply that uses a diesel engine to generate electricity. They are commonly used in industrial and commercial settings, as well as in residential areas where power outages are common.

Diesel generators work by converting diesel fuel into mechanical energy through an engine. The engine then turns an alternator to produce electrical power. The amount of electricity produced by the generator depends on the size and capacity of the engine and alternator.

There are several advantages to using diesel generators. First, diesel fuel is more efficient than gasoline and can produce more power per unit of fuel. This makes diesel generators more cost-effective in the long run. Second, diesel generators are more reliable than other types of generators and require less maintenance. Finally, diesel generators are more durable and can operate for longer periods of time than other types of generators.

Diesel generators come in a variety of sizes and capacities to meet different power needs. Small diesel generators can produce enough power to run a single appliance or a small home, while larger diesel generators can power entire buildings or industrial complexes. Some diesel generators are portable and can be easily transported to different locations.

When selecting a diesel generator, it is important to consider several factors. The first is the power capacity of the generator. This should be based on the amount of power needed to run the desired appliances or equipment. The second factor is the run time of the generator. This will determine how long the generator can operate without needing to be refueled. The third factor is the noise level of the generator. Diesel generators can be noisy, so it is important to select one that is appropriate for the location where it will be used.

In addition to providing backup power, diesel generators are also used in remote areas where access to electricity is limited or unavailable. They are commonly used in construction sites, mining operations, and other industrial settings where electricity is needed but not readily available.

Overall, diesel generators are an efficient, reliable, and cost-effective backup power supply that can be used in a variety of settings. With proper maintenance and care, they can provide years of reliable service and peace of mind during power outages and other emergencies.

Engine

- Ricardo, Cummins, Perkins, Baudoin, Shanghai Dongfeng, Volvo or Yangdong heavy-duty diesel engine

- 12V / 24V starter and charge alternator

- Replaceable air, fuel, and oil filters

- Mechanical governor control

- Tropical type radiator

- Flexible fuel hose

- Oil drain valve and extension hose

- Industrial-type silencer and steel compensator

- Maintenance-free starter battery

- Water jacket heater

- 1500 rpm engine speed

Alternator

- IP 21-23 Protection Standard

- H Insulation Class

- 50 Hz Frequency

- 4 pole brushless synchronous type alternator

- Automatic Voltage Regulator (AVR)

- 400/230V AC Output Voltage – 1500 rpm

Soundproof Chassis and Canopy

- Convenient design for easy lifting and carrying

- High-standard soundproof canopy design

- Modular design with quickly removable nuts – bolts

- Lockable doors

- Transparent window for watching Control Panel

- Electrostatic powder painted, providing protection

against harsh weather conditions - Emergency STOP button

- Fuel tank inside the chassis

- Anti-vibration wedges (engine – chassis and chassis –

ground)

Optional

- Thermal magnetic CB (for automatic models)

- Super Silent Canopy

- Mobile Generator Sets

- Automatic fuel filling system

- Synchronization panel

- 3 Pole and 4 Pole ATS (Automatic Transfer Switch)

- Fuel Heater, Oil Heater

- External fuel tank and automatic fuel filling system

- Fuel-water separator filter

- Remote monitoring and control system

Generators are delivered to our customers as ready for operation, motor oil and antifreeze coolant are filled, and the battery is charged. After the generator exhaust system and electrical connections are made under the supervision of authorized service, it can be operated immediately after refueling. All information about your generator is declared on the product label as in the following example. The product label is located on the automatic control panel of opening the generator or the soundproof canopy of the canopied generator.

Steam Engines

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be transformed, by a connecting rod and crank, into rotational force for work.

Steam engines were first developed in the United Kingdom during the early 19th century and used for railway transport until the middle of the 20th century. They were also used in a wide variety of other applications, such as powering factories, ships, and sawmills.

Steam engines are external combustion engines, which means that the working fluid is separated from the combustion products. The ideal thermodynamic cycle used to analyze this process is called the Rankine cycle.

There are two main types of steam engines: reciprocating steam engines and rotary steam engines.

Reciprocating steam engines are the most common type of steam engine. They work by using a piston to move back and forth inside a cylinder. The steam pressure pushes the piston back and forth, which turns a crankshaft.

Rotary steam engines work by using a rotating rotor to move steam around a chamber. The steam pressure pushes the rotor around, which turns a crankshaft.

Steam engines are a versatile and powerful type of engine that has been used for a wide variety of applications over the centuries. While they are no longer as common as they once were, they are still used in some applications today, such as in power plants and steam locomotives.

Here are some examples of steam engines:

- Steam locomotives: Steam locomotives were used to power trains for over a century. They are still used in some parts of the world today.

- Steam turbines: Steam turbines are used to generate electricity in power plants. They are also used to power some ships and submarines.

- Beam engines: Beam engines were used to power factories in the 19th century. They are no longer commonly used, but some examples can still be seen in museums.

- Rotary steam engines: Rotary steam engines are not as common as reciprocating steam engines, but they are still used in some applications, such as in power plants and steam cars.

Steam engines are a fascinating and important part of technological history. They helped to power the Industrial Revolution and have played a vital role in the development of modern society.

A steam engine is a machine that converts thermal energy of steam into mechanical energy. Steam engines were used for a wide variety of purposes during the Industrial Revolution, including powering factories, locomotives, and ships.

Steam engines work by using the pressure of steam to push a piston up and down in a cylinder. The piston is connected to a crankshaft, which turns as the piston moves. The crankshaft can then be used to power other machines, such as a generator or a locomotive wheel.

There are two main types of steam engines: atmospheric steam engines and high-pressure steam engines.

Atmospheric steam engines were the first type of steam engine to be developed. They worked by using the pressure of the atmosphere to push a piston down in a cylinder. The piston was then pulled back up in the cylinder by the steam pressure. Atmospheric steam engines were relatively inefficient, and they were eventually replaced by high-pressure steam engines.

High-pressure steam engines were more efficient than atmospheric steam engines because they used the pressure of the steam to push the piston both up and down in the cylinder. High-pressure steam engines were also more powerful than atmospheric steam engines, and they were able to power a wider variety of machines.

Steam engines played a vital role in the Industrial Revolution. They helped to power factories, locomotives, and ships, which made it possible to mass-produce goods and transport them long distances. Steam engines also helped to improve the lives of people by providing a more reliable source of power for lighting and heating.

Here are some of the benefits of using steam engines:

- Efficiency: Steam engines are very efficient machines. They can convert a high percentage of the fuel’s energy into mechanical energy.

- Reliability: Steam engines are very reliable machines. They can operate for long periods of time without any problems.

- Durability: Steam engines are very durable machines. They can withstand harsh operating conditions.

- Versatility: Steam engines can be used in a variety of applications, from powering factories to locomotives to ships.

Steam engines are no longer widely used, but they played a vital role in the development of modern technology. They helped to power the Industrial Revolution and made it possible for us to enjoy the many benefits of modern life.

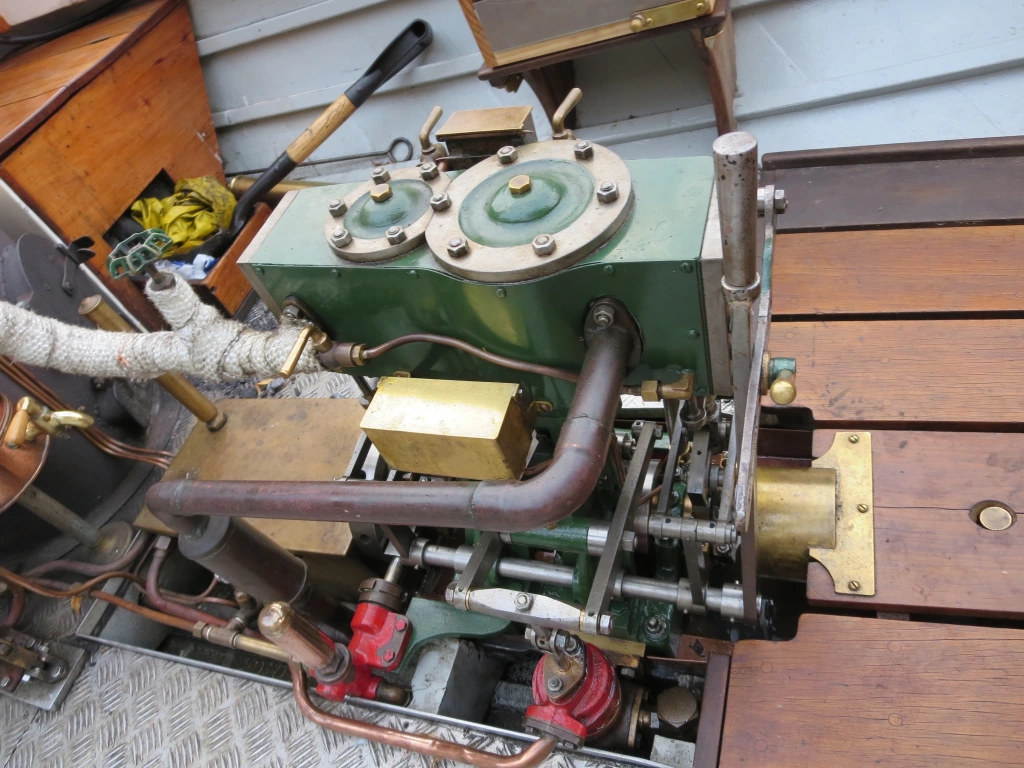

We manufacture steam launch engines for marine purposes, for wooden boats and other marine vessels

Steam engines for small boats are an excellent option for those who want to power their watercraft using an eco-friendly and reliable source of energy. These engines use steam generated from heating water with an external source, such as wood, coal, or oil, to produce mechanical energy that drives a boat’s propeller. While steam engines have been around for more than 200 years, they continue to be a popular choice for powering small boats today.

Steam engines come in different sizes and configurations, making it possible to find the right one for your small boat. Generally, a steam engine for a small boat can range from 5 to 20 horsepower, with some models producing up to 100 horsepower. The size of the engine you need will depend on the size and weight of your boat, as well as how much speed you want to achieve.

Steam Engine Application Areas

Steam engines were used in a wide variety of applications during the Industrial Revolution and beyond. Here are some examples:

- Transportation: Steam engines were used to power trains, ships, and steamboats. They were also used to power streetcars and early automobiles.

- Manufacturing: Steam engines were used to power a wide variety of machinery in factories, including textile mills, sawmills, and metalworking shops.

- Mining: Steam engines were used to power pumps and other machinery in mines.

- Agriculture: Steam engines were used to power threshing machines, cotton gins, and other agricultural machinery.

- Power generation: Steam engines were used to generate electricity in power plants.

Steam engines are still used in some applications today, such as in power plants, steam locomotives, and steam turbines. However, they have largely been replaced by other types of engines, such as internal combustion engines and electric motors.

Here are some specific examples of how steam engines were used in different applications:

- Steam locomotives: Steam locomotives were used to transport people and goods on railways. They were the primary mode of rail transportation for over a century.

- Steam turbines: Steam turbines are used to generate electricity in power plants. They are also used to power some ships and submarines.

- Beam engines: Beam engines were used to power factories in the 19th century. They were typically used to drive large machines, such as textile mills and sawmills.

- Rotary steam engines: Rotary steam engines are not as common as reciprocating steam engines, but they are still used in some applications, such as in power plants and steam cars.

Steam engines played a vital role in the development of modern society. They helped to power the Industrial Revolution and made possible the transportation of goods and people over long distances.

The Evolution and Mechanics of Steam Engines

Steam engines represent one of humanity’s most transformative inventions, driving the Industrial Revolution and shaping the modern world. At their core, steam engines convert thermal energy from steam into mechanical work, a process that harnesses the power of expanding gas to move pistons or turbines. While their prominence has waned with the rise of internal combustion engines and electric motors, they remain a fascinating technology with niche applications today, as exemplified by manufacturers like EMS Power Machines.

Historical Context

The steam engine’s story begins in the late 17th century with rudimentary designs like Thomas Savery’s 1698 “Miner’s Friend,” a steam-powered pump used to remove water from mines. However, it was Thomas Newcomen’s atmospheric engine in 1712 that marked the first practical steam engine, using steam to create a vacuum that drove a piston. The real breakthrough came with James Watt, whose improvements in the 1760s—most notably the separate condenser—vastly increased efficiency. Watt’s engine didn’t just pump water; it powered factories, mills, and eventually locomotives and ships, ushering in an era of mechanized industry.

By the 19th century, steam engines had evolved into high-pressure systems, thanks to engineers like Richard Trevithick. These compact, powerful machines drove the expansion of railways and steamships, knitting the world together through trade and travel. The steam turbine, invented by Sir Charles Parsons in 1884, took this technology further, replacing pistons with spinning blades to generate electricity—a design still central to power plants today.

How Steam Engines Work

The principle behind a steam engine is straightforward yet elegant:

- Boiler: Water is heated in a sealed vessel (the boiler) using a fuel source like coal, wood, oil, or biomass. This produces steam under pressure.

- Expansion: The high-pressure steam is directed into a cylinder (in reciprocating engines) or against turbine blades. In a piston-based engine, the steam pushes the piston, which is connected to a crankshaft or flywheel to produce rotary motion. In turbines, the steam spins the blades directly.

- Exhaust: After doing its work, the steam is released or condensed. In efficient designs, it’s returned as water to the boiler in a closed loop.

- Mechanical Output: The motion drives machinery—whether it’s a pump, a loom, or an electric generator.

Reciprocating steam engines, with their rhythmic chug, are the classic form, often seen in old locomotives. They use pistons moving back and forth, with valves controlling steam intake and exhaust. Steam turbines, by contrast, are smoother and more efficient, converting steam’s kinetic energy into continuous rotation, ideal for large-scale power generation.

Technical Details

- Pressure: Early engines operated at low pressure (below 15 psi), but modern designs can handle hundreds of psi, increasing power output.

- Efficiency: Watt’s condenser boosted efficiency from about 1% to 5%, while modern steam systems (especially turbines) can exceed 40% with superheated steam and advanced materials.

- Power: Output is measured in horsepower (hp) or kilowatts (kW). A small industrial steam engine might produce 10-50 hp, while a locomotive could exceed 1,000 hp.

Decline and Revival

By the early 20th century, steam engines faced competition from internal combustion engines (faster, more compact) and electric motors (cleaner, more efficient). Diesel locomotives replaced steam trains, and cars overtook steam-powered vehicles. Yet steam never fully disappeared. Steam turbines remain critical in power plants—coal, nuclear, and even solar thermal facilities rely on them to generate electricity. Meanwhile, reciprocating steam engines have found niche roles in historical preservation, education, and small-scale power generation.

EMS Power Machines and Modern Steam Engines

Enter EMS Power Machines, a company founded in 1961 that has grown into a global leader in power equipment. While they’re known for a broad portfolio—including diesel generators, electric motors, and pumps—steam engines are a key part of their offerings, reflecting their commitment to versatile, reliable power solutions.

EMS Steam Engine Features

EMS designs steam engines for industrial and specialized applications, blending traditional principles with modern engineering:

- Construction: Built with high-grade steel and alloys to withstand heat and pressure, ensuring longevity in harsh environments.

- Customization: EMS tailors engines to client needs, offering variations in size, power output, and fuel compatibility. A small engine might power a remote workshop, while a larger one could drive an industrial process.

- Fuel Flexibility: Their engines can use coal, biomass, or waste heat, appealing to industries seeking sustainable or cost-effective options.

- Applications: Beyond power generation, EMS steam engines might serve marine propulsion, historical replicas, or off-grid systems where electricity is scarce.

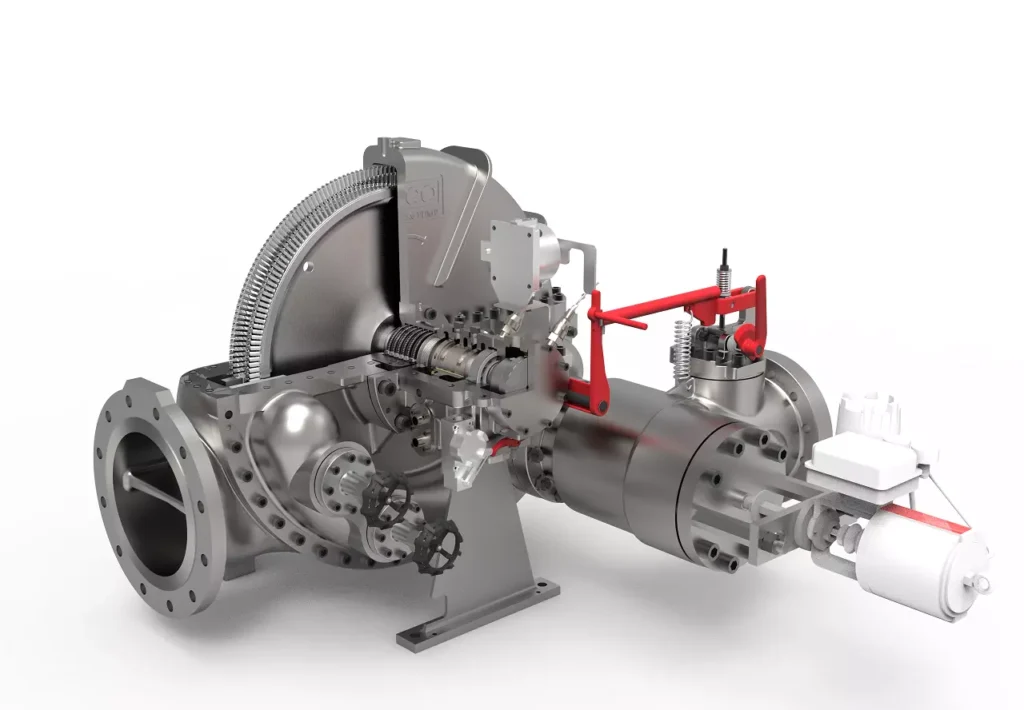

Comparison to Steam Turbines

EMS also manufactures steam turbines, which differ from their reciprocating engines. Turbines are more efficient for continuous, high-volume power generation—think megawatt-scale plants—while reciprocating engines suit smaller, intermittent tasks or mechanical drive systems. A factory might use an EMS steam engine to power a conveyor, while a turbine generates electricity for the grid.

Why Steam in 2025?

In an era of solar panels and lithium batteries, steam engines might seem archaic, but they have enduring strengths:

- Reliability: They operate in rugged conditions without complex electronics, ideal for remote or developing regions.

- Sustainability: Biomass or waste-heat-driven engines align with green energy trends.

- Heritage: EMS caters to clients preserving historical machinery or needing bespoke solutions.

EMS’s Place in the Market

With over 60 years of experience, EMS Power Machines stands out for its engineering pedigree. Their steam engines aren’t mass-market consumer goods but specialized tools for industries, governments, and enthusiasts. As one of the top five global leaders in installed power equipment, their steam offerings complement their broader mission of delivering robust, innovative power solutions worldwide.

The Broader Impact of Steam Engines

Steam engines didn’t just power machines—they reshaped society. They enabled mass production, urban growth, and global trade, but also brought challenges like pollution and labor upheaval. Today, their legacy lives on in turbines that light our homes and in companies like EMS that keep the technology alive.

The Engineering Marvel of Steam Engines: A Closer Look

Steam engines are deceptively simple yet endlessly complex when you peel back the layers. Their ability to turn heat into motion relies on a dance of physics—thermodynamics, pressure dynamics, and mechanical design—all working in harmony.

Anatomy of a Reciprocating Steam Engine

Picture a classic steam locomotive chugging along. Here’s what’s happening inside:

- Boiler: The heart of the system, where water becomes steam. Early boilers were riveted iron, prone to catastrophic explosions, but modern ones (like those from EMS) use welded steel, capable of handling pressures up to 300 psi or more. Superheaters—tubes that heat steam beyond its boiling point—boost efficiency by reducing condensation in the cylinder.

- Cylinder and Piston: Steam enters the cylinder through a valve, pushing the piston one way, then the other (in double-acting engines). The piston’s rod connects to a crosshead, then a connecting rod, and finally a crankshaft, turning linear motion into rotation. Precision machining ensures a tight seal, minimizing steam loss.

- Valve Gear: This is the brain, timing the steam’s entry and exit. The Stephenson valve gear, common in locomotives, uses an eccentric crank to slide valves back and forth. More advanced designs, like Walschaerts gear, offer finer control, a nod to the ingenuity of 19th-century engineers.

- Flywheel: A heavy wheel that smooths out the piston’s jerky motion, storing energy to keep the system running between strokes.

- Condenser: In efficient setups, exhausted steam is cooled back into water, reducing fuel use—a Watt innovation EMS likely incorporates in modern designs.

Steam Turbines: The Next Evolution

While EMS produces reciprocating engines, their steam turbines deserve a mention. Unlike pistons, turbines use rows of blades—some fixed, some rotating—arranged in stages. Steam rushes through, losing pressure and gaining speed, spinning the rotor at thousands of RPM. A single turbine might generate 1,000 horsepower or more, dwarfing most reciprocating engines. EMS turbines likely power industrial generators, tapping into the same principle that drives 80% of the world’s electricity today.

Efficiency and Challenges

Early steam engines converted just 1-2% of fuel energy into work—most heat was lost up the chimney. Watt’s condenser pushed this to 5%, and by the 1900s, triple-expansion engines (using steam in three stages) hit 20%. Modern steam systems, with superheated steam and insulation, can reach 40% or higher, though they still lag behind diesel (50%) or electric motors (90%). The trade-off? Steam’s simplicity and fuel flexibility outweigh efficiency concerns in certain niches.

Leaks, corrosion, and boiler maintenance remain hurdles. A burst boiler in the 1800s could level a building—today, EMS’s rigorous standards and materials like stainless steel mitigate such risks.

Steam Engines in History: Stories and Legends

Steam engines aren’t just machines; they’re characters in history’s drama.

- The Rocket: George Stephenson’s 1829 locomotive won the Rainhill Trials, proving steam could outpace horses. It hit 30 mph—a marvel then, quaint now—and sparked the railway boom.

- The Corliss Engine: At the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, a massive 1,400-hp engine by George Corliss awed crowds, powering miles of machinery via belts. It symbolized America’s industrial might.

- Titanic’s Engines: The ill-fated ship’s triple-expansion engines churned out 30,000 hp, a testament to steam’s peak before diesel took over maritime travel.

These machines weren’t flawless heroes. Boiler explosions killed thousands in the 19th century, prompting safety laws. Coal smoke choked cities, a grim side effect of progress. Yet steam also democratized power, freeing humanity from reliance on wind, water, or muscle.

EMS Power Machines: Steam in the 21st Century

EMS Power Machines, born in 1961 as a modest electric motor factory, now stands as a global titan in power equipment. Their steam engines bridge past and present, serving clients who need reliable, bespoke solutions.

What EMS Brings to Steam

- Craftsmanship: Each engine is a blend of traditional design and modern precision. Computer-aided design (CAD) ensures perfect tolerances, while durable alloys resist wear.

- Power Range: Small units might deliver 10-100 hp for workshops or farms, while larger ones could hit 500 hp for industrial tasks. Exact specs depend on customization—EMS’s hallmark.

- Fuel Innovation: Beyond coal, EMS engines can burn biomass (wood, agricultural waste) or tap waste heat from factories, aligning with sustainability goals. A biomass-fired engine might power a rural grid, cutting reliance on diesel.

- Niche Markets: Think heritage railways needing authentic replicas, or remote mines where electricity isn’t an option. EMS also caters to marine clients—steam-powered yachts or small vessels remain a quirky niche.

A Hypothetical EMS Engine

Imagine an EMS steam engine for a modern sawmill:

- Specs: 50 hp, 150 psi, double-acting cylinder, biomass boiler.

- Use: Drives a saw blade via belts, with exhaust steam heating the mill in winter.

- Cost: Likely $10,000-$50,000, depending on scale—affordable for industrial buyers, not hobbyists.

Why Steam Persists

Steam’s staying power lies in its ruggedness. No batteries to degrade, no electronics to fry—just metal, water, and fire. In a blackout, an EMS steam engine could keep a factory humming while solar panels sit idle. Developing nations, with abundant biomass but spotty grids, are prime customers.

Cultural Echoes and Future Prospects

Steam engines linger in our imagination—think steampunk novels or the Hogwarts Express. They evoke a tactile, clanking romance electric motors can’t match. Museums preserve them, enthusiasts restore them, and companies like EMS build them anew.

Looking ahead, steam could stage a quiet comeback. Concentrated solar power (CSP) uses mirrors to heat fluids, driving steam turbines. Geothermal plants do the same with Earth’s heat. EMS might adapt their engines for such systems, pairing old tech with new energy. Climate change pushes us toward carbon-neutral fuels—biomass-fed steam fits that bill.

Final Thoughts

Steam engines are a testament to human ingenuity, from Watt’s workshop to EMS’s factories. They’re not relics but living tools, adaptable to a world that’s never stopped needing power. Whether you’re drawn to their history, mechanics, or modern twists, they’re a story worth telling.

The Hidden Nuances of Steam Engines

Steam engines are more than pistons and boilers—they’re a symphony of subtle engineering choices and trade-offs that reveal the brilliance (and occasional madness) of their creators.

The Art of Steam Control

- Governors: Ever wonder how a steam engine doesn’t tear itself apart at high speed? Enter the centrifugal governor, a spinning pair of balls that rise with RPM, throttling steam intake to maintain steady output. James Watt popularized this in the 1780s, and EMS likely uses modern variants—perhaps electronic sensors—for precision.

- Cutoff: A clever trick in reciprocating engines is adjusting when steam stops entering the cylinder. Early cutoff lets steam expand longer, saving fuel but reducing power; late cutoff maximizes grunt at efficiency’s expense. Operators tweak this like a chef seasoning a stew—EMS engines might feature adjustable cutoffs for flexibility.

- Compounding: In compound engines, steam passes through multiple cylinders (high-pressure, then low-pressure) before exhausting. The “triple-expansion” design, a 19th-century marvel, squeezed every drop of energy from steam. EMS could offer compact compound engines for clients craving efficiency.

Boiler Dynamics

The boiler isn’t just a pot—it’s a pressure cooker with personality. Fire-tube boilers (hot gases pass through tubes in water) were locomotive staples, simple but limited in pressure. Water-tube boilers (water in tubes, surrounded by fire), favored in power plants, handle higher pressures—EMS likely uses these for industrial-grade engines. Superheating, where steam hits 400°C or more, dries it out, preventing cylinder damage and boosting output. A modern EMS boiler might pair with a digital control system, optimizing heat without the guesswork of a coal-shoveling fireman.

Materials Matter

Early engines used iron—cheap but brittle. Steel revolutionized steam in the late 1800s, and today, EMS might employ stainless steel or nickel alloys for corrosion resistance. Pistons and valves get special treatment—bronze or hardened steel—to endure steam’s relentless pounding. Lubrication’s a challenge too; high-temperature oils keep parts sliding smoothly, a detail EMS engineers surely obsess over.

Steam’s Global Footprint

Steam engines didn’t just power machines—they rewired the world’s economic and social fabric.

The Industrial Backbone

In Britain’s textile mills, steam drove spinning jennies and looms, turning cotton into wealth. By 1850, Manchester’s “Cottonopolis” hummed with thousands of steam horsepower, employing armies of workers—and kids, sadly—in grim conditions. Across the Atlantic, America’s steam-powered steamboats plied the Mississippi, hauling goods and people, while railways stitched a sprawling nation together. The transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869, owed its muscle to steam locomotives.

Colonial Engine

Steam was an imperial tool too. Britain’s steamships—like the Nemesis in the Opium Wars—dominated seas, enforcing trade and conquest. In India, railways built with British steam tech linked ports to plantations, funneling tea and spices to London. EMS’s global reach echoes this legacy, though now it’s about empowerment, not exploitation—supplying power to emerging economies.

War and Steam

Steam flexed its might in conflict. Civil War ironclads like the Monitor used steam to outmaneuver sail, while World War I dreadnoughts relied on steam turbines for speed. Even tanks, like the British Mark I, traced their lineage to steam’s mechanical principles. EMS’s industrial clients today might not build warships, but their engines could power factories supporting defense logistics.

EMS Power Machines: Innovating Steam

EMS, with its 60-year pedigree, doesn’t just preserve steam—it reimagines it. Let’s speculate on how they might push this tech forward in 2025.

Hypothetical EMS Innovations

- Hybrid Systems: Pair a steam engine with solar thermal panels. Mirrors focus sunlight to heat a boiler, driving an EMS engine by day, with biomass kicking in at night. A 100-hp unit could power a rural hospital—clean, reliable, and grid-independent.

- Micro Steam: Miniaturized engines (5-20 hp) for small businesses—think a coffee roaster or craft brewery. Compact boilers burn wood pellets, and a sleek design fits in tight spaces. EMS could market these as “heritage power with a modern twist.”

- Waste Heat Recovery: Factories bleed heat—EMS could design engines to capture it. A 200-hp engine might run off a steel mill’s exhaust, turning waste into work. It’s green tech with a steampunk vibe.

- Smart Steam: Integrate IoT sensors—monitor pressure, temperature, and wear in real time. An EMS app could alert operators to maintenance needs, cutting downtime. It’s Watt’s governor, but digital.

Manufacturing Edge

EMS’s plants likely hum with CNC machines carving precision parts, while engineers test prototypes under punishing conditions—say, 500 hours at full steam. Their global supply chain sources high-grade steel from Europe, electronics from Asia, and assembles it all with craftsmanship honed since ’61. Quality control? Rigorous—every engine ships with a pedigree, ensuring it won’t falter in a Siberian winter or Saharan heat.

Who’s Buying?

- Developing Nations: Places like rural Indonesia or sub-Saharan Africa, where grids are patchy but biomass is plentiful. An EMS engine powers a village mill or water pump.

- Enthusiasts: Steam buffs restoring a 1920s tractor or building a backyard locomotive. EMS offers custom kits—pricey, but prized.

- Industry: Mines, lumber yards, or food processors needing mechanical power without complex infrastructure. A 300-hp EMS engine might drive a conveyor belt in Peru’s Andes.

Steam’s Soul: Beyond the Machine

Steam engines have a visceral allure. The hiss of steam, the clank of metal, the smell of hot oil—it’s raw, alive. Films like The Polar Express or games like Frostpunk keep steam in our cultural bloodstream, a symbol of grit and ingenuity. EMS taps into this, selling not just machines but a connection to that legacy.

Environmental Angle

Coal-fired steam blackened skies, but today’s story is brighter. Biomass cuts carbon footprints—burning wood releases what trees already absorbed. Waste-heat engines emit nothing new. EMS could pitch steam as a bridge tech—sustainable until fusion or next-gen batteries mature.

What’s Next?

Steam’s future might surprise us. NASA once toyed with steam-powered Mars rovers, using radioactive decay to heat boilers—proof the concept scales beyond Earth. EMS might not go interplanetary, but they could eye geothermal niches or emergency power systems for climate-ravaged regions.

Wrapping the Steam Saga

From Newcomen’s clunky pump to EMS’s sleek engines, steam’s journey is a testament to adaptation. It’s powered revolutions, won wars, and still hums in corners of the world we overlook. EMS Power Machines carries that torch, proving steam’s not a fossil but a phoenix—reborn for new challenges.

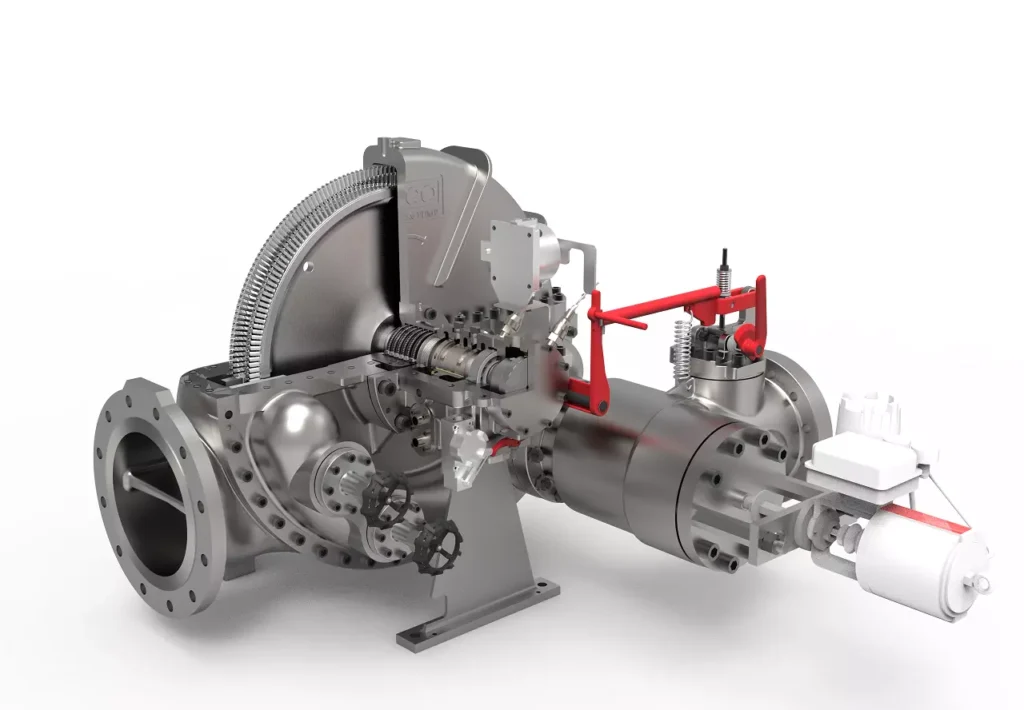

Steam Turbines

A steam turbine is a machine that converts the thermal energy of steam into mechanical energy. Steam turbines are used in a variety of applications, including generating electricity, driving compressors and pumps, and powering ships.

Steam turbines work by using the pressure of steam to push blades on a rotor. The rotor is connected to a shaft, which turns as the rotor spins. The shaft can then be used to power other machines.

Steam turbines are classified into two main types: reaction turbines and impulse turbines.

Reaction turbines use the expanding force of steam to move the rotor blades. Reaction turbines are typically used in applications where high efficiency is required.

Impulse turbines use the force of steam jets to move the rotor blades. Impulse turbines are typically used in applications where high power is required.

Steam turbines are an important part of our modern infrastructure. They are used to generate electricity, power ships, and drive a wide variety of industrial machines.

Here are some of the benefits of using steam turbines:

- Efficiency: Steam turbines are very efficient machines. They can convert a high percentage of the fuel’s energy into mechanical energy.

- Reliability: Steam turbines are very reliable machines. They can operate for long periods of time without any problems.

- Durability: Steam turbines are very durable machines. They can withstand harsh operating conditions.

- Scalability: Steam turbines can be built in a wide range of sizes, from small turbines for industrial use to large turbines for generating electricity. This makes them a versatile and adaptable technology.

Steam turbines play a vital role in the modern world. They provide us with the electricity we need to power our homes, businesses, and industries.

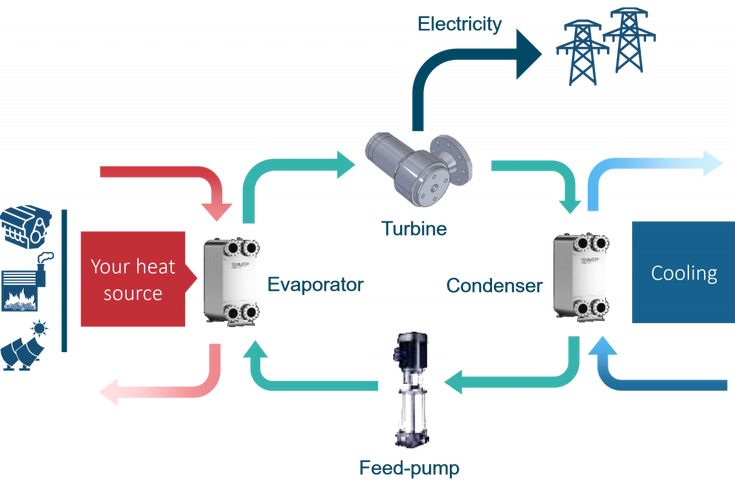

Steam turbines are one of the main sources of energy in the industry where there is a heat source and a demand for electricity.

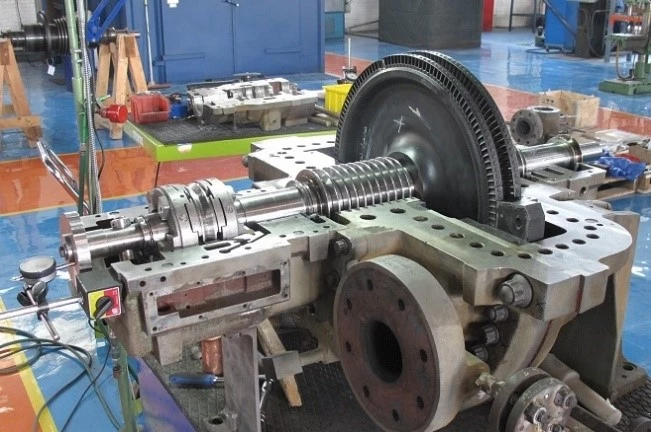

Small sized steam turbines are used in a variety of applications ranging from power generation in small-scale power plants to mechanical drives in industrial equipment. A steam turbine is a machine that converts thermal energy from steam into mechanical energy. Small sized steam turbines typically generate power in the range of a few kilowatts to several megawatts.

The design of small sized steam turbines typically involves several stages of blades that expand steam to create rotational force. The steam turbine rotor is typically mounted on bearings and rotates on a shaft. The steam is fed into the turbine through nozzles and directed onto the blades, causing the rotor to spin. The rotational force is transferred to a generator or other equipment to produce electricity or mechanical power.

Steam turbines are fascinating machines that have played a pivotal role in shaping the modern industrial landscape. They are mechanical devices designed to convert thermal energy from pressurized steam into rotational mechanical energy, which can then be used to generate electricity or drive machinery. The concept dates back to the late 19th century, with significant contributions from engineers like Sir Charles Parsons, who is credited with inventing the modern steam turbine in 1884. Since then, steam turbines have become a cornerstone of power generation, widely used in thermal power plants, including those fueled by coal, natural gas, nuclear energy, and even concentrated solar power.

The basic principle behind a steam turbine is relatively straightforward. High-pressure steam, produced by heating water in a boiler, is directed onto a series of blades mounted on a rotor. As the steam flows over these blades, it expands and accelerates, imparting its kinetic energy to the rotor and causing it to spin. This spinning motion is then harnessed—either directly to drive mechanical equipment or, more commonly, to turn a generator that produces electricity. The steam, having lost much of its energy, exits the turbine at a lower pressure and temperature, often to be condensed back into water and recycled through the system.

Steam turbines come in various designs, tailored to specific applications. The two primary categories are impulse turbines and reaction turbines. In an impulse turbine, the steam’s pressure drops as it passes through stationary nozzles, converting thermal energy into high-velocity jets that strike the rotor blades. Parsons’ original design was a reaction turbine, where the pressure drop occurs gradually across both stationary and moving blades, allowing for a more continuous transfer of energy. Modern turbines often combine elements of both designs, known as impulse-reaction turbines, to optimize efficiency and performance.

Efficiency is a critical factor in steam turbine design. Early models were relatively inefficient, converting only a small fraction of the steam’s energy into useful work. Advances in materials science, aerodynamics, and thermodynamics have dramatically improved this over time. Today’s steam turbines, especially those in large power plants, can achieve thermal efficiencies exceeding 40%, and when paired with combined-cycle systems (where waste heat is captured and reused), overall efficiencies can approach 60%. High-strength alloys and ceramics allow turbines to operate at higher temperatures and pressures, while precision engineering minimizes energy losses due to friction or leakage.

The scale of steam turbines varies widely. Small industrial units might produce a few kilowatts to power localized machinery, while the massive turbines in modern power stations can generate hundreds of megawatts—enough to supply electricity to entire cities. For example, a single turbine in a nuclear power plant might weigh hundreds of tons, with blades ranging from a few inches at the high-pressure end to several feet at the low-pressure exhaust, reflecting the steam’s expansion as it moves through the system.

Steam turbines have applications beyond electricity generation. In marine propulsion, they powered many of the great ships of the 20th century, from the RMS Titanic to naval warships, though they’ve largely been supplanted by diesel engines and gas turbines in modern fleets. In industrial settings, they drive pumps, compressors, and other heavy equipment, particularly in refineries and chemical plants where steam is already a byproduct of other processes.

Despite their age, steam turbines remain relevant in the push toward sustainable energy. They’re integral to geothermal power plants, where naturally occurring steam from the Earth’s crust is harnessed, and in biomass facilities that burn organic material to produce steam. Even in next-generation nuclear reactors, like small modular reactors (SMRs), steam turbines are the workhorses that turn heat into power.

Maintenance and longevity are key considerations. A well-maintained steam turbine can operate for decades, though it requires regular inspection to prevent issues like blade erosion (from water droplets in the steam) or fouling (from mineral deposits). Advances in digital monitoring and predictive maintenance have extended their lifespan and reliability, ensuring they remain a mainstay of global energy infrastructure.

In essence, the steam turbine is a testament to human ingenuity—a machine that took the simple act of boiling water and turned it into a driving force of the industrial age, and one that continues to adapt and thrive in an era of evolving energy demands.

Components and Design Details

A steam turbine is a complex assembly of precisely engineered parts, each serving a specific purpose. At its core is the rotor, a shaft lined with rows of blades (often called buckets in impulse designs). These blades are meticulously shaped—curved and angled to maximize the transfer of energy from the steam. The rotor sits within a casing, a robust enclosure that contains the steam and directs its flow. The casing is typically split into high-pressure, intermediate-pressure, and low-pressure sections, reflecting the steam’s journey as it loses energy.

The blades themselves are a marvel of engineering. In the high-pressure stages, they’re smaller and made from high-strength materials like stainless steel or titanium alloys to withstand extreme temperatures (often exceeding 500°C) and pressures (up to 200 bar or more). As the steam expands and cools in the low-pressure stages, the blades grow larger—sometimes over a meter long in massive power plant turbines—to extract energy from the lower-velocity flow. Blade design involves sophisticated aerodynamics, often drawing on principles similar to those used in jet engines, with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) now playing a major role in optimizing their profiles.

Between the moving rotor blades are stator blades (or nozzles), fixed to the casing. In impulse turbines, these nozzles accelerate the steam into high-speed jets, while in reaction turbines, they work in tandem with the rotor blades to create a continuous pressure drop. The alignment and spacing of these blade rows—known as stages—are critical. A large turbine might have dozens of stages, each extracting a fraction of the steam’s energy, a process that Sir Charles Parsons likened to “milking” the steam for all it’s worth.

The bearings supporting the rotor are another crucial element. Operating at speeds that can exceed 3,600 RPM (or 60 revolutions per second) in power plant turbines, the rotor needs to be perfectly balanced and lubricated to avoid vibration or wear. Modern turbines often use hydrodynamic or magnetic bearings, reducing friction and enabling high-speed, long-term operation.

Thermodynamic Cycle and Operation

Steam turbines operate within a thermodynamic cycle, most commonly the Rankine cycle, which governs how heat is converted into work. Water is heated in a boiler to produce superheated steam—steam heated beyond its boiling point to increase its energy content. This steam enters the turbine at high pressure and temperature, expands as it passes through the stages, and exits at a lower pressure and temperature. The exhaust steam is then condensed back into water in a condenser, often using cooling towers or a nearby water source, and pumped back to the boiler to repeat the cycle.

In practice, the Rankine cycle is enhanced with modifications like reheating and regeneration. In a reheat cycle, steam is partially expanded in the high-pressure turbine, sent back to the boiler to be reheated, and then returned to an intermediate or low-pressure turbine. This boosts efficiency by keeping the steam hotter for longer, reducing the risk of moisture forming in the later stages (wet steam can erode blades). Regeneration involves preheating the feedwater with steam extracted from intermediate stages, further improving efficiency by minimizing heat loss.

Efficiency and Performance Optimization

The efficiency of a steam turbine hinges on minimizing losses. One major loss is entropy increase, an inevitable consequence of thermodynamic processes, but engineers mitigate this through precise control of steam conditions. Superheating the steam, for instance, prevents condensation within the turbine, which not only protects the blades but also ensures more energy is available for work. The isentropic efficiency—a measure of how closely the turbine approaches an ideal, reversible process—can reach 90% or more in modern designs.

Another factor is the back pressure at the turbine’s exhaust. Lowering the pressure in the condenser (often to a near-vacuum, around 0.05 bar) maximizes the pressure drop across the turbine, extracting more energy. This is why power plants often have enormous cooling towers or are sited near rivers or oceans. In combined-cycle plants, steam turbines pair with gas turbines, using the latter’s hot exhaust to generate steam, pushing system efficiencies toward 60% or higher.

Materials and Manufacturing

The materials used in steam turbines are pushed to their limits. High-pressure sections require alloys that resist creep (slow deformation under heat and stress) and corrosion from steam impurities. Nickel-based superalloys, often used in jet engines, are common in advanced turbines, while chromium-molybdenum steels dominate in less extreme conditions. Blades may be coated with ceramic thermal barriers or anti-corrosion layers. Manufacturing involves precision casting, forging, and machining, with tolerances measured in microns to ensure perfect alignment and balance.

Challenges and Maintenance

Steam turbines face operational challenges like blade fatigue, caused by cyclic stresses, and erosion from water droplets in wet steam. Vibration, if unchecked, can lead to catastrophic failure, so turbines are equipped with sensors to monitor rotor dynamics. Maintenance involves shutting down the turbine—a costly process in power plants—so predictive analytics and non-destructive testing (like ultrasonic scans) are increasingly used to spot issues early.

Variants and Specialized Applications

Beyond standard designs, there are specialized steam turbines. Back-pressure turbines exhaust steam at above-atmospheric pressure for industrial heating, common in cogeneration plants. Extraction turbines bleed off steam at intermediate pressures for processes like desalination or district heating. In nuclear plants, turbines are often larger and slower (1,500–1,800 RPM) to handle the lower-temperature steam from reactors, requiring massive low-pressure stages.

Future Innovations

Looking ahead, steam turbines are evolving. Supercritical and ultra-supercritical steam cycles operate at extreme pressures (above 221 bar) and temperatures (up to 600°C or more), pushing efficiencies further. Research into carbon capture integration and hydrogen-fired boilers could keep steam turbines relevant in a decarbonized world. Meanwhile, digital twins—virtual models updated in real-time—optimize performance and maintenance.

In short, steam turbines are a blend of brute force and delicate precision, a technology refined over a century yet still adapting to new challenges. Their story is one of relentless improvement, turning the humble power of steam into a linchpin of modern civilization.

Advanced Engineering Features

One of the most intricate aspects of steam turbine design is the staging process. Multi-stage turbines, common in power generation, can have dozens or even hundreds of blade rows, divided into high-pressure (HP), intermediate-pressure (IP), and low-pressure (LP) sections. Each stage is tailored to the steam’s changing properties as it expands. In the HP section, steam is dense and energetic, requiring small, robust blades. By the LP section, the steam’s volume has increased dramatically—sometimes by a factor of 1,000—necessitating huge blades to capture its remaining energy. This progression is governed by the velocity compounding or pressure compounding principles in impulse turbines, where energy is extracted in discrete steps, or the smoother energy transfer of reaction turbines.

The nozzle design in impulse turbines is another critical detail. These stationary components accelerate steam to supersonic speeds, often exceeding Mach 1, creating shockwaves that must be carefully managed to avoid energy losses. Converging-diverging nozzles, based on the de Laval principle, are used to achieve this, with the narrow “throat” choking the flow to sonic speed before the diverging section accelerates it further. In reaction turbines, the stator and rotor blades form a continuous series of miniature nozzles, a design that demands precise machining to maintain efficiency.

Sealing is a less glamorous but vital feature. Steam leakage between stages or around the rotor shaft wastes energy and reduces output. Labyrinth seals—complex, maze-like pathways—force steam to lose pressure as it tries to escape, while carbon or brush seals provide tighter closure in high-performance units. In supercritical turbines, where pressures are extreme, sealing becomes even more challenging, often requiring advanced materials like Inconel or ceramic composites.

Historical Evolution

The steam turbine’s journey began before Parsons, with rudimentary designs like Hero of Alexandria’s aeolipile (a steam-powered spinning sphere) in the 1st century AD. However, practical applications emerged in the 19th century. Gustaf de Laval’s 1883 impulse turbine, designed for high-speed cream separators, introduced the concept of supersonic steam jets. Parsons’ 1884 reaction turbine, though, was the game-changer, powering a 7.5 kW generator and later the Turbinia, a ship that stunned onlookers at the 1897 Spithead Naval Review by outrunning every vessel present.

Early turbines were limited by materials—cast iron and basic steels couldn’t handle high temperatures or stresses. The 20th century brought alloy steels, then superalloys, enabling turbines to scale up. By the 1920s, turbines were powering cities, with units like those in the Battersea Power Station in London producing tens of megawatts. World War II accelerated development, as naval turbines demanded compact, high-power designs. Post-war, the nuclear age brought massive, low-speed turbines optimized for the saturated steam of early reactors.

Specific Applications in Depth

In nuclear power, steam turbines face unique challenges. Unlike fossil-fuel plants, where steam is superheated, nuclear reactors often produce wet or saturated steam at lower temperatures (around 280–300°C). This requires larger LP stages to handle the higher moisture content and prevent blade erosion. Moisture separators and reheaters are often integrated mid-cycle to dry the steam, a complexity not needed in coal or gas plants. A typical nuclear turbine might produce 1,000 MW, with a rotor spanning 20 meters and weighing 300 tons.

In geothermal plants, turbines deal with steam from natural reservoirs, often laden with corrosive gases like hydrogen sulfide. Specialized coatings and materials, like titanium or hastelloy, protect against this, while the lower pressures (5–20 bar) compared to fossil plants require different blade profiles. Iceland’s Hellisheiði plant, for instance, uses steam turbines to tap volcanic heat, generating both electricity and hot water for Reykjavik.

Marine turbines, though less common today, were engineering feats. The Queen Mary’s turbines delivered 160,000 shaft horsepower, driving four propellers via reduction gears (since turbines spin too fast for direct propulsion). These systems included reversing stages—small turbine sections that spun backward for maneuvering—adding complexity to an already intricate machine.

Cutting-Edge Developments

Modern steam turbine research focuses on efficiency, sustainability, and adaptability. Supercritical and ultra-supercritical (USC) turbines operate above water’s critical point (221 bar, 374°C), where it transitions seamlessly between liquid and gas. USC conditions—up to 300 bar and 620°C—demand exotic materials and push efficiencies toward 50%. General Electric’s H-class turbines, for example, pair USC steam cycles with gas turbines for record-breaking performance.

In the renewable realm, concentrated solar power (CSP) uses steam turbines driven by solar-heated steam. Plants like Nevada’s Crescent Dunes use molten salt to store heat, running turbines overnight. These systems often incorporate smaller, modular turbines (10–100 MW) optimized for variable steam supply.

Hydrogen integration is another frontier. Burning hydrogen in boilers to produce steam could decarbonize turbine-based power, though it requires rethinking combustion systems and steam chemistry. Meanwhile, advanced manufacturing—like 3D printing of turbine blades—allows for complex geometries that reduce weight and improve airflow, while digital twins use AI to predict wear and optimize operation in real time.

Operational Nuances

Turbine startup and shutdown are delicate processes. Rapid heating or cooling can cause thermal stress, cracking blades or casings, so operators use gradual warm-up cycles, sometimes lasting hours. Load following—adjusting output to match demand—is trickier with steam turbines than gas turbines, but modern designs with variable nozzles or bypass systems improve flexibility.

Noise and vibration are ever-present concerns. A large turbine at full speed generates a deafening roar, requiring soundproofing in plants near populated areas. Vibration analysis, using accelerometers and laser alignment, ensures the rotor stays balanced, as even a slight wobble can shear blades or bearings.

Cultural and Economic Impact

Steam turbines have shaped economies and societies. They powered the electrification of the world, from Edison’s Pearl Street Station to today’s grids. Their reliability—some units run for 50+ years—makes them economic linchpins, though their capital cost (millions for a large unit) and long build times challenge new projects in a fast-moving energy market.

In summary, steam turbines are a symphony of physics, metallurgy, and precision, evolving from Victorian ingenuity to high-tech workhorses. Their adaptability ensures they’ll remain relevant, whether spinning under fossil steam or the heat of a sustainable future.

Types of Steam Turbines

There are two main types of steam turbines: impulse turbines and reaction turbines.

Impulse turbines

Impulse turbines use the force of steam jets to move the rotor blades. The steam jets are directed from nozzles onto the blades, which causes the blades to spin. Impulse turbines are typically used in applications where high power is required, such as in power plants and marine propulsion.

Reaction turbines

Reaction turbines use the expanding force of steam to move the rotor blades. The steam expands as it passes through the turbine, which causes the blades to spin. Reaction turbines are typically used in applications where high efficiency is required, such as in combined cycle power plants and industrial applications.

In addition to these two main types, there are a number of other types of steam turbines that are used in specialized applications. These include:

- Back-pressure turbines: Back-pressure turbines are used to generate electricity and provide steam for process heating or other industrial applications.

- Extraction turbines: Extraction turbines are used to generate electricity and extract steam at different pressures for process heating or other industrial applications.

- Condensing turbines: Condensing turbines are used to generate electricity and condense the steam to a liquid state.

- Reheat turbines: Reheat turbines are used to generate electricity by reheating the steam between stages of the turbine.

Steam turbines are an essential part of our modern infrastructure. They are used to generate electricity, power ships, and drive a wide variety of industrial machines. Steam turbines are also used in a number of other applications, such as desalination and district heating.

Here are some examples of steam turbine applications:

- Electricity generation: Steam turbines are used to generate electricity in thermal power plants, combined cycle power plants, and nuclear power plants.

- Marine propulsion: Steam turbines are used to power ships and submarines.

- Industrial applications: Steam turbines are used to drive compressors, pumps, and other machinery in a variety of industries, such as oil and gas, petrochemicals, and papermaking.

- Desalination: Steam turbines are used to power desalination plants, which convert seawater into freshwater.

- District heating: Steam turbines are used to generate heat for district heating systems, which provide heat to homes and businesses in a surrounding area.

Steam turbines play a vital role in the modern world. They provide us with the electricity, power, and heat that we need to power our homes, businesses, and industries.

Steam turbines are remarkable machines that convert thermal energy from steam into mechanical work, widely used in power generation, industrial processes, and propulsion systems. They operate on the principle of expanding high-pressure steam through a series of blades, causing rotation that can drive generators or other machinery. Over time, engineers have developed various types of steam turbines, each designed to optimize efficiency, performance, and application-specific requirements. Below is an exploration of the primary types of steam turbines, their configurations, and their uses.

1. Impulse Turbines

Impulse turbines operate based on the impulse principle, where high-pressure steam is directed through nozzles to form high-velocity jets that strike the turbine blades. The kinetic energy of the steam is transferred to the blades, causing the rotor to spin. In this design, the pressure drop occurs entirely in the nozzles, and the blades experience no significant pressure change as the steam passes through. A classic example of an impulse turbine is the De Laval turbine, which features a single stage and is known for its simplicity and high rotational speeds. Another well-known design is the Curtis turbine, which uses multiple stages of moving and stationary blades to extract energy more efficiently in a compact form.

Impulse turbines are often used in small-scale power generation or as the high-pressure stages in larger systems. Their advantages include simplicity and the ability to handle high-pressure steam effectively, though they may be less efficient at lower speeds or with variable loads.

2. Reaction Turbines

In contrast to impulse turbines, reaction turbines rely on both pressure drop and steam expansion across the turbine blades themselves. As steam passes through the moving blades, it accelerates and expands, creating a reactive force (similar to how a rocket works) that drives the rotor. This design was pioneered by Sir Charles Parsons, and the Parsons turbine remains a foundational example. Reaction turbines typically feature multiple stages, with alternating rows of fixed (stator) and moving (rotor) blades, allowing for gradual energy extraction and higher efficiency.

Reaction turbines are widely used in large power plants because they excel at handling lower-pressure steam and can achieve greater efficiency over a range of operating conditions. However, they are more complex and costly to manufacture due to the precision required in blade design and staging.

3. Combination (Impulse-Reaction) Turbines

Many modern steam turbines combine impulse and reaction principles to optimize performance across different pressure ranges. For example, the high-pressure stages might use an impulse design to handle the initial steam conditions, while the low-pressure stages transition to a reaction design for better efficiency as the steam expands. This hybrid approach allows turbines to adapt to a wide variety of operating conditions, making them common in large-scale electricity generation plants.

4. Back-Pressure Turbines

Back-pressure turbines exhaust steam at a pressure higher than atmospheric pressure, allowing the exhaust steam to be used for industrial processes like heating, drying, or driving other machinery. These turbines are often found in cogeneration systems, where both electricity and heat are needed, such as in paper mills, chemical plants, or district heating systems. While they sacrifice some efficiency in power generation compared to condensing turbines, their ability to provide dual outputs makes them highly economical in specific applications.

5. Condensing Turbines

Condensing turbines are designed to maximize power output by exhausting steam into a vacuum, typically created by a condenser. This lowers the back pressure, allowing the steam to expand further and extract more energy. These turbines are the backbone of most large-scale power plants, including coal, nuclear, and combined-cycle gas plants. Their high efficiency comes at the cost of requiring a cooling system (often water-based), which adds complexity and environmental considerations.

6. Extraction Turbines

Extraction turbines are a versatile subtype that allow steam to be “extracted” at intermediate pressures from various stages of the turbine. This extracted steam can be used for industrial processes or heating, while the remaining steam continues through the turbine to generate power. These turbines are common in facilities needing both electricity and steam at different pressure levels, offering flexibility and efficiency in combined heat and power (CHP) systems.

7. Reheat Turbines

Reheat turbines improve efficiency by incorporating a reheat cycle. After passing through the high-pressure stages, steam is sent back to the boiler to be reheated before entering the intermediate- or low-pressure stages. This process increases the average temperature at which heat is added, boosting the turbine’s thermodynamic efficiency. Reheat designs are standard in large, high-efficiency power plants, though they require additional equipment and control systems.

8. Low-Pressure, Intermediate-Pressure, and High-Pressure Turbines

In large power plants, steam turbines are often divided into separate sections based on steam pressure: high-pressure (HP), intermediate-pressure (IP), and low-pressure (LP) turbines. These sections are typically mounted on a single shaft and work together to extract energy as the steam expands from high to low pressure. Each section is optimized for its specific pressure range, with blade sizes and designs varying accordingly—HP turbines have smaller, robust blades, while LP turbines have larger blades to handle the expanded, lower-pressure steam.

9. Single-Stage vs. Multi-Stage Turbines

Steam turbines can also be classified by the number of stages. Single-stage turbines, like the De Laval design, are simple and compact, suitable for small-scale or high-speed applications. Multi-stage turbines, such as those used in power plants, consist of multiple sets of blades, allowing for gradual energy extraction and higher efficiency. Multi-stage designs dominate in large-scale applications due to their ability to handle large steam volumes and pressure drops.

Applications and Considerations

Each type of steam turbine serves a specific purpose. Impulse turbines might power small generators or pumps, while reaction turbines drive massive gigawatt-scale power stations. The choice of turbine type depends on factors like steam conditions (pressure, temperature, and flow rate), desired output (power, heat, or both), and operational constraints (space, cost, and maintenance). Let’s dive deeper into each type with additional details on their design, mechanics, and real-world applications.

1. Impulse Turbines

Impulse turbines rely on the conversion of steam’s potential energy into kinetic energy before it interacts with the blades. The steam is accelerated through stationary nozzles, which are precisely shaped (often converging-diverging nozzles) to achieve supersonic velocities. When this high-speed jet hits the turbine’s bucket-shaped blades, the momentum transfer causes rotation. The blades are symmetrically designed to minimize axial thrust, and the steam exits at roughly the same pressure it entered, having lost much of its kinetic energy.

- De Laval Turbine: Invented by Gustaf de Laval in the late 19th century, this single-stage turbine was revolutionary for its time. It’s compact, with a single row of blades, and can reach speeds exceeding 30,000 RPM, making it ideal for driving high-speed machinery like centrifugal pumps or small generators. However, its efficiency drops with varying loads, limiting its use to niche applications.

- Curtis Turbine: Developed by Charles G. Curtis, this design adds a velocity-compounding feature. Steam passes through multiple rows of moving blades interspersed with stationary blades that redirect the flow. This staged approach reduces the rotor speed (compared to De Laval) while extracting more energy, making it suitable for early electrical generation systems.

- Applications: Impulse turbines shine in high-pressure, low-flow scenarios, such as topping turbines in combined-cycle plants or standalone units in remote locations. They’re less common in modern large-scale power generation due to efficiency limitations but remain critical in specialized industrial setups.

2. Reaction Turbines

Reaction turbines operate on a different principle: the blades act as nozzles themselves, accelerating and expanding the steam as it flows through. This creates a drop in pressure across each stage, generating a reactive force that drives the rotor. The stator blades (fixed) direct steam onto the rotor blades (moving), and the process repeats across multiple stages. The degree of reaction—typically around 50% in a Parsons turbine—refers to the proportion of energy extracted via reaction versus impulse.

- Parsons Turbine: Sir Charles Parsons’ 1884 invention introduced the multi-stage reaction concept, a breakthrough that transformed power generation. His turbines feature dozens or even hundreds of stages, with blade heights increasing as steam expands. This gradual energy extraction maximizes efficiency, especially at lower pressures.

- Design Nuances: Reaction turbine blades are airfoil-shaped, requiring precise manufacturing to handle aerodynamic forces and steam expansion. The rotor and stator blades are often paired in a 1:1 ratio, creating a balanced, continuous flow. Axial thrust is a challenge, necessitating thrust bearings to stabilize the rotor.

- Applications: Reaction turbines dominate in large fossil-fuel, nuclear, and geothermal power plants due to their scalability and efficiency at handling high steam volumes. They’re less suited to small-scale or high-pressure-only applications, where impulse designs may outperform.

3. Combination (Impulse-Reaction) Turbines

Combination turbines blend the strengths of both designs. The high-pressure section often uses impulse stages to manage the intense initial conditions (e.g., 200 bar, 540°C), where nozzles and robust blades excel. As steam pressure drops, the turbine transitions to reaction stages, leveraging expansion for efficiency in the intermediate- and low-pressure zones. This hybrid layout is tailored to the steam cycle’s thermodynamic profile.

- Mechanics: The transition between impulse and reaction stages is seamless, with blade designs and staging adjusted to match pressure gradients. For example, early stages might feature pure impulse (100% pressure drop in nozzles), while later stages approach 50% reaction.

- Advantages: This design optimizes efficiency across a wide pressure range, reduces mechanical stress, and allows for compact yet powerful turbines. It’s a staple in modern supercritical and ultra-supercritical coal plants, where steam conditions push material limits.

- Applications: Found in utility-scale power generation, especially where efficiency and output must be maximized, such as in combined-cycle plants integrating gas and steam turbines.

4. Back-Pressure Turbines

Back-pressure turbines exhaust steam at a usable pressure (e.g., 5-20 bar) rather than condensing it into a vacuum. The exhaust steam retains significant thermal energy, making it ideal for downstream processes. These turbines often operate in a non-condensing mode, with exhaust piped directly to industrial systems.

- Design Details: Simpler than condensing turbines, they lack a condenser and cooling system, reducing capital costs. Blade staging is optimized for a specific exhaust pressure, balancing power output with steam quality for process use.

- Efficiency Trade-Off: Electrical efficiency is lower than condensing turbines (since less energy is extracted), but total energy efficiency soars when process heat is factored in—sometimes exceeding 80% in cogeneration setups.

- Applications: Common in industries like pulp and paper (for drying), sugar refining (for evaporation), and petrochemical plants (for heating). They’re also used in district heating systems, where exhaust steam warms buildings.

5. Condensing Turbines

Condensing turbines push efficiency to the limit by exhausting steam into a vacuum (e.g., 0.05 bar), created by a condenser cooled with water or air. This maximizes the pressure drop across the turbine, extracting nearly all available energy from the steam.

- Mechanics: The low-pressure stages feature massive blades—sometimes over a meter long—to handle the high-volume, low-density steam. Condensers require significant infrastructure, including cooling towers or river/ocean water systems, adding complexity.

- Materials and Challenges: LP blades face erosion from wet steam (containing water droplets), necessitating alloys like titanium or protective coatings. Vacuum maintenance is critical, as leaks reduce efficiency.

- Applications: The backbone of baseload power plants—coal, nuclear, and gas-fired—where maximum electrical output is the goal. They’re less practical in small-scale or heat-focused systems due to their reliance on cooling.

6. Extraction Turbines

Extraction turbines offer flexibility by allowing steam to be tapped at intermediate points. Valves control the extraction process, diverting steam at specific pressures (e.g., 10 bar for heating, 2 bar for feedwater preheating) while the rest continues to the condenser.

- Design Complexity: Multiple extraction points require sophisticated control systems and additional piping. Blade staging must account for variable flow rates, as extraction reduces steam volume in later stages.

- Benefits: They balance power and heat output, adapting to fluctuating demands. Efficiency remains high when extraction is optimized with process needs.

- Applications: Prevalent in refineries, steel mills, and CHP plants, where steam serves dual purposes—electricity for operations and heat for processes like distillation or drying.

7. Reheat Turbines

Reheat turbines enhance efficiency by interrupting the expansion process. After the HP stages, steam (now at reduced pressure and temperature) returns to the boiler for reheating (e.g., back to 540°C), then re-enters the IP and LP stages. This raises the cycle’s average heat-addition temperature, a key thermodynamic advantage.

- Mechanics: Reheat requires additional piping, valves, and boiler capacity. Double-reheat systems (two reheats) push efficiency further but increase costs. LP stages must handle wetter steam post-reheat, requiring moisture separators.

- Efficiency Gains: Single reheat boosts efficiency by 4-5%, while double reheat adds another 2-3%, making them viable in ultra-efficient plants (e.g., 45%+ thermal efficiency).

- Applications: Standard in modern fossil-fuel plants, especially supercritical designs, and some nuclear plants with high steam output.

8. Low-Pressure, Intermediate-Pressure, and High-Pressure Turbines

In large systems, turbines are segmented into HP, IP, and LP units, often on a single shaft. Each section is a mini-turbine tailored to its steam conditions:

- HP Turbine: Small, robust blades handle ultra-high pressures (up to 300 bar) and temperatures (600°C+). Materials like chromium-steel alloys resist creep and corrosion.

- IP Turbine: Mid-sized blades manage reheated steam (20-50 bar), balancing strength and flow capacity.

- LP Turbine: Large blades (up to 1.5 meters) process low-pressure, high-volume steam, often in twin-flow designs to split the exhaust load.

- Applications: Universal in utility-scale plants, where modularity simplifies maintenance and optimization.

9. Single-Stage vs. Multi-Stage Turbines

- Single-Stage: Compact, with one set of blades, they’re fast and simple but inefficient for large power outputs. Used in small pumps, fans, or emergency generators.

- Multi-Stage: Multiple blade rows extract energy gradually, ideal for high-power applications. Complexity increases, but so does efficiency—up to 90% of available energy in modern designs.

Closing Thoughts

Steam turbines are marvels of engineering, with each type fine-tuned to its role. From the brute simplicity of a De Laval impulse turbine to the intricate staging of a reheat reaction turbine, their diversity reflects the ingenuity behind harnessing steam’s power. Whether driving a factory or lighting a city, these machines remain central to our energy landscape, evolving with advances in materials, controls, and thermodynamics.

The impulse turbine’s elegance lies in its straightforward energy transfer: steam’s kinetic energy is the sole driver. The nozzles are critical—they’re often made of high-strength alloys like stainless steel or Inconel to withstand erosion from high-velocity steam, especially if it carries moisture or particulates. Blade design is equally vital; the “buckets” are typically curved and polished to minimize friction losses, with precise angles to maximize momentum transfer.

- Historical Context: Gustaf de Laval’s 1880s design was a leap forward during the Second Industrial Revolution, enabling high-speed machinery when electricity was still emerging. His turbines powered early cream separators (a key invention of his), showcasing their versatility beyond power generation.

- Velocity Compounding (Curtis): In a Curtis turbine, steam ricochets between moving and stationary blades multiple times within a stage. This reduces the rotor speed to manageable levels (e.g., 3,000-6,000 RPM) for coupling with generators, avoiding the need for gearboxes—a common requirement with De Laval’s ultra-fast designs.